Historic wooden barge at Red Hook with the Statue of Liberty in the distance. All photos by Isaac Land, unless otherwise noted.

It’s easy to bury New York City underneath a list of superlatives. On this visit, my Airbnb was in Astoria, offering me the refreshing, if fleeting, experience of living in Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez’s Congressional district. On a Saturday night, I took the 7 train out to Queens Night Market. The Night Market is something like a cross between a really good county fair and a tour of the whole world. Even people who live along the 7 line speak of it in some awe; the subway runs through the most diverse string of neighborhoods in the United States, with 160 languages spoken.

My focus here, though, is on a different aspect of the city, and a different list of superlatives. I’ve blogged before about South Street Seaport, but that represents only a small fraction of the picture. Spanning seven bays and multiple islands, New York City has at least 520 miles of shoreline (some other estimates are higher).[1] It has one of the world’s largest natural harbors. In the mid-twentieth century, it became for a time the world’s busiest port, serviced by 13 railroads, lined by “1,822 docks, wharves, and piers” and more than a thousand warehouses.[2]

The Hudson River, facing the Goldman Sachs building in Jersey City. This elegant vista is in a long tradition of using the waterfront for display and opulence. For a different, more environmentally-conscious perspective on the Hudson River estuary, see The River Project (Twitter: @riverprojectnyc).

Despite this, with the advent of bridges and tunnels, in recent times many people haven’t necessarily experienced the view from the water. The Circle Line is an eye-opener, but it is just a sightseeing cruise; the Staten Island ferry is more utilitarian, but it runs only one route. On this visit, I was very impressed with NYC Ferry (Twitter: @NYCFerry), a new service which is affordable and offers a variety of routes. It has the potential to make overlooked segments of New York’s watery world accessible to visitors and residents alike. The view from the water also makes some of the city’s infrastructure and planning choices much more visible. (It’s also a slow, embodied experience; I arrived at Wall Street from Astoria with unsteady feet from bobbing about on the East River for so long!)

The East River, on a misty day viewed from underneath Manhattan Bridge on the Brooklyn side. Kara Schlichting notes that the East River is not a river, but “an eighteen-mile tidal strait of [Long Island] Sound.”

When I was packing my bag for this trip, I saw that Kara Schlichting was giving a talk about her new book New York Recentered: Building the Metropolis from the Shore at the Skyscraper Museum. I’d already been hearing some buzz about this book, so I took it as an amazing fortunate coincidence that I could go and hear her talk about her work, even on this short trip. New York Recentered develops a number of themes that will be close to the heart of regular readers of this blog. “The coast is a particularly useful frame with which to study environmental change in a city of islands,” she writes, “because the city’s real estate market, recreational networks, shipping and manufacturing interests, and public works authorities all had vested interests in coastal access… Competition between different users over the shore reveals the complexity of coastal urbanization and its environmental transformations.”[3]

One of the few remnants of the 1939 World’s Fair on site. Chapter Six of New York Recentered is all about how Flushing Meadows was transformed from a vast wetland into a despised ash heap and dumping ground, but then ostentatiously “reclaimed” for the Fair.

There’s a lot in Schlichting’s book about drainage, sewers, refuse, and odors. She also offers vivid descriptions of the texture of waterscapes and wetlands in all their muddy glory, from “salt hay fields” to a “fibrous crust, known as meadow mat… [underlain with] gummy sediment.”[4] In a way, it was ironic that the Skyscraper Museum, with its self-proclaimed mission to foster an understanding of the skylines of “the world’s first and foremost vertical metropolis,” gave a podium to a historian who is so exuberantly concerned with the submerged, the squishy, and the terrain most resistant to building. However, they also host a wide-ranging speaker series related to urban history and urban planning issues, and this aligns perfectly with another running motif in New York Recentered, the battles of developers, property owners, and regulators with the unruly pressures of a metropolis with a growing population.

Schlichting notes the aspiration to fashion Flushing Meadows Corona Park into the twentieth-century version of Central Park. Even today, it offers much-appreciated green space that’s convenient to some of the city’s most diverse neighborhoods.

