Today’s guest post is from Sean Fraga, who recently received his Ph.D. in History from Princeton University, where he is currently a postgraduate research associate with the Center for Digital Humanities and the Department of History.

Here, he discusses the genre (and rhetoric) of bird’s-eye view maps. Reconstructing how the different pieces of an urban area fit together is challenging; these maps, at least, offer us an integrative glimpse as a contemporary wished us to see it. As he notes, they are especially good at suggesting the imbrications of the terrestrial and maritime realms. Readers may want to click on the links to the Library of Congress; the experience of zooming into the detail in these maps is a delight. While some of the port towns mentioned here will be familiar, international readers may not have thought much about Duluth, Minnesota, which is on Lake Superior. One of my favorite things about how coastal history has worked out in practice is to watch how scholars can apply it to settings that were only on the periphery of my attention when I developed the term. The first coastal history conference was called “Firths and Fjords”; Sean’s use of a Great Lakes port is a great reminder of all the various interstitial watery spaces that fit into a coastal paradigm.

— I.L.

Port cities are most themselves when seen from above. This perspective reveals the tight connections between city and harbor: The fingers of wharves reaching seaward and the skein of streets running landward. Maps and charts can provide this perspective on port cities, but one cartographic form, the bird’s-eye view map, captures this viewpoint especially well. Unlike most maps, bird’s-eye view maps, sometimes called panoramic maps or balloon maps, depict their subjects from an oblique perspective. The viewer seems to hover above the horizon while looking forward and down, presenting a view similar to what a bird might see from on high. This was a particularly popular method of representation for American and Canadian cities and towns during the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries.[1] Bird’s-eye view maps are sometimes dismissed as decorative illustrations—the type of thing that might lend atmosphere to a waterfront pub. But these maps offer coastal historians a particularly rich set of potential evidence because of their ability to capture key urban elements, their creators’ goals, and change over time.

Bird’s-eye view maps of coastal cities often depict urban waterfronts in great detail. John Reps argues that these maps are valuable historical sources because they “combine cartographic and pictorial qualities.” By doing so, Reps writes, they “reveal street patterns, relative sizes of lots, relationships between major land uses, the location of public buildings and open spaces, and many other elements of the physical structure of urban communities.”[2] Many maps also include an explanatory key, which offers additional insights.

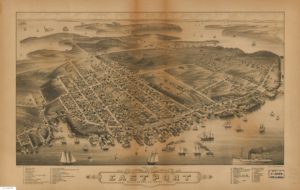

Bird’s eye view of Eastport, Washington Co., Maine, 34 x 59 cm. (Madison, Wisc.: J. J. Stoner, 1879). Library of Congress. https://www.loc.gov/item/76695272/

An 1879 map of Eastport, Maine, identifies the names or owners of nearly all the wharves along the city’s waterfront, along with the city’s Customs House and fish dealers.

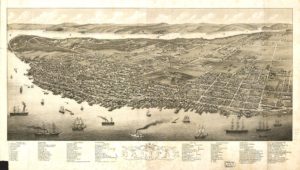

A. Ruger, Panoramic view of the city of Halifax, Nova Scotia, 42 x 91 cm. (Halifax?: s.n., 1879). Library of Congress. https://www.loc.gov/item/73693337/

A map of Halifax, Nova Scotia, from the same year, identifies “government property,” including Admiralty House and Her Majesty’s dockyard, marine hospital, and ordnance yard.

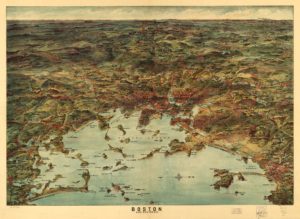

Sometimes, bird’s-eye view maps place their subject in a wider, regional perspective, as with a 1905 map of “Boston and environs.” This map shows the city’s outer and inner harbors, including the lighthouses and navigational aids that guided ships in and out; red and black lines onshore trace rail connections into the city’s hinterland. Bird’s-eye view maps show both specific features and larger context of urban waterfronts.

Boston and environs, 49 x 71 cm. (Boston: Geo. H. Walker & Co., 1905). Library of Congress. https://www.loc.gov/item/75694560/

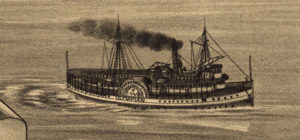

At the same time, though, these maps were frequently used to advertise the cities they depicted. David Hamer cautions that bird’s-eye view maps can “depart from reality so as to emphasize and exaggerate order, progress, prospects for future unlimited growth, and other themes dear to the hearts of urban boosters.”[3] These maps were sometimes funded by local subscription, then distributed widely to showcase urban growth, especially for cities in the North American West. Because of this, many maps show urban harbors as alive with ships—and these ships can act as clues for how a city wanted to portray itself.

