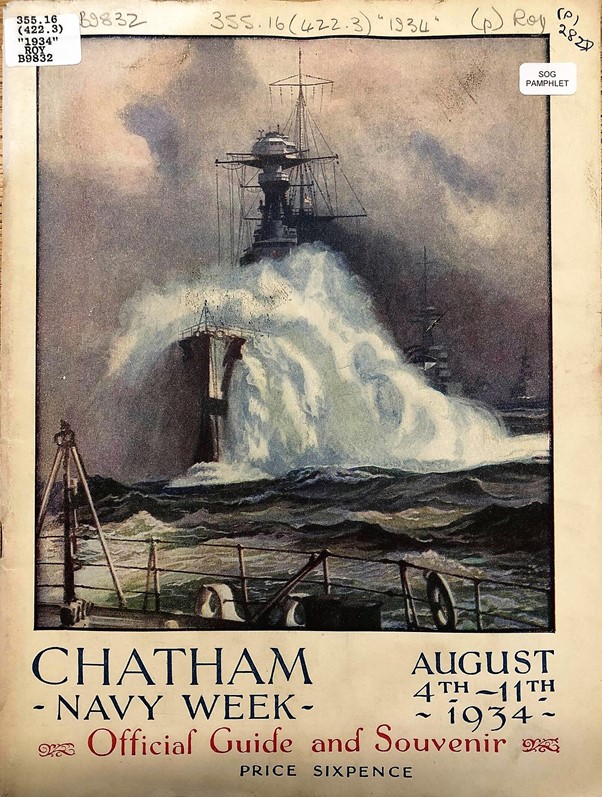

National Maritime Museum, Greenwich, London, PBB9832: Chatham Navy Week: Official Guide and Souvenir, 1934. Courtesy of the National Maritime Museum, Greenwich, London.

In August 1927, nearly 50,000 people flocked to Portsmouth to attend the first Navy Week. Showcasing the power and prestige of the Royal Navy, battleships, cruisers, destroyers, mine-laying monitors, submarines, and an aircraft carrier were all either on view or available for close inspection. Attendees saw HMS Rodney and HMS Nelson, the two most modern and powerful battleships in the world, and were able to examine HMS Hood, the largest, heaviest, and fastest warship for its size in the world for much of its existence.[1] While the ‘towering steel walls’ and ‘wonders of the giant warships’ attracted much interest at Navy Weeks, so too did the recently restored HMS Victory, Admiral Horatio Nelson’s flagship at the Battle of Trafalgar.[2] The annual celebration of Navy Weeks demonstrates that popular, cultural, and symbolic manifestations of the ‘cult of the navy’ still undoubtedly had resonance in a period of supposed naval decline and hostility towards militarism.[3]

Navy Weeks represented a ‘naval theatre’ where ‘tradition, power and claims to the sea were demonstrated to both domestic and foreign audiences’.[4] The event’s origins can be traced to the annual Trafalgar Orphan Fund procession pageants and flag days, which were held in Portsmouth from 1920. The Fund’s purpose was to raise money for orphans of naval men who had lost their lives in the First World War. Yet, many felt that the spectacle of the Navy annually appealing for funds by pageants and flag days was unworthy of the Senior Service. Navy Weeks were a far less objectionable method of raising money. First staged as an ‘experiment’ at Portsmouth, then extended to Plymouth and Chatham the following year, Navy Weeks were held between 1927–1938 and allowed members of the public to be brought into direct touch with the work and life of the Royal Navy.[5]

Raising funds for naval charities was the publicly stated aim of Navy Weeks. However, the event was also an important platform for the Admiralty and key naval figures to promote the navy’s centrality for the preservation of Britain’s status as an island nation and the maintenance of empire. Organisers attempted to construct (and project) local, national, and imperial identity through the event, alongside encouraging naval education among the British public more broadly. The propagandistic and educational value of the annual event was certainly clear. As one reporter claimed, by visiting Navy Weeks ‘any member of the public can find out more about the Navy in a few hours than could be discovered by reading every book on naval matters which has ever been written’.[6]

Visitors at Navy Weeks saw naval exhibitions, art displays, the changing of the guard, naval pageants, and could even listen to sea shanties such as Shenandoah, Billy Boy, Blow the Man Down, Bound for the Rio Grande, and the Song of the Jolly Roger.[7] These displays were an important way of drawing on the customs, heritage, and tradition of the Royal Navy. Yet, Navy Weeks were also characterised by modernity and technological innovation. Attendees saw the ‘gigantic floating fortresses of the British Navy’, alongside a range of modern, martial, and militaristic naval spectacles.[8] First World War re-enactments, searchlight displays, night action demonstrations, mock coastal bombardments, aeroplane attacks on cruisers and battleships, gas and air raid precautions displays, and the recapturing of ‘pirate’ steamers were just some of the visually impressive set-pieces staged. The event’s martial and militaristic nature did attract some criticism, with a range of pacifist, communist, liberal internationalist, and anti-war groups all opposing the event. For many, however, Navy Weeks represented the ‘best shilling’s worth of popular and instructive entertainment in the world’.[9]

