A Sense of Geography

The Irish Sea is the expanse of water that separates Ireland from Great Britain with the Port of Cork situated at the south western end of the island. Cork Harbour is situated in the centre of the southern seaboard facing south to the Atlantic and its natural harbour became an important port of call for Atlantic shipping and the natural exit for southern agricultural exports.

By the seventeenth century English involvement in the New World created opportunities for the Port of Cork to nurture a provisions trade. Cork was seen as a distribution centre for its hinterland products rather than a “classic entrepôt specialising in a redistribution of colonial goods by trans-shipment.”[1] Cork prospered as a centre of the provisions trade supplying the Fleet and eventually the Colonies. However, the city failed to industrialise during the period of the Industrial Revolution as it did not have coal or iron ore trade, nor did it have any administrative centre of consequence. It relied instead on its harbour and hinterland for economic momentum.

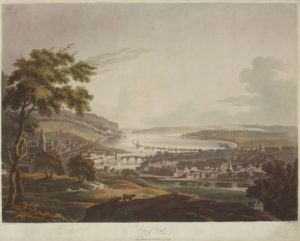

Cork Port in 1800

In 1800 Cork Port was unregulated as regards shipping activities and had no port authority structure. The port was under the control of Cork Corporation, the municipal authority, in terms of financing, investment and shipping matters. The corporation had benefitted from the growing incomes of a prosperous city with revenues increasing from £900 in 1715 to about £1,200 by 1732 and had reached £7,000 by 1820.[2]

The port was in a poor state of maintenance and lack local authority investment meant that there was an urgent need to improve and invest in its infrastructure.[3] In 1813, only small vessels drawing 11 feet of water enter Cork city during high water and on berthing at Cork had to be aground on a gravel bottom to discharge. The lower harbour was only three feet deep in places and large vessels had to unload cargo onto lighters. All of this added to the time and cost of vessels visiting the port. [4]

A Harbour Authority – Cork Harbour Commissioners

A first step to improve the port’s infrastructure was the passing of the Butter Weighhouse Act (1813) under which commissioners were appointed to improve the ‘harbour and river of Cork’.[5] Significantly, twenty-one merchants of the city were appointed as commissioners. One third of the fees received by the Weighmaster from the butter trade in the city went to the commissioners with the purpose to deepen, widen and improve the harbour and river of Cork. When the first Cork Harbour Commissioners (CHC) board was appointed in 1813 the membership resembled that of the protestant-controlled corporation structure; brewing, butter, shipping, butter, sugar, and timber interests reflected the commercial interests of the board members. In 1814, the infamous ‘Cocket and Entry Tax’ Act or ‘The Commercial Buildings Act’ ‘was imposed as another form of revenue and was regarded as simply a tax on trade.[6] The tax was peculiar to Cork and was a tax on customs documents rather than the value or quality of goods.

A first step to improve the port’s infrastructure was the passing of the Butter Weighhouse Act (1813) under which commissioners were appointed to improve the ‘harbour and river of Cork’.[5] Significantly, twenty-one merchants of the city were appointed as commissioners. One third of the fees received by the Weighmaster from the butter trade in the city went to the commissioners with the purpose to deepen, widen and improve the harbour and river of Cork. When the first Cork Harbour Commissioners (CHC) board was appointed in 1813 the membership resembled that of the protestant-controlled corporation structure; brewing, butter, shipping, butter, sugar, and timber interests reflected the commercial interests of the board members. In 1814, the infamous ‘Cocket and Entry Tax’ Act or ‘The Commercial Buildings Act’ ‘was imposed as another form of revenue and was regarded as simply a tax on trade.[6] The tax was peculiar to Cork and was a tax on customs documents rather than the value or quality of goods.

The inadequacies of the 1813 and 1814 Acts led to the passing of the Cork Harbour Act (1820) which constituted the Cork Harbour Commissioners (CHC) as a port authority. However, without capital funding forthcoming from the Government and the direction that maintenance should be financed from the port’s resources, it was not the most auspicious of starts for the new harbour authority. Under the Act, the total number of members of the board was thirty five, of which twenty-five members represented the city’s mercantile community.[7] Whilst there were several acts relating to the structure of the board it was the 1820 Act that was the primary legislation and remained in operation till the Harbours Act (1946) which endowed the commissioners with full responsibility for all the port’s receipts and payments.

Infrastructural Developments of Cork Port and Harbour in the Nineteenth Century

In 1815 the Harbour Authority requested the Civil Engineer Alexander Nimmo to conduct a study of the port. Nimmo was very critical of the condition of the quays, which he referred to as “… mostly imperfect masses of rubble stone …” Nimmo’s report identified main structural issues and possible solutions to improve the ports.[8] However, the cost of the works was seen to be prohibitive. It was clear to the board that dredging had to be the way forward. F O’C. Saunders, as a former harbour engineer, maintained that if funding had been provided for Nimmo’s proposals the port’s infrastructure would have been built sooner. [9] However, it must be noted that in such a scenario increases in port charges would not have been acceptable to the board of CHC.