While Schlichting’s talk at the Skyscraper Museum concerned only the machinations of Robert Moses and his transformation of Flushing Meadows by administrative fiat, I learned a lot from her other chapters about what might be called the popular democracy of leisure. While access to water and the pleasant sea breezes appealed to absolutely everyone, coastal recreation for the masses—paralleling developments in amusement parks—was increasingly color-coded.[5] Further, when African-American entrepreneur Solomon Riley undertook to build a beach resort in the Bronx, he was blocked by licensing commissions for much of the 1920s, first in his effort on Hart Island, and later at a different location at Throg’s Neck. A black resort was “an unthinkable neighbor for the white enclaves of the North Shore.”[6] Meanwhile, on Long Island’s Gold Coast, some of America’s richest families sought to incorporate a series of “estate villages” with ordinances uniformly banning parked cars or even “meeting on sidewalks.”[7] The impetus in these examples is more often patchy and bottom-up than decreed from City Hall or the Statehouse, even if the “bottom-up” sometimes involved a clique of millionaire’s lawyers appointing themselves as a village council and blocking day-tripping beachgoers with a stroke of a pen.

Of course, the tension between access and exclusiveness, imperious planners and maverick improvisers on the shoreline is an ongoing conflict, even where no recreational beaches are involved. The next day I was in Brooklyn’s Dumbo neighborhood (short for Down Under Manhattan Bridge Overpass), a derelict postindustrial warehouse district on the East River which has become extensively gentrified just within the last twenty years. A New York Times profile from 2007 relates how residents invented the name Dumbo “in the hope that a silly, ugly name would keep developers away.” It was not to be; Dumbo was too centrally located, and too convenient to Manhattan. While one resident recalled how “a pack of feral dogs used to hunt rats in the street” when she first moved to the area in 1992, by the mid-2000s Dumbo was already adjusting to its first luxury apartments.[8]

A street in Dumbo. Some developers strike a self-conscious balance, carefully preserving the rough waterfront or warehouse look, as if they’d just moved in yesterday and were still renovating.

By 2019, so much effort has gone into developing attractive parks along the East River, and there are so many pastry shops and yoga studios, that it can be a little hard for a first-time Dumbo visitor to visualize the time when this was a working waterfront (or even an abandoned and decaying waterfront). Above Time Out Market, which just opened in March of this year (21,000 square feet of lunch options from avocado toast to “a kosher steakhouse with a French- and Asian-influenced menu”), you can find the Brooklyn Historical Society’s Waterfront exhibit at DUMBO (Twitter: @brooklynhistory), which makes a valiant attempt to remind visitors that they are actually inside the former Empire Stores warehouse.

It was just one of many; according to the exhibit, on the waterfront just between Dumbo and Red Hook alone, there were 70 warehouses, and Brooklyn was dubbed “The Walled City” after this rampart of imposing buildings.

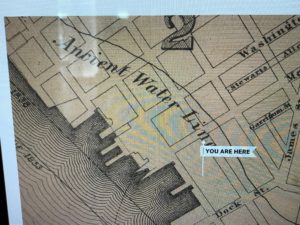

It can be hard to stay aware of when you have crossed over to land that used to be below the waterline. A video featurette elsewhere in the BHS’ Waterfront exhibit offers reflections on how Brooklyn is planning to adjust to rising sea levels, since water will tend to reclaim these low-lying areas first.

I was struck by the prominent place of Linebaugh and Rediker’s Many-Headed Hydra in the tiny museum gift shop. This wasn’t a haphazard choice; BHS’ Waterfront exhibit is very much in that tradition of oceanic history. It uses the circulations of coffee, spices, grain, sugar, and jute to place one Brooklyn warehouse in the context of many continents, many oceans, and of course the larger structures of nineteenth-century globalization and imperialism. It considers who worked in the warehouses, what their work was like, and safety conditions (or lack thereof). There is also an arresting portrayal of slavery in Brooklyn, which persisted later than you might think.

