There remains a stereotypical image of Jack Tar as a man with loose morals who enjoyed himself ashore whenever he got the opportunity. Yet, how far this stereotype stands up has increasingly been questioned by historians.[1] This article does not intend to join in this debate per se but rather to reflect on the stereotype through the spectrum of the First World War and, more importantly, examine what sailors thought by considering their diaries. It is important to remember that, although sailors are primarily considered as existing solely aboard ship, they also existed upon land and interacted with the ports that they visited.[2] Again, this is not an in-depth analysis of all the factors relating to the Jack Tar stereotype and leave in general, but rather an insight into current research.

There remains a stereotypical image of Jack Tar as a man with loose morals who enjoyed himself ashore whenever he got the opportunity. Yet, how far this stereotype stands up has increasingly been questioned by historians.[1] This article does not intend to join in this debate per se but rather to reflect on the stereotype through the spectrum of the First World War and, more importantly, examine what sailors thought by considering their diaries. It is important to remember that, although sailors are primarily considered as existing solely aboard ship, they also existed upon land and interacted with the ports that they visited.[2] Again, this is not an in-depth analysis of all the factors relating to the Jack Tar stereotype and leave in general, but rather an insight into current research.

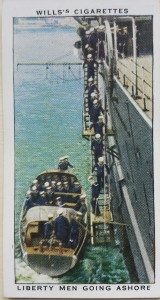

Shore leave represented a welcome break from disciplined life aboard British warships and the amount of leave granted had steadily increased between the last decades of the nineteenth century and the Great War.[3] However, the declaration of war in August 1914 resulted in the cancellation of leave and lengthy periods spent aboard ship. This affected sailors whether stationed in home waters or across the empire and was a cause for much grievance amongst seamen. Sailors were evidently aware of the time between visits ashore and often recorded in their diaries how long it had been since they last had leave.[4] It is therefore understandable that they occasionally let themselves go, sometimes with a bit too much gusto.

This brings us back neatly to the rowdy Jack Tar stereotype. Interestingly sailor diaries record an increase in the number of accidents when sailors who had been ashore returned to the ship.[5] Although not specifically mentioned, it can be inferred that this was often the result of either drunkenness or ‘skylarking’.[6] But what did Jack get up to ashore? Sadly how they spent their leave is not always well recorded.[7] However, sailors did record in their diaries tales of run-ins with the police/authorities. Walter Dennis noted sailors being reprimanded for ‘interference with the Military Guard’, and looking at diaries from before the war it is apparent that this was not uncommon.[8] Henry Baynham, however, has argued that much rested on residents’ attitudes and that they were less tolerant of ‘feeling[s] of high spirits ashore’.[9]

However, bad behaviour could lead to undesired consequences which impacted on other sailors, not only aboard their own ship but also in harbour. Dennis recorded one such case where men from HMS Black Prince caused trouble outside the Governor of Gibraltar’s residence which resulted in shore leave being cancelled for all ships in port and the Black Prince being given orders to sail.[10] Dennis was therefore naturally relieved when two weeks later ‘all night leave’ was granted and noted it was ‘much appreciated’.[11] Nevertheless, after this, naval commanders were evidently at pains to try and calm crews before they went ashore and captains ‘advised everyone to uphold the reputation and the good name of the ship ashore.’[12]

On the other hand, it is clear that not all sailors conformed to this stereotype and a number of diaries dispel the image of drunken sailors ashore, demonstrating the dangers of accepting stereotypes too readily. Edwin Fletcher’s diaries, for example, reveal that leave for him meant home to his wife and young daughter. He recorded: ‘I met my Darling Wife at Fratton, getting home about 6pm. I enjoyed myself immensely. Time seemed to fly…’[13] Similarly others such as Dennis do not record engaging in any drunken antics either, although their silence does not automatically mean they did not. Instead they recorded what happened to others ashore and are maybe simply reporting those that were causes celebres.

Therefore accepting the stereotype of Jack Tar, as with all stereotypes, is fraught with danger. Whilst some sailors evidently caused trouble ashore others did not and it would be grossly unfair to suggest the stereotype is accurate. Although this article has not had the time to consider the topic in-depth it can nevertheless be argued that these were men who lived a disciplined life afloat and needed time to experience some freedom. The war heightened this as opportunities for leave decreased and the stress of war took hold. It was crucial that sailors had some time to themselves to relax and have some fun; this was an important part of coping with life in the war-time navy.[14] Living with the constant fear of death undoubtedly had an effect upon sailors. It is hardly surprising, therefore, that given the opportunity they enjoyed themselves as much as possible.

References

[1] For example See Mary A. Conley, From Jack Tar to Union Jack: Representing Naval Manhood in the British Empire, 1870-1918, (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2009); Christopher McKee, Sober Men and True: Sailor Lives in the Royal Navy, 1900-1945, (London: Harvard University Press, 2002).

[2] For more on this line of thought please see other contributions to the Port Towns and Urban Cultures project, in particular the work by Louise Moon.

[3] Henry Baynham, Men from the Dreadnoughts, (London: Hutchinson, 1976), 190.

[4] See for example, “Diary of Walter Dennis, 3 December 1914 and 28 February 1915.” Diary digitalized by McMaster University, Ontario Canada and available at http://pw20c.mcmaster.ca

[5] “Diary of Walter Dennis,” 8 September 1914.

[6] See for example RNM 1980/115: “Diary of Edwin Fletcher”, 9 January 1918; “Diary of Walter Dennis”, 8 September 1914.