Investment in dredging equipment was to be the initial priority of CHC. By 1828, 23,000 tons had been raised and by 1832, 182,877 tons had been dredged. Dredgers were bought in 1839 and 1851 to accelerate the deepening of the riverbed. Between 1857 and 1864, a total length of 18,580 feet of quays was piled. Dredging produced a channel 11 feet deep from Horse Head (near Passage) in the lower harbour to Cork city. By 1884 the city quays, North Deepwater Quay (NDWQ) had a length of 1,400 feet with 20 feet l.w.o.s.t (low water at spring tides) and the South Deepwater Quay (SDWQ) had 600 feet in length and 23 feet l.w.o.s.t. (low water at spring tides). The dredging programme was seen as a success in the development of Cork Port particularly as 1,277,502 tons were dredged, in the 10 years ended 1849.

The Shadow of the Famine and Emigration

In Ireland by 1846 more than half of the potato crop was unusable and widespread hardship was felt among the rural and urban poor. In respect of the port, the commissioners were tasked with overseeing the importation of Indian corn which was to be shipped from the United States and Cork became the reserve depot for the whole country. Reflecting the inadequacies of Cork and its port, the ships that arrived could only discharge part of their cargo in the lower harbour at Haulbowline and had to be further lightened at Passage before proceeding to Cork.[10] In 1846 CHC had agreed that the American relief food vessels arriving in Cork would have their dues remitted. Between 1845 and 1851 over 70,000 emigrated from Cork city. The Famine period was nevertheless significant in terms of the volume of shipping in the port and generating finances for the authority; with tonnage and imports, during the fifty years ended 1849, at their highest in 1847 and 1849.

The Port of Cork – A Financial Perspective 1830-1900

Quay expenditure along with dredging costs consistently amounted to over 60 per cent of total expenditure during the nineteenth century period. This expenditure mostly related to the upper river. The second quarter of the nineteenth century was an important phase of development and investment for the port. Many of the quays built remain in situ and constitute a defining feature of the port’s history and character.

The total assets of Cork Harbour Commissioners were valued at £32,000 in 1868, by 1900 this was valued at £337,000 and comprised mainly Estate (£205,000) and Investments (£66,000) assets. Shipbuilding was an important industry to Cork Port but had declined from the 1860s due to the demise of the port’s transatlantic business which led eventually to transshipments through the larger English ports. As a result, the industry was deprived of lucrative contracts. [11]

From 1870 shipping was now able to come up the river without the aid of lighters making imports more price competitive and were seen to grow over the century, unlike exports. It could be argued that the evidence of imports increasing could be an indication that consumption was rising from increased living standards in the port and its agricultural hinterland and was more important than the exports generated by agricultural and industrial production. Illustrating this view, imports between 1870 and 1901 increased by 40 per cent with exports remaining static. With a combination of borrowing and increased income from imports, the state of the harbour improved significantly for shipping coming up into the city. The period between 1860 and the end of the nineteenth century stands out as the critical period in the development of the city quays and the channel up from the lower harbour and in particular, Passage. The following table illustrates the importance of imports to the port during the nineteenth century.

Table 1: CHC Imports, Exports, Tonnage Income as % of Total Income 1830-1900

| Year | Imports | Exports | Tonnage | Harbour | Total | Overall |

| Income | ||||||

| £ | £ | £ | £ | £ | % | |

| 1830 | 2038 | 2000 | 1660 | 5698 | 93 | |

| 1840 | 2456 | 2018 | 2572 | 179 | 7225 | 98 |

| 1849 | 5036 | 1843 | 2804 | 1166 | 10849 | 79 |

| 1861 | 9047 | 2984 | 5356 | 2362 | 19749 | 98 |

| 1870 | 10887 | 4156 | 6785 | 2681 | 24509 | 99 |

| 1880 | 12760 | 5212 | 9237 | 4153 | 31362 | 86 |

| 1890 | 12837 | 4213 | 15972 | 2670 | 35692 | 99 |

| 1900 | 15723 | 4107 | 15758 | 2434 | 38022 | 98 |

Source: Cork and County Archives (CCCA), Cork Harbour Commissioners Collection (PC), the detail was adapted from the annual accounts of Cork Harbour Commissioners, 1830-1900.

Cork Harbour Commissioners – Mercantile members

A significant shift took place in the religious makeup of the mercantile members of the board during the 1870-1900 period as is illustrated in the following table.

Table 2: CHC Mercantile Members 1870-1900.

| Mercantile Members | |||

| Year | Catholic | Protestant | |

| 1870 | 43% | 57% | |

| 1900 | 56% | 44% | |

Source: O’Riordan, Patrick, Portraiture of Cork Harbour Commissioners (Cork, 2015).