I was meeting Sean Fraga at Brooklyn Roasting Company, but I took a detour up the hill to check out the building site at 85 Jay Street, a billion-dollar project involving a whole city block which has drawn involvement from Jared Kushner and (it’s rumored) some Saudi investors. (Apartments already for sale! The developers’ website is here.) When I stopped by, there were at least 100 workers on the site, and a whole convoy of cement mixer trucks on a nearby street. The trucks lined up as if for a parade, and a worker had to direct traffic at a nearby street corner, waving them through at an excruciatingly slow pace. It was only possible to get one cement mixer through the intersection before the light would turn red again.

Red Hook, Brooklyn. I took this picture because this tidy, self-consciously “cute” marketing was such a contrast to other aspects of the area.

The next day I was in Red Hook, a different Brooklyn neighborhood, with elements of a working waterfront still in use. Despite the tone of some recent press coverage, my sense was that Red Hook retains something of a split personality between tiny gentrified enclaves, and a patchwork of quirky, gritty, unexpected survivals from earlier incarnations of the neighborhood. Although the Manhattan skyline is plainly visible (from some spots, all the way up to Midtown) and the views of the Statue of Liberty are particularly good, Red Hook is also notoriously hard to access via public transit. The advent of the NYC Ferry stop is a significant development, connecting Red Hook to Dumbo and Wall Street, although it is new enough that it doesn’t seem to be attracting lots of passengers yet.

Gina Pollara has written: “The engineering feats accomplished in the waters around Manhattan Island were dwarfed by those achieved in the waters off Brooklyn.” She is referring to the construction of the Atlantic Basin (from the 1840s) and the still larger Erie Basin (opened in 1864) which “encompassed 135 acres,” themselves just pieces of “one vast configuration of huge shipbuilding and repair facilities, sugar refineries, and enormous storehouses for bulk items such as coffee and grain” that would emerge by the early twentieth century.[9] It is another reminder of the contrast between New York’s vertical achievements (the instantly recognizable skyscrapers) and the less visible, yet no less important, horizontal expanse of New York’s watery world.

The NYC Ferry disembarks its passengers inside the Atlantic Basin, so I got a good look at that. I regret that I did not make it over to the Erie Basin on this trip. It contains remnants (the caisson, the outline of the graving dock in cobblestones) of what was once an iconic feature of the Red Hook waterfront—the gigantic graving dock—site of a major controversy in the mid-2000s when IKEA proposed to fill it in to create a parking lot for their new store—and did.” [10] Although IKEA ultimately prevailed, the graving dock debate prompted some interesting counter-proposals, and some soul-searching. I know many readers of this blog have considered (or participated in) similar debates about how to balance development and investment with the need to preserve the distinctive maritime character and heritage of an area, and in Red Hook, the community was trying to keep the graving dock working.

This sign at PortSide NewYork requesting volunteers also speaks to the complexity of its mission and outreach activities.

Johnathan Thayer had arranged for me to meet some of the luminaries of public history and community outreach in Red Hook, starting with Carolina Salguero at PortSide NewYork (Twitter: @PortSideNewYork). PortSide’s mission is to “bring the community ashore and the community afloat together, for the benefit of all.” This takes many forms, including tours of the historic oil tanker Mary A. Whalen for local schoolchildren, many of whom have never been aboard a vessel or really explored a waterfront of any sort, and hosting an eclectic collection of oral history #waterstories on their website, which I’m hoping to explore in more depth (there is a lot there).

