The Sailor’s Hornpipe, also known as “The Jig of the Ship,” “Jack the Lad,” or “Deck Dancing,”[1] was a common sight in ports, danced and performed in sailortown areas across the globe. The Sailor’s Hornpipe became a staple dance of the Royal Navy, so much so “the sailor’s hornpipe was one of the glories of the English Navy.”[2] The hornpipe developed into a highly recognisable cultural representation of British Tars on stage, rising in popularity from the eighteenth century, and the music of which became widely recognised when it was adapted for the cartoon Popeye the Sailor Man in the 1930s.

The Sailor’s Hornpipe, also known as “The Jig of the Ship,” “Jack the Lad,” or “Deck Dancing,”[1] was a common sight in ports, danced and performed in sailortown areas across the globe. The Sailor’s Hornpipe became a staple dance of the Royal Navy, so much so “the sailor’s hornpipe was one of the glories of the English Navy.”[2] The hornpipe developed into a highly recognisable cultural representation of British Tars on stage, rising in popularity from the eighteenth century, and the music of which became widely recognised when it was adapted for the cartoon Popeye the Sailor Man in the 1930s.

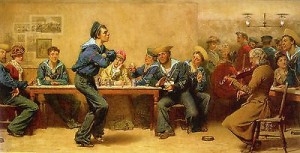

The Sailor’s Hornpipe is a traditional seafaring dance accompanied by music and it is a significant form of dance as it replicates and performs various ship-based sailor tasks like, climbing, rigging and hauling, that a sailor would complete as part of their on-board daily duties. (See clip for sailors from the Britannia Royal Naval College dancing the Hornpipe). The hornpipe was thus an easy dance to do in groups, or alone, and in small spaces, with the tempo suited to the beat of on-board life and often danced on ships as a way for sailors to maintain physical fitness.[3] On shore, sailors performed the hornpipe as a way to entertain themselves, often undertaken as part of the revelry of a ‘run ashore’, after a few drinks, to attract the attention of women, or for mere bravado.[4] Thus, alongside sailors’ distinctive dress, language and body adornments of tattoos, the hornpipe became another recognisable cultural symbol of Jack being in port and none more so than when on the stage.

The Sailor’s Hornpipe is a traditional seafaring dance accompanied by music and it is a significant form of dance as it replicates and performs various ship-based sailor tasks like, climbing, rigging and hauling, that a sailor would complete as part of their on-board daily duties. (See clip for sailors from the Britannia Royal Naval College dancing the Hornpipe). The hornpipe was thus an easy dance to do in groups, or alone, and in small spaces, with the tempo suited to the beat of on-board life and often danced on ships as a way for sailors to maintain physical fitness.[3] On shore, sailors performed the hornpipe as a way to entertain themselves, often undertaken as part of the revelry of a ‘run ashore’, after a few drinks, to attract the attention of women, or for mere bravado.[4] Thus, alongside sailors’ distinctive dress, language and body adornments of tattoos, the hornpipe became another recognisable cultural symbol of Jack being in port and none more so than when on the stage.

Sea dances were a prominent feature in stage productions from the sixteenth century, yet it was during the nineteenth century that the Sailor’s Hornpipe became more ingrained in popular musical and theatre culture.[5] T.P. Cooke, who specialised in nautical roles on stage, made the dance infamous, propelling the hornpipe into Victorian theatres and music halls.[6] In part, Cooke’s success with the hornpipe was that he “manages to represent a tar to a nicety,”[7] with the London Literary Gazette stating “he is an inimitable seaman, dances a hornpipe to perfections, swears sailors’ oaths unprofanely and twitches up his expressible with an air very amusing to land-lubbers.”[8] Another reason for Cooke’s hornpipe success is due to the claim that he visited every port in England, assimilating all the hornpipe variations found there.[9] Whether he did or not, there is evidence of hornpipes taking on a port-regional identity. Various steps of the hornpipe were adapted to give it a regional and local flavour, and subsequently these hornpipe variations took on the names of the ports in which they were adapted, such as the “Derry Hornpipe,” “Belfast Hornpipe,” “London Hornpipe,” and “Portsmouth Hornpipe.”[10]