[7] McKee, Sober Men and True; Baynham, Men, 191. One sailor who did discuss activities ashore is Stoker Robert Percival; Percival goes into detail about prostitution in Malta in 1912. See RNM 1988/294: “Memoirs of Robert Percival.”

[8] 2Diary of Walter Dennis,” 19 November 1914. RNM 1976/65: “Diary of William Williams,” 26 June 1902.

[9] Baynham, Men, 192.

[10] “Diary of Walter Dennis,” 19 November 1914.

[11] “Diary of Walter Dennis,” 3 December 1914.

[12] “Diary of Walter Dennis,” 29 January 1915.

[13] RNM 1980/115: “Diary of Edwin Fletcher.”

[14] For further information on the effect of war on sailors please see Simon Smith, ‘An intimate history of… sailors, killing and death in the First World’, (April 2014).

Hi, I totally agree with you that we need to be cautious with such stereotypes. It was interesting to find similarities and links between your research and what I have found when I have been reading memory writings from former Finnish sailors, who worked on merchant ships at the end of the 19th c. and beginning of the 20th (the memory writings were collected in the 1960s).

I found that there was a shared understanding about how sailors, who, like you said, on board lead a disciplined, simple and even dangerous life, deserved and understandably wanted to relax and enjoy themselves once they were in a harbour. Drinking and other stereotypical sailor behaviour were considered to be some of the attributes of a “real” sailor’s life as well as being part of the initiation rites that beginners and young sailors had to go trough.

However, I also found that there were many respondents who wanted to distance themselves from this stereotypical image. This was done by explicitly underlining their own sobriety or presenting trying alcohol as something that happened at the beginning of their careers, or, when they talked about drinking etc., it was always done by other people. Some respondent also saw excessive use of alcohol as a sign of weakness.

But the problem I face in interpreting these responses is the nature of the sources as memory writings written, usually, several decades later. One of the big questions I have been dealing with is how did the sailors’ attitudes and perspectives change 1) as they got older, educated themselves and became officers as well as got married, and 2) by the time they were writing their memories down.

Hello Laika, can I just say I really enjoyed your contribution to the website. Your work sounds very interesting.

I think you are quite right in saying that many sailors also wanted to distance themselves from the stereotypical image (although others noticeably played up to it too). I mentioned in the article a disturbance caused by one particular ship whilst ashore – in fact it was blamed on a party of stokers from that ship and stokers were regularly viewed as the more “wild” element of the crew and different to sailors. I also agree that often sailors discuss others being drunk rather than talking about their own exploits ashore and this is a good point to make.

Have you any thoughts on the impact of religion on this? I have noticed that some of the Methodist sailors were less likely to discuss drink etc. in their diaries (obviously temperance was a big part of their religious doctrine).

Your two questions are obviously very challenging. One of the nice things about the diaries I have looked at is that they are written up either the same day or within the next few days after the event – although their perspective may change over a day or so if they have time to reflect on events. However I have looked at several diaries over a long career in the navy and it is interesting to see whether their opinions change over the course of their service. I haven’t followed that many through so can’t really comment on this but certainly with the wartime diaries I have looked at you sense them growing older and their attitude changing.

Thank you, that’s nice to hear, and, likewise, your research also sounds very interesting and I think it can be very fruitful to compare the experiences of sailors from different countries.

I think you are right in bringing up religion, in my sources I do not have many men who explicitly write about their relationship to religion or state being very religious but at least generally it seems that sailors who were religious were considered to be a bit different in their attitudes and that this was respected. I have one respondent who describes his stay in a sailor’s home in Norway and praise, among other things, the religious practices of the home. He states that after this experience he never wanted go and live in a bar again. I feel that it is quite hard to try and estimate how religious, for example, an average working-class person was at that time and I definitely need to read more previous research about that. One point which I have been pondering is how much sailors in a way internalised the messages that the Mission, the media or the sailor’s homes represented especially as they got older and how much they then reproduced (or thought they had to reproduce) in their own writings.

The diaries you are using must be a wonderful source! This summer I am going to explore if some sailor diaries have also survived here in Finland. Do you know whether your sailors were just writing the diaries for themselves or did they have other aims or purposes for them? I have some respondents who continued working on merchant ships during the war and who tell stories about the dangerous situations they encountered during the war (some even ended up in war camps) but obviously their situation was nothing compared to the men working on actual war ships as in you case. The war must have really changed the general atmosphere onboard as well as personal attitudes.

When I was in a “quiet run” was the primary objective. You aimed to specifically avoid the hot spots.

After the first night’s runs the buzz would tear round the ship that, say, Maria’s in the old town was the place for the action.

Adherents to the quiet run school marked down Maria’s as the place to avoid.

Trouble? Yes, it happened, and in my experience was always linked to having just a little too much to drink.

My grandfather Joseph Parker was in the Royal Navy all through WW1 and kept a brief note of the places he had served (Antwerp, Gallipoli, Alexandria, DAMS gunner). Between 1914 and 1919 he records 6 periods of leave. Sep14 – 7 days after Antwerp; Jan15 – 7 days at New Year in Scotland; 28 days in Jun18 in England – met his future wife at his old employers; Oct18 – 4 days in Cardiff; Nov18 – day “outing to Naples”; Jan19 – 10 days in Middlesbrough, before discharged. His service record shows what his diary does not mention, ““sentenced to 5 days cells … used insulting language to Section Leader” in Port Said. Otherwise, his service record is “VG”.