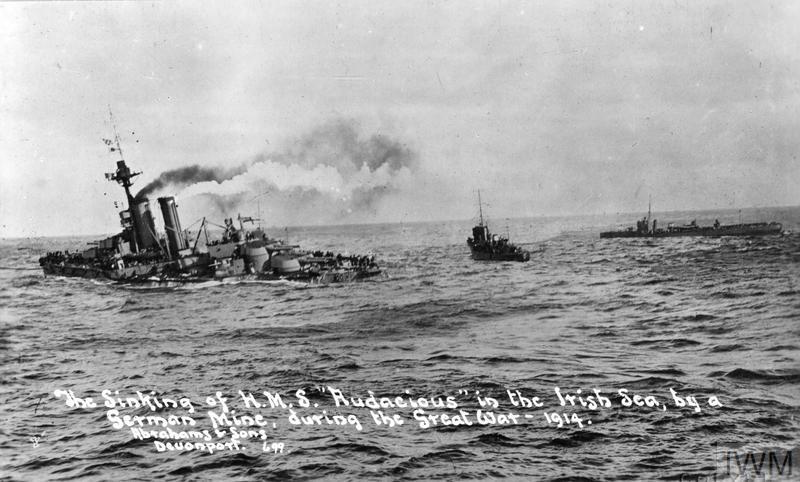

When war was declared on Germany on 3 September 1939 Britain immediately began to mobilise its forces. Whilst the bulk of the Royal Navy was focused on convoy protection and controlling the North Sea the Royal Navy Patrol Service (RNPS), comprised reservists from both the Royal Navy Reserve (RNR) and Royal Navy Volunteer Reserve (RNVR), was, among other duties, tasked with keeping Britain’s coastlines free from mines.[1] This it had done during the First World War, when German mines had caused considerable damage to the Royal Navy along Britain’s coastline. The most significant mining incidents were the sinking of the battleship HMS Audacious in the Irish Sea in 1914, and the cruiser HMS Hampshire, which notably was carrying British Army Field Marshal Lord Kitchener, off the Orkney Islands in 1916. Access points to the Atlantic Ocean, where the majority of Britain’s supplies had to cross, were through the English Channel and the North Sea. The German navy, therefore, were keen to establish dominance over these coastal waters to allow for the safe passage of its U-Boats and surface raiders. Thus, the defence of Britain’s coastal regions were of paramount importance to protection of the merchant convoys and the supplies they brought.

The RNPS had maintained a fleet of trawlers, coasters, and drifters during the interwar years, all capable of taking on the bulk of coastal minesweeping. Thus, when war broke out in 1939, the volunteers and reservists who sailed on these boats in peacetime were given an active or reservist officer and tasked with sweeping mines along the length of the British coastline. The nature of their service, and the fact that some of the requisitioned trawlers had been used as fishing trawlers, earned them the somewhat affectionate nickname ‘Harry Tate’s Navy’ after a comedian of the day noted for his aversion to modern technologies.[2]

However, the Second World War presented a problem that the British were not wholly expecting. Unbeknownst to the British at the time, the Kriegsmarine were using, magnetic mines. These ‘influence’ mines were different from the ‘contact’ mines that the Royal Navy was equipped and prepared to face as they did not require direct contact for actuation. Instead, the magnetic interference caused by the ferrous metals found on a ship passing overhead would actuate the mine. This presented two problems; firstly, since the mine did not require contact in order to actuate, it could be laid along or closer to the sea-floor in shallower waters, making it more difficult to sweep. Secondly, although the staff at the Royal Navy mine department at HMS Vernon in Portsmouth had been working on countermeasures even before the war had started, as they didn’t know the exact specifications of the German mines, they could not develop an effective countermeasure.[3]

Larger type of the early German magnetic mine, recovered in 1939, with rule alongside to show its size. © IWM A 30292.

The effectiveness of the magnetic mine campaign cannot be understated. The rivers along the east coast of Britain were particularly affected, for example the cruiser HMS Belfast was mined passing through the Firth of Forth on 21 November 1939, requiring nearly three years of repairs in dry dock. Similarly, HMS Nelson, the flagship of the Home Fleet, was damaged while it was anchored at Loch Ewe in the Scottish Highlands on 4 December 1939. In addition to this the minelaying cruiser HMS Adventure, along with one of its escorting destroyers, were damaged near Harwich – an area where a number of Royal Navy destroyers were also damaged during the period. The mining along the Thames Estuary was also relentless, with a number of neutral merchant vessels being sunk trying to navigate the river. With every report of mines in the shipping lanes, all traffic was stopped or redirected until the RNPS had completed sweeping in the area[4]

Despite the tireless efforts of Britain’s reservist minesweepers, Britain’s east coast ports were spared from total lockdown in the opening months of the war, thanks only to the fact that the German Kriegsmarine did not have enough mines or minelayers to capitalise on their technological advantage. In Germany both the Kriegsmarine and Luftwaffe debated how to proceed with its mining campaign. The Kriegsmarine wanted to begin using aircraft to sow minefields immediately and cause as much damage to Britain and its navy as soon as possible, at the risk of their ‘secret’ weapon being discovered. The Luftwaffe, however, preferred to wait until a sufficient stockpile could be procured so that they could be laid in one magnificent effort, overwhelming the Royal Navy minesweeping units. Ultimately, however, the Kriegsmarine began aerially laying minefields on 18 November 1939 without the assistance of the Luftwaffe.[5]

King George VI inspecting Ouvry’s mine at HMS VERNON on 19 December 1939. Found at https://www.vernon-monument.org.uk/history by courtesy of Rob Hoole.

