The program of online digitisation of books and documents is now permitting new insights into the global reach of East India Company (EI Co) networks.[1] EI Co servants such as the Supercargoes based at Macau and Canton played a critical role in the regional bullion trade and some of their other previously unknown business ventures which were until now little known, such as Pacific whaling, is becoming evident.

Moreover, their involvement in the development of the maritime fur trade of the Northwest coast of America (Nootka) from India and China has raised new questions on merchant collaborations. Crucially, the flagging of ships that allowed ‘private’ ventures in trade to be undertaken from Asia in spite of the East India Company monopoly in the Pacific. Indeed, it was this group of merchants who were among the founders of the British Southern Whale Fishery in the Pacific.

The Fitzhugh family were hugely important through their Manila bullion partners (Locatelli) and their dealings with the Royal Philippine Company London agent Fermin de Tastet.[2] William Fitzhugh and William Henry Pigou (a Huguenot and Chief of the Canton Council c. 1784) were also involved in the silver bullion trade with Madras ‘factors’ to Canton, against ‘bills’ to London (less shipping and commission).[3] These two were both also engaged in early Pacific whaling ventures organised from Asia via London associates and by merchant Alexander Tennant at the Cape of Good Hope.[4] London Merchants, in particular Camden, Calvert & King, were keenly aware of the usefulness of ‘flagging’ ships under neutral colours and were associates of the Fitzhugh family.

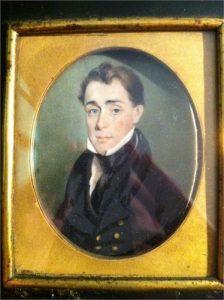

Alexander Tennant, merchant of the Cape of Good Hope and Partner and associate of Captain Hogan and Anthony Calvert of Camden, Calvert & King, London merchants (Private Collection).

Camden, Calvert & King’s connections via other India-based merchants such as David Scott and his business partner William Fairlie and their networks with the merchant Duntzfeltz in Hamburg and James Scott (a nephew of David Scott) in Penang, plus the Manila connections of the Fitzhughs have until now have been obscure. The Fitzhugh family’s role in bullion dealings, both regionally and globally, are now much clearer now that new documents have become available online.[5] Such was their success that by the late 1770s William and Thomas Fitzhugh were also large British government loan contractors in London in their own right.[6]

Agents such as Robert Charnock, based in Ostend, also played a critical role in the flagging of ships for merchants such as Camden, Calvert & King. Services were also provided to other ship owners in the Nootka maritime fur trade. James Cox was another merchant who was keen to develop his Asian business enterprises, particularly in respect of the Nootka fur trade. Significantly, the Cox family were also partners in Cox & Merle, Bullion Dealers of 2, Cox’s Court, Little Britain. In addition to fur and bullion, John Henry Cox, was sponsored by Joäo de Carvalho, a Macao Portuguese, to develop slave trading activities from Goa via Mozambique to the Cape and Brazil. This diversification has been noted by Christopher Ebert who argued that

It was probably British merchants who were otherwise ‘shut out’ of Brazilian trade who attempted this commerce, for there were structural impediments to contraband trade … it was British trade with Portugal, not primarily with Brazil, that created the current account surpluses that necessitated payments to Britain of Brazilian gold. Also, British merchants in Lisbon profited from sending their manufactures to Brazil legitimately, and they were invested in the trade under cover of Portuguese partners. Finally, they were well aware how easily Brazilian markets for British exports could be saturated, in spite of increasing prosperity and population there. Consequently the British factory opposed direct trading by merchants of any nation, including their own. British merchant interests were not monolithic, and some might try to trade illegally in Brazil, but powerful British merchant groups, with support from two crowns, were arrayed against them.[7]

Another prominent figure in the fur trade was Daniel Beale (1759–1842) a Scottish merchant active in the Far East mercantile centres of Bombay, Canton and Macau as well as at one time being the Prussian Consul in China. Another Scottish merchant in Canton in the late eighteenth century was John Reid (c.1757 – 11 April 1821) who was in partnership with John Henry Cox and Daniel Beale. In 1779 he was in Canton acting as the Austrian Emperor’s Consul. William Bolts, who was Consul for the Imperial Company of Trieste and Antwerp, had Reid acting as his agent at Canton.[8]