PortSide has also been honored at the White House and by the Governor of New York for their work during and after Hurricane Sandy in 2012. After weathering the storm themselves, PortSide set out to help their neighbors at a time when Red Hook had lost electricity, phone, and internet connections:

“The result was an only-in-Red-Hook blend: an aid station run by a maritime organization in a real estate office that was also an art gallery. PortSide gathered volunteers off the street to get six computer workstations, office furniture and equipment from PortSide’s offices on the tanker to set up at ‘351’… ‘351’ became a haven for people — to escape the cold, to charge cell phones, iPads, and power tools, to check e-mail[,] to blow up a new air bed, to start the FEMA application or an insurance claim, or to wait for an escort to enter an apartment building whose electronic doors didn’t lock without power.”[11]

Aboard PortSide NewYork’s Mary A. Whelan. L to R: Isaac Land, Carolina Salguero, Johnathan Thayer. Photo credit: Carolina Salguero

Maritime histories and historic ship restoration efforts can have somewhat narrow associations. PortSide NewYork has from the start decided to have future-focused advocacy and have program content be more inclusive. For example, their website offers an African-American maritime heritage program, addressing the topic nationally, not just locally. Carolina Salguero shared with me a number of interesting examples of how PortSide’s Facebook comments section has elicited a lot of sharing and engagement when this subject matter came up. It’s nice to hear about an example where interaction on social media produces a collaborative and constructive response.

Chiclet made an appearance right after I left, so I was unable to present my blogger credentials and ask her questions. The Mary A. Whalen’s ship’s cat has her own web page and is writing a memoir. Photo credit: Carolina Salguero.

My next stop with Johnathan was the Waterfront Museum, where David Sharps holds three titles: “President, Entertainer, Captain.” A former professional circus clown and juggler, Sharps first encountered people living on barges during his apprenticeship working in European circuses. Returning to the US, Sharps came across one of the many abandoned wooden barges in New Jersey that had been rendered obsolete by the development of container shipping. He bought the Lehigh Valley No. 79 for a dollar in 1985, pumped out the water and harbor mud, and ultimately came to live on the renovated barge with his family. As with the Mary A. Whalen, offering a complete accounting of all the roles that the barge performs is probably beyond my abilities here. It serves as a museum and historical landmark, standing in for the thousands of similar craft that were once pushed around New York Harbor by tugboats, but it also doubles as a performance space (in keeping with Sharps’ circus/theatrical background). In addition, it is sometimes the venue for exhibits that reach well beyond the Lehigh Valley No. 79’s particular backstory, such as the wide-ranging Waterfront Heroes display.

I have sometimes blogged about the potential for coastal history to break down some of our assumptions about where the maritime begins or ends (or indeed where maritime heritage or public history begins or ends), so it was good for me to get a taste of how nonprofits like PortSide NewYork and the Waterfront Museum navigate those particular waters, and manage their outreach and community partnerships.

Aboard the Waterfront Museum’s Lehigh Valley No. 79. L to R: Stefan D-W (Dreisbach-Williams), Johnathan Thayer, Isaac Land, David Sharps. Image credit: Muriel Abeledo.

My starting point, years ago, for thinking about coastal history was considering the large numbers of people who lived on waterfronts but didn’t go out to sea, and also those who undertook voyages on the water but rarely (or never) got out of sight of land. River, canal, and harbor barges weren’t especially on my radar back then, but aboard the Lehigh Valley No. 79 I got a quick tutorial on how barge operators would live, with their families, in a little cabin mounted on top of the barge. A picture-book brochure aimed at visiting kids explains how, in the heyday of the barge era, schoolchildren managed the problem of getting home to their barge cabin, when the barge would have moved during the day and wasn’t docked where it had been that morning.

From the Red Hook waterfront, New York harbor extends seemingly to the horizon in almost every direction. Here, the view is toward the docks at Bayonne, New Jersey. For a startling new initiative to transform these waters, see the Billion Oyster Project (Twitter: @BillionOyster).

Another abiding interest of mine, of course, has been how waterfronts related to the larger urban environment, especially in ways that don’t align neatly with the preoccupations of economic history or naval history. I mentioned to Carolina Salguero the Brooklyn Historical Society’s fondness for the image of warehouse ramparts and the Walled City nickname, but she quickly poked holes in that thesis, directing me to her oral history interview with Sunny Balzano, who grew up near the harbor during World War Two. In track two of the interview, Balzano relates how the Red Hook boys, “small and devious,” found ways to climb over rooftops to bypass the walls and gates that kept them away from the docks, and reach the water, jumping in “bare ass” on a dare. The harbor was polluted in every sense of the term; in track three, Balzano describes how the boys would draw straws to determine which of them would go first and clear a path with a breaststroke, brushing the turds and fish heads out of the way for the queue of swimmers behind. He repeatedly likens the harbor water to swimming in a “toilet bowl,” and also recalls encounters with dead pigs and floating, mostly decomposed, human corpses. The boys nevertheless relished the challenge, despite the filth and treacherous currents, and returned to swim long distances again and again.

