Cresmina Dune in Cascais, Portugal, 2019. Duna da Cresmina, Cascais, Portugal, 2019. Photographs by the author unless otherwise indicated.

Sand has been a recurring theme here at the Coastal History Blog, from some of my earliest posts, “What are Beaches for?”, “The Political Economy of Sand,” and a bit more indirectly, “Coasts of the Anthropocene,” followed by a post inspired by my nearest coast, the Indiana Dunes State Park facing Lake Michigan. More recently, there was Elsa Devienne’s guest post from 2016 about the Urban Beaches Workshop at the University of London, and of course in 2020, my post on Devienne’s brand-new book about the beaches of Los Angeles, California, which includes some discussion of the emergence of a modern science of sand, erosion, and beach conservation. Joana Gaspar de Freitas’ guest post today is a fine continuation of that tradition. She is the Principal Investigator at the ERC-funded “Sea, Sand and People. An Environmental History of Coastal Dunes” project hosted by the Center for History at the University of Lisbon, Portugal. We are also happy to present for the first time, courtesy of Dr. Gaspar de Freitas, the simultaneous publication of a Coastal History Blog post in English and in Portuguese. – I. L.

Sea, Sand and People: field work. Abu Dhabi, UAE, 2020. O Mar, a Areias e as Gentes: trabalho de campo. Abu Dhabi, EAU, 2020.

As an historian I am often asked why do I study dunes. It seems an odd issue for most people, especially to my own colleagues. Curiously, when I participate in coastal management congresses no one questions my interest about the dunes, the surprise comes when I explain my professional background. We are so used to use labels to define our work and to keep within the limits of our base disciplines that the ones that cross the lines are left in-between, like the dunes, amidst the sea and the land.

Como sou historiadora perguntam-me muitas vezes porque estudo dunas. Parece um tema estranho, sobretudo para os meus colegas. Curiosamente, quando participo em congressos sobre gestão costeira ninguém questiona o meu interesse por elas, a surpresa surge quando descobrem a minha profissão. Estamos tão habitados a usar etiquetas e a trabalhar dentro dos limites das nossas disciplinas que quando alguém cruza estas linhas fica em território de ninguém, como as dunas, entre a terra e o mar.

In one of my favourite books about coastal issues – The beaches are moving – Orrin Pilkey and Wallace Kaufman explain that a beach is a dynamic system always in motion, changing to adapt to new forcing mechanisms.[1] Dunes are part of this dynamic system, so they move too. The sand grains carried by wind can travel inland for miles. This is where my history of dunes begins…

Num dos meus livros favoritos sobre questões costeiras – The Beaches are moving – Orrin Pilkey e Wallace Kaufman explicam que as praias são sistemas dinâmicos sempre em movimento, em constante adaptação a mecanismos de forçamento.[1] As dunas fazem parte deste sistema e também se movem. Os grãos de areia transportados pelo vento podem penetrar quilómetros para o interior. É aqui que a minha história das dunas começa…

Walking in the moving dunes. S. Martinho do Porto, Portugal, 2019. Passeando nas dunas em movimento. S. Martinho do Porto, Portugal, 2019.

Perceptions about specific landscapes are strongly determined by their natural resources and their practical utility for populations.[2] In the 18th and 19th centuries, the dunes were generally described as a monotone vision, a naked territory, a scary desert. Sandy coasts were considered unattractive because of their arid nature, they were not appealing for human beings, especially when compared with a countryside of meadows, streams and agricultural fields.[3] Dunes were then regarded as huge masses of sterile worthless sand. In several regions of Europe and the USA, these big sand-hills, bare of vegetation, blown by the winds, were rolling inwards and burying the soil beneath it, causing the loss of houses, villages and productive fields. They were also considered responsible for silting natural harbours in the mouth of rivers, bringing increasing difficulties to navigation; and for forming lakes and pestilential marshes that flooded the lands and caused diseases.[4] Dunes were referred to as “evils,” “threats,” “enemies,” and compared to “dangerous armies,” a battle was being fought against them.[5]

A ideia que temos sobre determinadas paisagens é determinada pelos seus recursos naturais e utilidade prática.[2] Nos séculos XVIII e XIX, as dunas eram geralmente descritas como visões monótonas, territórios despidos, desertos assustadores. As costas arenosas não eram atractivas porque áridas, sem interesse, especialmente quando comparadas com prados verdes, riachos e campos agrícolas.[3] As dunas eram então grandes montes de areia estéril e inútil. Em várias regiões da Europa e Estados Unidos da América, estas areias, sem vegetação, sopradas pelo vento e levadas para o interior, cobriam tudo à sua passagem, aldeias, casas e terrenos produtivos. Eram também responsáveis por assorear rios e estuários, dificultando a navegação, e formar lagos e pântanos pestilentos onde se geravam doenças.[4] Na literatura é frequente encontrar as dunas referidas como “males”, “ameaças”, “inimigas”, comparadas a “perigosos exércitos”, sendo que, por todo o lado, se travava uma batalha contra elas.[5]