These Asian networks, which included Camden, Calvert & King, were very fluid and their operations had a global reach.[9] What is striking is the level at which that these groups operated at with Huguenot insurance and banking connections closely allied to the East and West India trades. London merchant Peter Thellusson and partner Sir William Curtis were shipowners and insurers of vessels on a global scale. Curtis, a member of the Dundee Arms Freemasonry Lodge in Wapping, and Charles Lindgren, an important EI Co Coastal Agent for Portsmouth, was also a member of this influential social network. The group were able to strategically place correspondents throughout the world that operated with a large degree of autonomous sophistication.[10]

Recent research has highlighted how influential Scots in the East and West Indies influenced trade both regionally and internationally. It was their adaptability and responsiveness to changing local conditions that insured success for their sponsors, patrons and partners based overseas, particularly those operating in London. IN addition, new and exciting research is being undertaken by scholars such as Ander Permanyer-Ugartemendia and Jesus Bohorquez Barrera.[11] Both are currently investigating the links between Spanish and Portuguese merchants in Portuguese Africa, India, Macao and China and how they interacted with British merchants of the EI Co such as the Fitzhughs to supply Spanish America with slaves. We are entering into a far greater understanding of just how global this history really was and just how far the Scottish and Huguenot linkages reached into under-researched geographic areas.

Further reading:

Bolts, William. A Dutch Adventurer under the John Company, (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1920).

Everaert, John, “Willem Bolts: India Regained and Lost: Indiamen, Imperial Factories and Country Trade (1775-1785)”, in Mariners, Merchants, and Oceans: Studies in Maritime History ed. K. S. Mathew, (New Delhi: Manohar, 1995), 363-369.

Gough, Barry M. and Robert J. King, “William Bolts: An Eighteenth Century Merchant Adventurer”, Archives: The Journal of the British Records Association xxxi, no.112 (2005): 8–28.

Reidy, Michael. The Admission of slaves and ‘Prize Slaves’ into the Cape Colony, 1797-1818. Unpublished MA Thesis (Cape Town: University of Cape Town, 1997). This thesis discussed the East India slave trade which Tennant, Trail & Hogan were involved with.

Tomlinson, B. R. “From Campsie to Kedgeree: Scottish Enterprise, Asian Trade and the Company Raj,” Modern Asia Studies 36, Issue 4 (2002):769-791.

Wanner, Michael, “The Imperial Asiatic Company in Trieste—The Last Attempt of the Habsburg Monarchy to Penetrate East Indian Trade, 1781-1785”, 5th International Congress of Maritime History, Royal Naval College, Greenwich, 23–27 June 2008.

Notes:

[1] Google Books, Google Scholar and Gale Publications/Databases all provide extensive online provision for the academic researcher of many eighteenth century primary resources.

[2] Thomas and William were EI Co Supercargoes who sat on the Canton Select Committee. See: Terrick V.H. FitzHugh & Henry A. Fitzhugh, The history of the FitzHugh family in two volumes, Ottershaw: Privately printed by Terrick V. H FitzHugh, Ottershaw, 1998). See too: A. Permanyer-Ugartemendia, “The Spanish link in the Canton trade, 1787-1830: silver, opium and the Royal Philippine Company” available via Academia.edu http://upf.academia.edu/AnderPermanyer

[3] See: Ken Cozens, “East London merchant networks in Asia: the Fitzhughs 1750-1800, East India Company Agents in Macao” ‘The Lure of the East. European Seafaring Beyond Suez’, 41st University of Exeter Maritime History Conference, 2007, Available on the authors Academia.edu webpage: http://gre.academia.edu/KennethCozens

[4] See: Hull University’s British Southern Whale Fishery voyage database available at Dale Chatwin’s British Southern Whale Fishery website: http://www.britishwhaling.org/). Ship Roman Emperor, was registered as owned by Fitzhugh in 1787. It was recorded to be carrying 103 tuns of whale oil plus 90 cwt of bone and 3000 seal skins. Registered owner in 1789 is listed as Pigou).