On 23 November a Kriegsmarine aircraft dropped its payload of magnetic mines too close to the shore at Shoeburyness, near Southend-on-Sea and close to the mouth of the Thames estuary. Lieutenant Commander John Ouvry, the lead developer of Britain’s own non-contact mines, was sent along with Lieutenant Commander Roger Lewis and two ratings to the site where they proceeded to recover and render safe the discovered mine (a second mine was later discovered while the party were attending to the first). Once rendered safe, Ouvry and the mine were sent back to HMS Vernon where it’s secrets were unlocked. In the meantime Lewis was sent to Whitehall where he briefed the First Sea Lord, Winston Churchill, and King George VI.[6]

As a result of this recovery, the staff at HMS Vernon were able to produce a series of countermeasures such as the LL magnetic sweep which replaced the previous methods of magnetic sweeping and would remain effective throughout the war. The LL sweep consisted of a minesweeper towing two cables behind it, pulsing an electric current in order to mimic the passing of a ship and actuate any mines without presenting too much danger to the sweepers. In addition to sweeping, two methods of degaussing were implemented. Named after the noted physicist Carl Friedrich Gauss, the first method included installing an electric coil around the length of a ship in order to reverse its polarity. This proved to be an expensive solution, and so the process of ‘wiping’ a ship, where the magnetic signature was removed at port, was adopted instead. Both methods would make a ship’s hull effectively invisible to magnetic mines, and by the end of 1940, over 1700 warships and 2000 merchant navy ships would benefit from this research. Furthermore, the development of smaller, modular craft such as the wooden Fairmile B Motor Launch, able to be fitted as shallow-draught minesweepers, would prove to be extremely effective at sweeping coastal areas.[7]

Although the magnetic mine’s secrets had been discovered, it still proved to be an effective weapon throughout the war, as would the vast array of ‘influence mines’ that the Royal Navy would have to counter over the course of the war.[8] It is interesting to me that the throughout the war, the Kriegsmarine wished to wage its war against Britain itself as opposed to the Royal Navy. Since the Kriegsmarine did not have enough capital ships to challenge the Royal Navy, as it had in the First World War, it could not hope to achieve control of the North Sea. Control of the sea being perhaps the most important factor to a successful conflict according to the noted naval theorist Alfred Thayer Mahan.[9] Instead, the Kriegsmarine’s focus lay solely on attacking Britain’s shipping, both in the Atlantic and along Britain’s eastern coastline. Although my own research focus on mine warfare will take me to the latter stages of the Second World War, the efforts of Royal Navy professional and reservists alike in maintaining Britain’s coastline were instrumental for the defence and supply of Britain, during its ‘Darkest Hour’.

Notes

[1] Nick Hewitt, Coastal Convoys, 1939-1945: The Indestructible Highway (Barnsley: Pen & Sword Maritime, 2019), 34-39.

[2] Paul Lund and Harry Ludlam, Trawlers Go to War (London: New English Library Ltd. 1974), 10.

[3] Commander David Bruhn USN (Ret.) and Lieutenant Commander Rob Hoole RN., Enemy Waters: Royal Navy, Royal Canadian Navy, Royal Norwegian Navy, U.S. Navy and Other Allied Mine Forces Battling the Germans and Italians in World War II (Maryland: Heritage Books, 2019), 37-48.

[4] Julian Paul Foynes, The Battle of the East Coast (1939-1945) (Middlesex: J. P. Foynes, 1994), 1-34.

[5] David C. Isby (ed.), The Luftwaffe and the War at Sea 1939-1945: As seen by officers of the Kriegsmarine and Luftwaffe (London: Chatham Publishing, 2005), 179-185.

[6] E. D. Webb, HMS Vernon, 1930-1955. (HMS Vernon: The Wardroom Mess Committee, 1956), 20-25.

[7] Peter Elliot, Allied Minesweeping in World War 2. (Patrick Stephens: Cambridge, 1979), 30-34. For more information specifically on motor minesweepers see: Michael J. Melvin, Minesweeper: The Role of the Motor Minesweeper in World War II (Worcester: Square One Publications, 1992).

[8] An influence mine is a device triggered using sensors to detect the presence of a vessel when it comes into range of the mine’s blast.

[9] Alfred Thayer Mahan. Influence of Sea Power upon History, 1660-1783 (Scotts Valley: Createspace Independent Publishing Platform, 2016), 7-15.

Excellent article Jack. You might want to check out my Twitter account @Sweepers3945 ; we appear to be sweeping the same channel (albeit employing different techniques!)