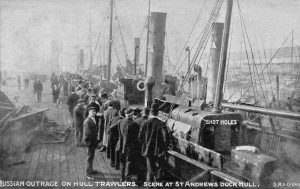

Though historians have begun to reassess the extent of anti-German feeling in Britain in the years preceding the outbreak of the First World War, it is nevertheless interesting to take note of an incident where a Russian naval blunder became the site of Anglo-German antagonism.[1] Taking place in the thick of the Russo-Japanese War, the event that became known as the ‘North Sea (or Russian) Outrage’ occurred on the night of 21-22 October 1904, when elements of the Russian Baltic Fleet at Dogger Bank fired upon unarmed trawlers from the port of Hull, after apparently mistaking them for Japanese torpedo boats.[2] The incident triggered a diplomatic crisis and temporarily threatened relations with Britain and Russia. A Times correspondent described the feeling in Hull following the events: ‘Undeniably there is great indignation here; but the people are not excited; and, so far as I can judge from several conversations with persons of different classes, the predominant feeling is bewilderment, mingled with anxiety for the rest of the fleet’.[3]

The burial service of two men killed aboard the Crane occasioned scenes of public mourning across the city, with flags on civic buildings and aboard ships in the docks flying at half-mast. Tens of thousands of people were reported to have thronged the route of the cortege, passing primarily through the Hessle Road fishing district in the West of the city. The Hull press underlined the event’s importance for local identity: ‘The scene will not only live in memory: it will live in history, local history at least’. The funeral ‘spectators’:

… felt they were taking part in an event which the whole country was viewing. Their gathering together was more than an expression of deep and profound sorrow; it was a demonstration the true inwardness of which was all the more apparent because of the very dumbness of it.[4]

Here, the self-contained and independent character of the fishing district was emphasised, its mass grief concentrated in a specific area adding an especially sombre mood to proceedings. Similar scenes were reported in other regional fishing centres, including Grimsby, where ‘great indignation was expressed by all hands’ at the dockside.[5] Local newspapers ranged between outrage, ambivalence and disbelief. The Beverley Recorder struggled to reconcile Hull’s longstanding maritime connections with such an offensive action:

Russia was, perhaps, less badly beloved in Hull last week end than anywhere else in the United Kingdom, because of intimate business relationships; but the inhabitants of the Humber port have been wounded sorely through wanton recklessness now, and the wounds will rankle for many a year to come.[6]

But these longstanding connections did not prevent an outpouring of editorial Social Darwinism comparable to what many newspapers would continually reproduce with reference to Germans during the First World War:

The Muscovite needs so very little scratching to discover his Tartar origination. He manifests such a traditional facility for doing outrageous things, and saying he is sorry if brought to book. He will promise to make such amends as may be, undertake never to offend again, and straightaway proceed to re-enact the whole farcical tragedy there or elsewhere.[7]

Here Russian people, or at least naval men, are racialised or ‘Othered’ in a way that allowed British audiences to make sense of the event, belying its complexities.[8] Such ideas maintained a currency during the early months of First World War, with the Hull Daily Mail reporting in October 1914 that a captured ‘enemy alien’, trawler skipper George Volson, had eschewed his Russian lineage by signing on to his vessel as a German. In the face of anti-alien legislation he went on to assert his Russian nationality.[9] Some speculated that the Russian sailors must have been drunk or possibly suffering from a ‘dangerous delirium’.[10] Others simply questioned the competence of the Baltic Fleet men, tacitly implying the steadfastness of British sailors in comparison:

They are not the best or most seasoned men in the Russian navy… They are “a scratch pack of more or less incompetent people who are navigating a still more incompetent fleet to almost certain destruction – and they know it. Small wonder, then, if their nerves are not as they should be, and if they are prepared to see a foe in every foreign funnel, as children fear a ghost in every dark room.”[11]

Some German officials at this time, including Kaiser Wilhelm, harboured a secret wish for the weakening of Russian relations with Britain, in the hope that the latter would eventually lose a strong commercial and naval ally. Hence the initial glee displayed by the Kaiser in secret correspondence at the mistaken sinking of the British trawling vessels.[12] Some in the press began to assert that Germany was behind the Russian action, or at least that she had something to gain from the ensuing political situation. As Credland notes, this could have included the hope of a German-Russian alliance at the expense of Britain and France, though this never came to pass.[13] A report on ‘German views of Anglo-Russian relations’ appeared to underline the desire among some of the higher echelons of German government and military command to drive a wedge between the two nations. Quoted in The Times, the National-Zeitung claimed that England, along with France, actively sought the isolation of Germany, not least through naval dominance. This was the context of Germany’s increasingly visible attempt to rival British sea power through the accelerated building of war vessels. Indeed, Germany increased naval spending considerably during 1904-6, though this still clearly lagged behind the vast sums expended by Britain.[14]

The Hull Daily Mail reported with disdain the words of a Prussian politician as to the collusion of Britain in the ‘Dogger Bank affair’:

The amazing lengths to which Anglophobism [sic] can be carried in Germany is illustrated by the assertion that Great Britain planned a sudden attack on Germany at the time of the Dogger Bank affair without any formal declaration of war.[15]