What this brief exploration of the Sailor’s Hornpipe begins to suggest is that, much like other sailor-influenced cultural practices such as tattooing, dance was also replicated and adapted along the waterfronts of the world, merging practices and cultural symbols of the sea, ship, shore and stage. Through the medium of dance, sailors and port communities alike could express their occupational, regional and local identity, creating a form of socio-cultural intercourse between sea and shore. Moreover, not only was the hornpipe adapted to suit local port communities and to entertain crowds on the stage, it also offered sailors a way to express themselves when in port, and show that, after all “a sailor who could not dance a hornpipe was no sailor at all.”[11]

What this brief exploration of the Sailor’s Hornpipe begins to suggest is that, much like other sailor-influenced cultural practices such as tattooing, dance was also replicated and adapted along the waterfronts of the world, merging practices and cultural symbols of the sea, ship, shore and stage. Through the medium of dance, sailors and port communities alike could express their occupational, regional and local identity, creating a form of socio-cultural intercourse between sea and shore. Moreover, not only was the hornpipe adapted to suit local port communities and to entertain crowds on the stage, it also offered sailors a way to express themselves when in port, and show that, after all “a sailor who could not dance a hornpipe was no sailor at all.”[11]

Notes

[1] For history of name variations, see Martin Robson, Not Enough Room to Swing a Cat: Naval Slang and its Everyday Usage, (London: Conway, 2008), 166 – 167. For deck dancing, see Front Cover of, The Graphic, 29th July 1905.

[2] The Countess of Blessington ed., The Keepsake, (London: D Bogue, 1843), 194.

[3] It is said that Captain Cook regularly made his crews dance the hornpipe to stay active, see, Robson, Not Enough Room to Swing a Cat, 167.

[4] Steward Ellis, George Meredith: His Life and Friends in Relation to His Work, (London: Grant Richards, 1920), see letter conveyed in this book by S.B. Ellis, 27 and Dan Worrall, The Anglo-German Concertina: A Social History, Volume 1, (Fulshear: Concertina Press, 2009), 311.

[5] Terence Freeman, Dramatic Representation of British Soldiers and Sailors on the London Stage, 1660 – 1880, (London: E, Mellen Press, 1996), 127 – 128.

[6] Michael Pisani, Music for he Melodramatic Theatre in Nineteenth Century London and New York, (Iowa: University of Iowa Press, 2014), 99 and Tamara Stevens and Erin Stevens, Swing Dancing, (New York: ABC-Clio, 2011), 8

[7] Figaro in London, Vol. 1, (London: W. Strange, 1831), 100.

[8] The London Literary Gazette and Journal of Belles Letters, Arts and Sciences, (London, 1830), 692.

[9] Ivor Forbes Guest, “The Empire Ballet,” Society for Theatre Research, (1962), 83.

[10] Fiona Ritchie, Doug Orr, Darcy Orr, “The Dance at Sea,” Wayfaring Strangers: Musical Voyage from Scotland and Ulster to Appalachia, (Chapel Hill: UNC Press Books, 2014). See also, Arthur Franks, Social Dance: A Short History, (London: Routledge & K. Paul, 1963), 83 and See also, Allan Arnold, “To Pass the Time Away: Voyagers’ Attitudes toward Music,” in Patricia Carlson, ed., Literature and Lore of The Sea, (Amsterdam, Rodopi, 1986,) 51 -58; 54.

[11] Blessington, The Keepsake, 194.

A very interesting article!

I am interested in the type of dance performed on board ship. I have been viewing a clip of stoker Edward Mackenzie dancing on the Terra Nova during Scott’s antarctic expedition from Herbert Ponting’s The Great White Silence. He is not dancing a ‘Sailor’s Hornpipe’ but step-dancing in the heel and toe style common in East Anglia and the southern counties. Mackenzie was born in Norfolk but his mother was born in Fareham. The family lived for a period of his childhood in Portsmouth. I am intrigued to know where he learnt his stepping – ashore or on board. I would also like to know whether the dancing on ship was generally heel and toe stepping or whether the sailors did actually dance the ‘Sailor’s Hornpipe.’

It would be good to know if there are any other film clips or written descrpitions of the dancing.

Thanks.