This slow shift reveals the growing power and influence of the Catholic middle classes in running the harbour, but the Protestant influence was still strong at the end of the nineteenth century, reflecting its significant over representation within the Cork city establishment. Within the port, the Protestant ownership of a significant share of the steamship companies at this stage had a strong influence on the composition of the board. A patriarchal structure was very much to the fore in the operation of the board particularly where operations and staffing were concerned, and nepotism was part and parcel of managing the authority.

Cork: The Lower Harbour

In the second half of the nineteenth century, the port of Cork began to handle increasing quantities of mail and it became the most important port of departure for transatlantic emigrants. This was due primarily to the arrival of the transatlantic steamship companies, which began to call to Ireland in 1859. The economy of the lower harbour, in particular Queenstown, benefitted from the American mails and the significant emigration numbers from Cork. Yet lower harbour infrastructure investment, in the nineteenth century, was not seen as cost-effective by CHC, particularly as activity in the upper harbour was financing investment in the lower harbour.[12] This led to increased tension between upper and lower harbour interests.

An integral part of the lower harbour was Haulbowline which had been a base for the British navy through the centuries. It must also be remembered that the British Admiralty and Treasury were the ports biggest customers, particularly, up to the late 1780s. The importance of the presence of the British army and navy cannot be under-estimated particularly in the awarding of lucrative contracts locally such as textiles for uniforms and gunpowder. In terms of the Royal Navy, Cork harbour never became a base for major units however they did call for fuel and provisions.

Conclusion

Like many organisations, it seems that CHC responded quite slowly to the immediate challenges it faced after it was established. It took some years to develop the harbour into a safe, cost effective and coherent operation adequately handling the import and export demands of the port. Improvements took place over decades rather than years, but once the necessary infrastructure was put in place the benefits were immediate. Given that the region failed to industrialise, and the population of the city stagnated in the second half of the nineteenth century, and the population of its hinterland declined, the port performed reasonably well relative to its competition in the Munster region, Limerick and Waterford. Dublin and Belfast in contrast both had demographic advantages and greater industrial development and were in a better position to handle the expansion of Anglo-Irish trade in the nineteenth century.

Notes

[1] Patrick Flanagan, “The Cork Region: Cork and County Cork, c.1600-c.1900,” (eds.) B. Brunt and K. Hourihan, Perspectives on Cork Special Publication No. 10 (Dublin: Geographical Society of Ireland, 1998,) 3.

[2]See John Joseph Keane, “Four Tales of a City. The Transformation in the Social, Economic and Political Geography of Cork City, 1780-1846,” unpublished MA thesis (Cork: University College Cork, 1990).

[3] William O’Sullivan, The Economic History of Cork City from the Earliest Times to the Act of Union (Cork: Cork University Press, 1937), 148.

[4] Patrick J McCarthy, “An Economic History of the Port of Cork: 1813-1900,” unpublished M. EconSc. thesis (Cork: University College Cork, 1949), 12-13.

[5] The Butter Weighhouse Act of 1813. (53. Geo, 111.c.70).

[6] For a full history of this tax see Mary Lantry, “The Cocket Tax in Cork: A Tax in the Context of its Time and Place,” unpublished MA thesis (Cork: University College Cork, 2018). The tax was abolished under Statutory Instrument No. 274/1947 – Harbours Act, 1946.

[7] Cork Harbour Act 1820. (1. Geo.iv.c.52); Patrick O’Riordan, Portraiture of Cork Harbour Commissioners (Cork, 2015), 288.

[8] Alexander Nimmo, Report to the Harbour Commissioners on the Means of Improving the River and Harbour of Cork (Cork, 1815). Nimmo had a major influence in the emergence of the Irish Ordnance Survey, the Office of Public Works, the Hydrographic Survey of Ireland and the Fisheries Commission.

[9] F. O’C Saunders, ‘The Development of the River Port of Cork City’, The Institution of Civil Engineers of Ireland, vol. 82, (March 1956), 115. Saunders was harbour engineer from 1933 to 1960.

10 Daire Brunicardi, Haulbowline: The Naval Base and Ships of Cork Harbour (Dublin: The History Press Ireland, 2002), 40.

[11] Andy Bielenberg, Cork’s Industrial Revolution: 1780-1880 (Cork: Cork University Press, 1991), 113 and 122.

[12] Sean Pettit, History of the Port of Cork (unpublished, Cork Harbour Commissioners, 1996), 328. The original manuscript is kept by the Port of Cork Company. The Port of Cork Company succeeded Cork Harbour Commissioners in 1997. Pettit refers to a submission made by Sir James Long to the Ports and Harbours Tribunal 1930 where he pointed out that the lower harbour was being subsidised by the upper harbour. Long was the General Manager of the port.

Tom, I found your article very interesting and well researched.