To solve the problem of the “pernicious movement of the sands,” it was considered that the best solution was trapping them with vegetation and trees, with the double purpose of preventing the destruction of arable land and of increasing their economic value by converting them into forest areas.[6] The new forests would improve climate and seasons, protect streams and harbours from silting and provide timber, firewood, planks, resins and tar, resources that nations needed for their development. The task of converting the sterile white sands into green forests was regarded as an urgent need because of the benefits that it could bring to local and national economies. More fundamentally, it was seen as a method of ordering a chaotic nature, creating civilization, using hard human work and technology to build a landscape for the future.[7]

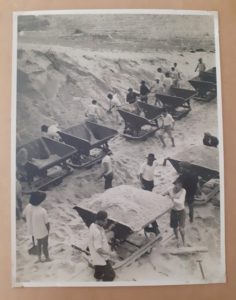

Building a road in the dunes, Portugal. Beginning of the 20th century, José Neiva Archive. Construção de uma Estrada nas dunas, Portugal. Início do século XX, Arquivo de José Neiva.

Para resolver o problema do “pernicioso movimento das areias,”[6] considerou-se que a melhor solução era fixá-las com vegetação e árvores. Isto tinha o duplo propósito de evitar a destruição de terra agrícola e de aumentar o valor económico das dunas transformando-as em florestas. Estas serviriam para melhorar o clima e as estações, protegeriam os rios e portos do assoreamento, e providenciariam madeiras e resinas, recursos de que as nações precisavam para o seu desenvolvimento. A tarefa de converter as areias em verdes florestas foi considerada uma urgência por causa dos benefícios que traria para as economias locais e nacionais.[7]

The dune afforestation solution came from the work of a French engineer, called Brémontier, who in the 18th century had developed a method for dune fixing, based on fencing and planting vegetation and trees. The strategy was used to cover a vast area of Gascony with pines, proving that this could be done successfully on a large-scale. The method spread across Europe and was carried to other parts of the world. Scholarly networks, scientific academies and other formal and specialized institutions seem to have played a role in this knowledge transfer. In Portugal, for instance, Andrade e Silva (1815) was the first to talk about the need of fixing coastal dunes and to put it into practice based on what he had learned while travelling in Germany and France.[8]

Esta solução teve origem o trabalho desenvolvido por um engenheiro francês, chamado Brémontier que, no século XVIII, desenvolveu um método para a fixação das areias, utilizando vedações e plantando vegetação e árvores. A sua estratégia foi posta em prática na vasta área da Gasconha, que ficou coberta por pinheiros, mostrando que era possível aplicá-la com sucesso a larga escala. O método espalhou-se pela Europa e daqui a outras partes do mundo. As redes pessoais de académicos e naturalistas, as sociedades científicas e outras instituições especializadas parecem ter tido um papel fundamental na difusão deste conhecimento. Em Portugal, por exemplo, Andrada e Silva (1815) foi o primeiro a defender a necessidade do plantio das dunas da costa e a desenvolver em Lavos o que aprendera durante as suas viagens pela Alemanha e França.[8]

In the second half of the 19th century, the transformation of dunes into forests was systematically applied: “the maritime pine became a key technology of land reclamation and territorial modernization, as important as drainage ditches, irrigation canals, dikes, roads, railways and bridges.”[9] Portuguese engineers were sent to France to learn dune fixing techniques. This knowledge, first developed in the metropolis, was later taken to Angola and Mozambique.[10] Through the British Empire network dune afforestation also reached Australia and New Zealand.[11] The U.S. Department of Agriculture sent a technician to Europe to learn the methods for reclaiming sand dunes and apply them back home.[12] These works continued through the 20th century, deeply changing coastal landscapes. Many of the reclaimed sands are now public forests or natural parks, like the National Littoral Forest (Portugal), the Culbin Forest (Scotland) and the Oregon Dunes National Recreation Area (USA).