This was a statement made some five years after the event, amid fears of a German challenge to British naval supremacy. It is therefore probable that the ‘echoes’ of Dogger Bank in 1909 combined well with looming concerns that Britain’s imperial dominance was vulnerable to a rising German power. Viewed numerically, we can see that such fears were not entirely without cause, as Britain and Germany possessed fifteen and twelve battleships and battle cruisers respectively by this point.[16]

An article reporting ‘German Anglophobia’, published only one year after the incident, posited Britain’s ‘Machiavellian role’ in attempting to isolate Germany, the subtext suggesting that Germany had much to gain by threatening Anglo-Russian relations.[17] The most commonly-debated topic in this period was compensation for the victims the ‘North Sea Outrage’, including not only widows and family members but fishing fleets who had to repair damaged vessels and fishing gear, and recoup business losses. However, this did not stop some commentators from shifting focus on to German diplomatic and public opinion, when one would expect Russia to be bearing the full emotional and ideological brunt of post-incident feeling.[18] Despite public indignation, a more conciliatory approach is palpable at this time, as the British government sought to assuage fears of social upheaval in Russia, a situation that could destabilise the whole of Europe.[19] Indeed, as soon as 28 October, the Hull liberal press was confident enough to state that the ‘war cloud’ had lifted, blaming the Northcliffe ‘Jingo’ press for exaggerating fears of possible a European conflagration. This positive note was tempered by expressions of gratitude to France for her conduct during the conflict, with Germany’s role conspicuous for its absence.[20]

In 1907, Britain and Russia formally codified their economic and imperial relations. Détente led to entente and the two nations fought together against Imperial Germany during the First World War, showing to some extent that the ‘outrage’ of 1904 had less long-lasting effects in terms of diplomatic and political relations than the localised, popular memory of the event would have for maritime communities.[21] This is still very much the case today, as local history and fishing heritage groups still revisit the fateful events of 21-22 October 1904 through commemorative publications and memorial events. The longstanding maritime links of trade and fishery played a focal role in expressions of international solidarity during the First World War, particularly as part of fundraising efforts.[22] It seems that the political expediency of anti-Germanism at particular points during the early years of the twentieth century explains why an ‘outrage’ perpetrated by Russian naval vessels, during a war between Russia and Japan, could become the focus of Anglo-German conflict. As we have seen, this was particularly the case during periods of German naval advancement, amid fears that British sea power could be eclipsed by German efforts.

Notes

[1] Jan Ruger, ‘Revisiting the Anglo-German Antagonism’, Journal of Modern History, vol. 83, no. 3, (2011), 579-617.

[2] Michael Epkenhans, ‘Was a Peaceful Outcome Thinkable? The Naval Race before 1914’ in An Improbable War? The Outbreak of World War I and European Political Culture Before 1914, eds. Holger Afflerbach and David Stevenson (New York: Berghahn, 2007), 119.

[3] ‘The Feeling in Hull’, The Times, 25 October 1904, 7.

[4] ‘A City’s Grief’, Eastern Morning News, 28 October 1904, 5.

[5] ‘Feeling at Grimsby’, Eastern Morning News, 25 October 1904, 6.

[6] ‘Stray Notes’, Beverley Recorder, 29 October 1904, 4.

[7] Editorial, Beverley Recorder, 29 October 1904, 4.

[8] Adrian Gregory, The Last Great War: British Society and the First World War (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2008), 59.

[9] ‘Aliens at Grimsby’, Hull Daily Mail, 8 October 1914, 5.

[10] ‘The Continent Supports Us’, Eastern Morning News, 26 October 1904, 4.

[11] Editorial, Eastern Morning News, 25 October 1904, 4. Quotation marks in original.

[12] Paul M. Kennedy, The Rise of the Anglo-German Antagonism 1860-1914 (New York: Humanity Books, 1980), 271.

[13] Arthur G. Credland, North Sea Incident, 21-22 October 1904 (Hull: Hull Museums and Galleries, 2004), 45.

[14] Table 6.1, cited in Epkenhans, 127; John Brooks, ‘Dreadnought: Blunder or Stroke of Genius?’, War in History, vol. 14, no. 2, (2007), 169.

[15] ‘Dogger Bank Echo’, Hull Daily Mail, 8 November 1909, 4.

[16] Table 6.2 in Ibid.; Ibid., 121.

[17] ‘German Anglophobia’, Yorkshire Post, 30 November 1905, 7.

[18] Credland, 44; ‘The North Sea Outrage: Assessment and Division of the Compensation Claims’, Yorkshire Post, 25 March 1905, 9.

[19] Credland, 43.

[20] ‘The Lifting of the War Cloud’, Eastern Morning News, 28 October 1904, 4.

[21] Friedrich Kießling, ‘Unfought Wars: The Effect of Détente before World War I’ in An Improbable War? The Outbreak of World War I and European Political Culture Before 1914, eds. Holger Afflerbach and David Stevenson (New York: Berghahn, 2007), 190.

[22] See my earlier PTUC article: http://porttowns.port.ac.uk/transcending-space/.

Comments are closed.