Between 1927–1938 Navy Weeks attracted a cumulative total of nearly 3.5 million visitors.[10] While many visitors were based in London or the south of England, large numbers from further afield – facilitated by coach and rail excursions – also attended the annual event.[11] As a local observer put it: ‘One had only to listen to the various dialects to get an idea of the far-pulling power of Navy Week’.[12] According to another newspaper, visitors from the North East in particular were ‘greatly amused by the Southern accent “Aa cannit mak’ oot wat these folks is taakin’ aboot. Whey on orth divvent they speak King’s English?”’[13] Navy Weeks were in fact so popular that the Admiralty and Commanders-in-Chiefs of the home ports contemplated holding similar events in the north of England, Scotland, and Northern Ireland. Ultimately, however, the scheme to expand the event was deemed financially and logistically impractical and so was abandoned.[14] While these initiatives were unsuccessful, London, Glasgow, Bristol, and Southampton all staged their own respective Navy Weeks in the 1930s.

Navy Weeks provided an important source of local and civic pride, but the event also fuelled inter-port rivalry. Commentators reflected on the ‘insular pride’ shown by the three home ports, although suggested that there was no need for such rivalry when ‘each of these ancient naval strongholds has such [a] wealth of historic association’.[15] While each port could justifiably claim to have had an important role in key moments of Britain’s naval (and national) history, observers nevertheless felt that it was ‘not to see where DRAKE played bowls that people come to Plymouth, nor to have a look at the “George Inn” whence NELSON embarked for Trafalgar that they flock into Portsmouth, nor to picture the ships of VAN TROMP banging their culverins up the Medway that they go to Chatham’. Instead, it was ‘power, presented in its latest and most potent forms’ that was reportedly the principal draw for spectators.[16]

At a time of increasing threats to Britain’s navy in the form of disarmament, economic instability, and the growing significance of air power, Navy Week organisers sought to remind audiences that the ‘responsibilities of the Navy have not lessened . . . it is upon the Navy, under the good Providence of God, that “the wealth, safety and strength of the Kingdom chiefly depend.”’[17]

Notes

The author gratefully acknowledges the Institute of Historical Research and the Social History Society for supporting this research.

[1] Ralph Harrington, ‘‘The Mighty Hood’: Navy, Empire, War at Sea and the British National Imagination, 1920–60,’ Journal of Contemporary History, vol. 38, no. 2 (2003), 173.

[2] ‘The World’s Largest Warship,’ The Times, 15 August 1928; ‘“Navy Week” at Three Ports,’ The Daily Telegraph, 30 July 1932.

[3] Jan Rüger, The Great Naval Game: Britain and Germany in the Age of Empire (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2007), 1.

[4] Rüger, The Great Naval Game, 1.

[5] Christopher Bell, The Royal Navy, Seapower and Strategy Between the Wars (Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2000), 174–78.

[6] ‘The Navy at Home,’ The Listener, 05 August 1931.

[7] For example, see ‘The Navy’s “At Home”’ (London: British Pathé, 1933), https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=163eTCb3lO8&t=6s, date last accessed 14 June 2021.

[8] ‘Winchelsea, Nursery of the British Navy,’ Bognor Observer, 17 July 1929.

[9] ‘Navy Week,’ Shipping Wonders of the World, July 1936.

[10] Bell, The Royal Navy, 175.

[11] For example, at Portsmouth Navy Week in 1938, slightly under half of all visitors were from outside London, the Southern Counties, the Isle of Wight, or the Channel Isles. The National Archives (TNA), ADM 179/63, Navy Weeks, 1935–1939, Report on Portsmouth Navy Week 1938, Appendix C.

[12] ‘England Sees the Navy,’ Portsmouth Evening News, 08 August 1935.

[13] ‘Even the Sun Smiled!,’ The Sunderland Echo and Shipping Gazette, 03 August 1936.

[14] TNA, ADM 116/2478, Navy Weeks at Home Ports, 1925–1931, Navy Weeks at Northern Ports, Summary of replies from Commanders-in-Chief etc., 05 May 1931, 1–5.

[15] ‘Navy Week Programmes,’ Truth, 01 August 1934.

[16] ‘Navy Week Opens,’ The Western Morning News, 01 August 1938. Emphasis in original.

[17] Don Leggett, ‘Restoring Victory: Naval Heritage, Identity, and Memory in Interwar Britain,’ Twentieth Century British History, 28, no 1 (2017), 57; National Maritime Museum, PBB9838, Chatham Navy Week Programme, 1933, 7.

Comments are closed.