Na segunda metade do século XIX, a transformação das dunas em florestas foi feita de forma sistemática: “o pinheiro marítimo tornou-se uma tecnologia-chave na reclamação de terras e modernização territorial, tão importante como as valas de drenagem, canais de irrigação, diques, estradas, caminhos-de-ferro e pontes.”[9] Nesta época, alguns engenheiros portugueses foram enviados a França para aprender as técnicas de imobilização das dunas. Este conhecimento, primeiro aplicado na metrópole, foi depois levado para Angola e Moçambique.[10] Através das redes do império britânico, chegou também à Austrália e Nova Zelândia.[11] O Departamento de Agricultura dos Estados Unidos enviou um dos seus técnicos à Europa para aprender os métodos de reclamação das dunas para serem depois aplicados em casa.[12] Estes trabalhos continuaram no século XX alterando profundamente as paisagens costeiras. Muitas das zonas reclamadas são hoje florestas públicas ou parques naturais, como as Matas Litorais (Portugal), a Floresta de Culbin (Escócia) e a Área Recreativa Nacional das Dunas do Oregon (EUA).

Perception about dunes changed in the last decades of the 20th century. This is probably connected to the appearance of the ecological movements in some countries and the development of scientific knowledge on natural coastal systems. For centuries, the drifting sands were a major problem for population living near the ocean. But now, sand has become a much-sought commodity, as human activities are reducing the amount of sediments arriving to the seashore by diverting it for land filling, construction and industries.[13] Also dunes are being destroyed by urbanization, sand mining, people and vehicles passing by. At the same time, coastal protection has become a top priority because of climate change and the expected mean sea level rise and dunes were discovered to be the best natural defence against storm flooding, as they work as buffer areas protecting human infrastructures placed on the shore.[14] So, all around the world, coastal managers and scientists are working in dune systems rehabilitation, but with little awareness of the lessons from past attempts and failures.

Leisure buildings in the dunes. Florianópolis, Brazil, 2019. Estruturas de lazer nas dunas. Florianópolis, Brasil, 2019.

Nas últimas décadas do século XX, a percepção sobre as dunas mudou. Isto está provavelmente relacionado com o aparecimento dos movimentos ecologistas em alguns países e o desenvolvimento do conhecimento científico sobre os sistemas naturais costeiros. Durante séculos, as areias foram um problema para as populações que viviam perto do mar. Mas, hoje tornaram-se um recurso muito procurado, à medida que as actividades humanas foram reduzindo a quantidade que chega ao litoral, desviando-as para a construção e indústria.[13] As dunas estão ainda ameaçadas pela extracção de areia, urbanização e pisoteio de pessoas e veículos. Ao mesmo tempo, a protecção costeira tornou-se uma prioridade, por causa das alterações climática e da subida do nível do mar, e as dunas são consideradas a melhor defesa natural contra as inundações marítimas, já que funcionam como áreas-tampão protegendo as construções erguidas na praia.[14] Assim, um pouco por todo o mundo, cientistas e gestores costeiros procuram reabilitar os sistemas dunares, experimentando novas técnicas, mas pouco sabem sobre as experiências, tentativas e erros, das intervenções anteriores.

Most studies on dunes are about sand and natural processes; however, thinking about them as historical subjects means looking from a different angle, focusing on their relation with humans, by analysing fears, local economies, traditional and technical knowledge, land reclamation, forest exploitation, state power, risks and vulnerabilities, coastal management policies and nature restoration. This offers the opportunity to cross time (past, present and future), space (local and global), actors (human and non-human) and disciplines (natural and social sciences) to do an entangled history of coastal environments.

One of the things I love most about my job: Friends send me pictures of dunes from all over the world! Like this one from The Hamptons by Sophia Kalantzakos. Uma das coisas de que mais gosto no meu trabalho: os amigos enviam-me fotografias de dunas do mundo inteiro! Como esta tirada nos Hamptons (EUA) pela Sophia Kalantzakos.

A maioria dos estudos sobre as dunas debruçam-se sobre a areia e os processos naturais, pensar nelas como objectos históricos oferece um novo ângulo de análise, com foco na sua relação com os seres humanos, observando outros elementos, como os medos ancestrais, as economias locais, o conhecimento tradicional e técnico, a reclamação de terras, a exploração florestal, o poder estatal, os riscos e vulnerabilidades, as políticas de gestão costeira e a restauração da natureza. Isto permite cruzar diferentes componentes, tempo (passado, presente e futuro), espaço (local e global), actores (humanos e não-humanos) e disciplinas (ciências naturais e sociais, humanidades), para construir uma história interligada das zonas costeiras.

Notes

[1] Wallace Kaufman and Orrin Pilkey, The Beaches Are Moving. The Drowning of America’s Shoreline (Garden City, New York: Anchor Press / Doubleday, 1979).

[2] Verena Winiwarter, Martin Schmid, and Gert Dressel, “Looking at Half a Millennium of Co-Existence: The Danube in Vienna as a Socio-Natural Site,” Water History, vol. 5, no. 2, (2013), 101–19.