[5] As part of the global bullion trade Spanish American bullion was being transported by the British through the contracts of Gordon & Murphy in Jamaica and Cadiz. See: Franklin W. Knight, Peggy K. Liss, Atlantic Port Cities: Economy, Culture, and Society in the Atlantic World. (Knoxville: University of Tennessee Press, 1991) and Adrian Pearce, British Trade with Spanish America, 1763-1808. (Liverpool: Liverpool University Press, 2007). Silver and gold were critical for trade with the Chinese at Canton and shortage of it was sometimes a problem for the British, hence the Fitzhugh dealings with the Royal Philippine Company in Manila.

[6] Cozens, “East London merchant networks”.

[7] Christopher Ebert, “From Gold to Manioc: Contraband Trade in Brazil during the Golden Age, 1700 1750,” Colonial Latin American Review 20, issue 1 (2011): 109-130.

[8] William Bolts, A Dutch Adventurer under the John Company, (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1920).

[9] For a greater understanding of East India Company Directors and their networks see: J. G. Parker, The Directors of the East India Company, 1754 – 1790. Unpublished PhD Thesis (Edinburgh: University of Edinburgh, 1977) for example information on Charles Murray, (later Madeira Consul) in 1765. He was in his early thirties and employed by Scott, Pringle, Cheap & Co. of London and Madeira, partners of the firm were also scions of old Scottish Borders families and associates of Camden, Calvert & King in London. It was while Murray was a wine merchant that he travelled through the colonies. This journey through Britain’s North American possessions, making contacts and cementing networks, which was a standard part of the career of young Madeira merchants. Thomas Cheap, was an East India Company Director with the Madeira wine contract to supply India. John Pringle was a EI Co factor with connections at the Cape of Good Hope and an associate of Camden, Calvert & King’s partner in India David Scott. See: Grant Samkin, “Trader sailor spy: The case of John Pringle and the transfer of accounting technology to the Cape of Good Hope,” Accounting History 15 issue 4, (2010): 505-528.

[10] Gary L. Sturgess & Ken Cozens, “Managing a Global Enterprise in the Eighteenth Century: Anthony Calvert of The Crescent, London, 1777–1808”, The Mariner’s Mirror 99, issue 2 (2013): 171-195.

[11] Ander Permanyer Ugartemendia’s Academia webpage for details of his research into Spanish merchant networks in Asia: http://upf.academia.edu/AnderPermanyer. See also Jesus Bohorquez Barrera. See: His Academia.edu webpage for some papers: http://harvard.academia.edu/jbohorquez

His paper “Between Calcutta and London: Asian Textiles and British Capital in the Financing of the Portuguese South Atlantic Slave Trade (1790-1811)” and his thesis Globalizing the South. The Rise of Global Cities and the Political Economy of the Portuguese and Spanish Empires: Rio de Janeiro and Havana during the Age of Revolutions, were kindly made available to the author.

Very impressive research, Ken – I’m finding more and more connections to my puzzle – I began reading Dan Byrne back in the 1980’s. In short, where you are mostly following the economic-mercantile trail I’m trying to put together the ‘fraternal brotherhood’ trail, including Freemasonry of course, but not only – Lord Nelson, for example, was a member of the Ancient Society of Gregorians (see Downer). Freemasonry was/is not special, its Grand Lodge attached itself, via the Hughenots I believe, to the Walpole Govt (see Berman) and became viscerally connected to the Court and administrations up till the end of the Napoleonic Wars at least. Then, its role was taken over by arms of govt but it, Freems, cd not survive without Royal patronage.

Anyway, best I’d like to keep in touch. Cheers (Dr) Bob James.

Hello – is there any biog detail of ‘Thomas King’ of C,C & K before he met Calvert? Is there any chance this King has connections to the Phillip Gidley King, 3rd Gov of NSW?

Love your work. Cheers Bob James