Following on in similar vein to my recent article on sailors in the Royal Navy during the First World War, this article will expand upon sailors’ attitudes to killing and death in the Great War by considering their diaries. At this juncture it is worth revisiting Joanna Bourke’s interesting study: An Intimate History of Killing.[i] In this study Bourke wiped away the romanticized gloss of warfare and examined instead the brutalities inherent in war. As she posited, ‘the characteristic act of men at war is not dying, it is killing.’[ii] Although sailors were rarely face to face with their enemy they too killed when necessary. Furthermore, as Bourke has argued, distance did not remove the intimacies of killing.[iii] For example gunners could see the damage their shells inflicted on their enemy and their imaginations could easily fill in the blanks.

Following on in similar vein to my recent article on sailors in the Royal Navy during the First World War, this article will expand upon sailors’ attitudes to killing and death in the Great War by considering their diaries. At this juncture it is worth revisiting Joanna Bourke’s interesting study: An Intimate History of Killing.[i] In this study Bourke wiped away the romanticized gloss of warfare and examined instead the brutalities inherent in war. As she posited, ‘the characteristic act of men at war is not dying, it is killing.’[ii] Although sailors were rarely face to face with their enemy they too killed when necessary. Furthermore, as Bourke has argued, distance did not remove the intimacies of killing.[iii] For example gunners could see the damage their shells inflicted on their enemy and their imaginations could easily fill in the blanks.

The act of ‘blood-letting’, Bourke has argued, was an integral part of military life and proved a recurrent theme in letters and diaries.[iv] The extent to which this can be applied to sailors, however, needs further consideration. Sailor diaries do not provide particularly fertile grounds for exaggerated, gory descriptions of battle.[v] In keeping with the brief and perfunctory nature of personal logs, naval engagements were often carefully recorded in meticulous detail but the level of description and personal views entered was very much dependent upon the writer.[vi] Edwin Fletcher, for example, noted at Jutland,

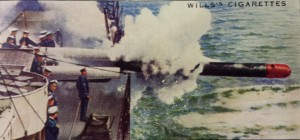

On the other hand Seaman Wood indicted a more relaxed view on the death of enemy troops, as he watched ships shelling forts at the Dardanelles he noted it was ‘amusing to see the Turks nipping out of the way’.[viii] Similarly Walter Dennis described firing ‘a perfect hail of shrapnel’ and the damage it caused to Turkish forts ashore.[ix]

The importance of recounting experiences and telling war stories has been highlighted by Bourke, as men who did not exhibit ‘an active warrior attitude’ were at risk of having their ‘status and virility’ doubted.[x] Even those who had not seen action eagerly picked up stories, often fabricated, to assert their manliness.[xi] Second-hand stories evidently were passed around by sailors as demonstrated by Walter Dennis who regaled a tale about the corpse of a Marine found ashore ‘terribly mutilated, the head smashed, and the stomach & legs hacked about, probably some result of German teaching in Kultur.’[xii] Yet he does not claim ownership and this is not an attempt to assert his manliness. However, Bourke consequently argued this was the reason for the popularity of taking souvenirs, describing a ‘flourishing trade’ in curios taken home to ‘bolster wild stories that they told their loved ones’.[xiii] Sailors may not have had such rich pickings as their brothers in khaki ashore, but Wood of HMS Ark Royal recorded picking up a piece of shrapnel from a German bombing raid ‘for a curio’, along with many other crew members.[xiv] Walter Dennis also recorded shrapnel from a Turkish shell being picked up from the deck by sailors eager for ‘curios’.[xv]

To conclude, this article has not sought to be a direct comparison between soldiers and sailors but rather to demonstrate salient points raised by Bourke and put sailors into the narrative. Although sailors were commonly removed from intimate face-to-face combat, killing was a necessary part of life during the war. Although their diaries do not exhibit gory incidents of killing, its importance to them is evidenced by their detailed records of injury, death and damage that they caused. By applying Bourke’s study to this topic it has demonstrated the parallels extant between sailors and soldiers during war and the need for further consideration.

References

[i] See Joanna Bourke, An Intimate History of Killing: face-to-face killing in twentieth-century warfare, (London: Granta Books, 1999).

[ii] Bourke, Intimate, 1.

[iii] Bourke, Intimate, 7.

[iv] Bourke, Intimate, 3.

[v] Although letters are yet to be fully considered.

[vi] Sailors would amend entries as more information became available to them. For more information see RNM 1980/115: Diary of Edwin Fletcher and RNM 1984/467: Diary of Seaman Wood. Sailors would amend entries as more information became available to them.

[vii] RNM 1980/115: Diary of Edwin Fletcher, 31 May 1916.

[viii] RNM 1984/467: Diary of Seaman Wood, 7.

[ix] Diary of Walter Dennis, 2 May 1915.

[x] Bourke, Intimate, 36.

[xi] Bourke, Intimate, 34.

[xii] Diary of Walter Dennis, 26 February 1915. ‘Kultur’ underlined by the author.

[xiii] Bourke, Intimate, 34.

[xiv] RNM 1984/467: Diary of Seaman Wood, 13.

[xv] Diary of Walter Dennis, HMS Vengeance, 1914-1915, 19 February 1915.

Comments are closed.