[3] Nicolas-Théodore Brémontier, “Mémoire Sur Les Dunes, et Particulièrement Sur Celles Qui Se Trouvent Entre Bayonne et La Pointe de Grave, à l’embouchure de La Gironde,” Annales des Ponts et Chaussées, 1.ª serie, tome V, (Paris: Chez Carrillian-Goeury, Libraire-Editeur, 1833 [1796]); Carlos de Sousa Pimentel, Arborização dos Areaes do Littoral (Manuscript, 1873); George Bain, The Culbin Sands or The Story of a Buried Estate (Nairn: Nairshire Telegraph Office, 1900).

[4] Brémontier, “Mémoire sur les Dunes”; “Culture Forestière. Extraits des Ouvrages Forestiers de M.M. Hartig et de Burgsdorff, sur les moyens de fixer les sables et de les planter en bois,” traduits de l´allemand et communiqués par M. Baudrillart. Annales de L´Agriculture Françoise, tome XXVI, (Paris: Librairie de Madame Huzard, 1806); George Perkins Marsh, The Earth as modified by Human Action. A last Revision of “Man and Nature”, (New York: Charles Scribners´s Sons, 1907); “Damage done by sand drifting on Oregon coast may be prevented by planting trees,” The Sunday Oregonian (May 8, 1910).

[5] M.M. Gillet-Laumont, Tessier and Chassiron (1833), “Rapport sur les différens memóires de M. Brémontier,” Annales des Ponts et Chaussées, 1.ª serie, tome V, (Paris: Carilian-Goeury, Libraire-Editeur, 1833); José Bonifácio de Andrade e Silva, Memória sobre a Necessidade e Utilidades do Plantio de Novos Bosques em Portugal, (Lisboa: Typographia da Academia Real das Sciencias, 1815); “Efforts to stay shifting sand of the Columbia presents hard problem,” The Sunday Oregonian, (March 7, 1904).

[6] Carlos Ribeiro and Nery Delgado, Relatório acerca da arborização geral do país apresentado a sua Ex.ª o Ministro das Obras Públicas, Comércio e Indústria em resposta aos quesitos do artigo 1.º do decreto de 21 de Setembro de 1867, (Lisboa; Tipografia da Academia das Ciências, 1869), 69.

[7] Samuel Temple, “Forestation and its Discontents: The Invention of an Uncertain Landscape in Southwestern France, 1850 – Present,” Environment and History, vol. 17, (2011), 13-34; Thomas Hughes, Human-built world. How to think about Technology and Culture, (Chicago and London: University of Chicago Press, 2005), 29-30; Manuel Alberto Rei, Arborização. Alguns artigos de propaganda regionalista, (Figueira da Foz: Tipografia e Papelaria Costa, 1940); Willard McLaughlin and Robert Brown, Controlling Coastal Sand Dunes in the Pacific Northwest, (Washington, D.C.: United States Department of Agriculture, 1942).

[8] Silva, Memória.

[9] Temple, “Forestation”, 18.

[10] Júlio Alfaro Cardoso, “Fixação das Dunas em Moçambique,” Boletim da Sociedade de Estudos da Colónia de Moçambique, vol. 57-58, (1948), 1-17; Pompeu Ferreira Almeida, “Fixação de dunas na Baía dos Tigres,” Agronomia Angolana, vol. 13, (1961), 79-89.

[11] James Beattie, Empire and Environmental Anxiety: Health, Science, Art and Conservation in South Asia and Australasia, 1800–1920, (Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2011).

[12] A.S. Hitchcock, “Methods used for controlling and reclaiming sand dunes,” Bureau of Plant Industry – Bulletin, n.º 57, (Washington: Government Printing Office, 1904).

[13] John Gillis, The Human Shore. Seacoasts in History, (Chicago and London: The University of Chicago Press, 2012).

[14] Nicole Elko et al., “Dune Management Challenges on Developed Coasts,” Shore & Beach, vol. 84, no. 1 (2016), 1–14.

Thank you, Joana, for this very interesting piece about dunes. I thought you might also enjoy browsing the wonderful blog by my dear friend, the late Dr Michael Welland, who died in 2017 – in Through The Sandglass there is everything about sand and deserts, the science, art, engineering, landscaping, Mars … https://throughthesandglass.typepad.com/through_the_sandglass/

(I did also write a short piece about sand-ripples and sand-waves myself, some years ago – having realised I knew so little about their formation https://solwayshorewalker.wordpress.com/2016/02/08/some-things-i-didnt-know-about-sand-ripples-and-the-sea/. Some attempts were made to stabilise some of the dunes along the Solway Firth with willow hurdles, but the hurdles were washed away!)