I didn’t spot any naked daredevil children in New York Recentered, but readers can pick out some renegades here and there, reading against the grain of council meeting minutes that despaired over trespassers who cut across yards, interlopers who pitched tents on the shore during a heat wave, not to mention the eager swimmers who used their cars as changing rooms, in full view of anyone who might happen by.[12] These kinds of stolen moments and seized opportunities, by their nature, leave a trace for us mostly if someone was particularly unsubtle, or had the bad luck to get caught.

Where I stood to take this picture is too far back to be the vantage point for the Edward Casey “Stevedores Bathing” painting, but I think he was standing roughly where Jane’s Carousel is today (in my photo, visible in its glass box enclosure).

The Brooklyn Historical Society’s online exhibit On the Queer Waterfront showcases one example where informal sea bathing found a thoughtful eyewitness. Edward Casey’s painting “Stevedores Bathing Under Brooklyn Bridge” (1939) juxtaposes the bodies of perhaps twenty naked young men against the backdrop of the iconic urban landmarks of the Bridge and Wall Street’s skyline. It is a painting that is susceptible to many different interpretations, of course, but one interesting point of tension is between visbility and invisibility. This group of men is naked together in a completely public and exposed way, and yet the exact location means that virtually no one in the skyscrapers or on the bridge is going to notice at all. I’m probably overfond of the expression “hidden in plain sight,” but this is a great example.

It’s fascinating to consider how spontaneous public swimming disrupted boundaries and expectations, not to mention any notions of licensing and zoning. This sort of thing won’t leave a continuous and comprehensive archival record, like the inventory of a warehouse. But for me, this serves as another reminder that there’s nothing small about microhistory. One striking exception dislodges our assumptions; a single naked swimmer in an unexpected place suggests the possibility of a whole unstudied world.

[1] “520 Miles of Waterfront to Get Long-Range Plan,” New York Times, 13 March 2011. Some of the discrepancy in estimates may have to do with whether you are measuring New York Harbor, which conventionally includes areas in New Jersey as well, or measuring waterfront in the five boroughs alone.

[2] Benjamin W. Labaree, et al., America and the Sea: A Maritime History. (Mystic, CT: Mystic Seaport, 1998), 602. See also http://waterfrontmuseum.org/history , accessed 18 June 2019.

[3] Kara Schlichting, New York Recentered: Building the Metropolis from the Shore. (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2019), 13.

[4] Schlichting, New York Recentered, 191, 206. See also the description of the Harlem River on page 72.

[5] Schlichting, New York Recentered, 109.

[6] Schlichting, New York Recentered, 111.

[7] Schlichting, New York Recentered, 166-167.

[8] “Dumbo Journal: District Trying to Forge a New Identity,” New York Times, 25 December 2007.

[9] Gina Pollara, “Transforming the Edge,” in ed. Kevin Bone, ed. The New York Waterfront: Evolution and Building Culture of the Port and Harbor, revised and updated edition (New York: Monacelli Press, 2004), quoted pages 167, 176.

[10] For a taste of the debate and reaction to IKEA’s plans for the site, see “Sailing into History,” New York Times 3 July 2005; “Awaiting a Big Blue Box and an Altered World,” New York Times 16 June 2008; “Brooklyn Neighbors Admit a Big Box Isn’t All Bad,” New York Times 10 August 2008.

[11] “PortSide NewYork wins White House ‘Champions of Change’ Sandy Recovery Award,” portsidenewyork.org, accessed 18 June 2019.

[12] Schlichting, New York Recentered, 169.

Comments are closed.