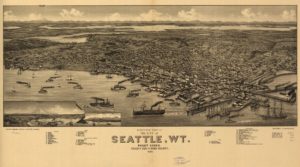

H. Wellge, Bird’s eye view of the city of Seattle, W.T., Puget Sound, county seat of King County, 34 x 83 cm. (Madison, Wisc.: J. J. Stoner, 1884). Library of Congress. https://www.loc.gov/item/75696661/

One such map, of Seattle in 1884, crowded an astonishing thirty-two vessels into the city’s harbor: craft of all sizes and varieties; at dock and at anchor; under sail, steam, and tow—harbor activity as synecdoche for urban potential. Several ships’ names are just visible, picked out in tiny letters on their tiny hulls: the Olympian, the Evangel, the Queen of the Pacific, the McNaught.

These inclusions advertised Seattle’s expansive maritime connections: In 1884, the Olympian ran to Victoria, B.C.; the Queen of the Pacific to San Francisco. They also showed off local industry: Both the Evangel and the McNaught were built at Seattle.[4] The promotional aspects of bird’s-eye view maps offer an additional layer of historical data.

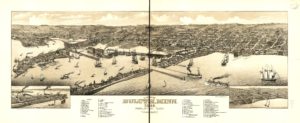

But perhaps the most powerful use of bird’s-eye view maps is to trace change over time. Two maps of Duluth, Minnesota, from 1883 and 1887, illustrate dramatic changes to the city’s harbor in only a few years.

H. Wellge, View of Duluth, Minn., 31 x 101 cm. (Madison, Wisc.: J. J. Stoner, [1883]). Library of Congress. https://www.loc.gov/item/75694637/

H. Wellge, Perspective map of Duluth, Minn., 46 x 104 cm., (Duluth?: Duluth News Co., [1887]). Library of Congress. https://www.loc.gov/item/75694638/

Although the maps use slightly different perspectives, they show how a section of Duluth’s shoreline was transformed from tidelands and mudflats into railroad wharves. The 1887 map, perhaps anticipating future development, also traces the established harbor line. Another map, of Seattle, shows how bird’s-eye view maps reward careful scrutiny: In Native Seattle, Coll Thrush points out a “tiny flotilla of Native canoes” near an on-shore indigenous camp, visible on an 1878 bird’s-eye view map of Seattle. He argues that their “matter-of-fact” inclusion on the map suggests that “real Indian people still had a place in Seattle’s social and economic life in 1878.”[5] The camp and canoes do not appear on later Seattle maps. The illustrative nature of bird’s-eye view maps allows them to dramatically capture urban development and shifting waterfront uses.

Best of all for the interested researcher, bird’s-eye view maps are everywhere. The Library of Congress holds more than fifteen hundred such maps, scanned and accessible online in its Panoramic Maps collection, and these maps are a staple of archival collections at universities, libraries, and historical societies across North America. More than just illustrations, bird’s-eye view maps maps are visual evidence of waterfront infrastructure, maritime connections, and harbor development, offering a unique visual and historical perspective on waterfront cities. Look closely—you might be surprised by what you see.

[1] Eva H. Dodsworth, A Research Guide to Cartographic Resources: Print and Electronic Sources (Lanham, Md.: Rowman & Littlefield, 2018), 223. Dodsworth includes a list of such maps, listed by state or province.

[2] John Reps, Panoramas of Promise: Pacific Northwest Cities and Towns on Nineteenth-Century Lithographs (Pullman, Wash.: Washington State University Press, 1984), 29.

[3] David Hamer New Towns in the New World: Images and Perceptions of the Nineteenth-Century Urban Frontier (New York: Columbia University Press, 1990), 49.

[4] Ship information is from Lewis & Dryden’s Marine History of the Pacific Northwest, ed. E. W. Wright (New York: Antiquarian Press, Ltd., 1961 [Portland, Ore.: The Lewis & Dryden Printing Company, 1895]). Olympian: 77, 316-317, 322-323. Queen of the Pacific: 324. Evangel: 296-297. McNaught: 466.

[5] Coll Thrush, Native Seattle: Histories from the Crossing-Over Place (Seattle: University of Washington Press, 2007), 66-67.

Comments are closed.