The opening of the Jutland exhibition coincides with the one hundredth anniversary of the Battle of Jutland, which was fought from 31 May to 1 June 1916, and has been commemorated locally and at a wider level.[1] The focus of the exhibition is upon an intense moment of British naval history; 36 hours of warfare which is described by the exhibition as “the battle that won the war”.[2] The layout and displays are engaging and immerse visitors within the sights and sounds of the battle through reconstructed films, objects recovered from the battle such as flags and signalling equipment, and personal artefacts of those who fought at Jutland including letters and diaries.

The opening of the Jutland exhibition coincides with the one hundredth anniversary of the Battle of Jutland, which was fought from 31 May to 1 June 1916, and has been commemorated locally and at a wider level.[1] The focus of the exhibition is upon an intense moment of British naval history; 36 hours of warfare which is described by the exhibition as “the battle that won the war”.[2] The layout and displays are engaging and immerse visitors within the sights and sounds of the battle through reconstructed films, objects recovered from the battle such as flags and signalling equipment, and personal artefacts of those who fought at Jutland including letters and diaries.

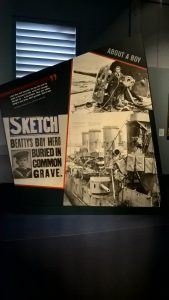

I conducted thirty interviews with visitors to the exhibition over the course of two days. This research forms part of a larger national project run by Dr Jessica Moody (University of Portsmouth) and Dr Geoff Cubitt (University of York) which considers the attitudes of museum visitors to the First World War and the current centenary. The aspect I found most striking from the narratives was the interviewees’ sense of collective identity and connection with the lived experiences of those involved in the battle. A sense of inclusivity and British citizenship were prominent features of the interviews, whereby interviewees situated Jutland and the First World War’s role as part of ‘our’ heritage and its relevance within British history. This draws parallels to the work of Linda Colley and Michael Paris exploring the implications of war and Britain’s national identity; notably Colley argues that we are a nation “forged” by war.[3] Beyond grand narratives of battles and notions of collective identity, what was also apparent from the interviewees was the futility of the First World War.[4] This is comparable to Kenneth O. Morgan’s summary of Jutland, whereby he referred to it as “at best a draw between the British and German high fleets”.[5] Some of the interviewees highlighted in particular Jack Cornwell as a poignant and tragic example to represent the loss of human life, a boy of sixteen who died at the Battle of Jutland. He featured in a display panel and a sketch of him can be seen for the first time on public display. Interviewee sympathy was not only limited to location; the situation and suffering of both Britons and Germans was noted within the interview conversations from visitors of varied nationalities including Britons, Germans, Australians, Americans and Swiss.

The exhibition was particularly emotive for some of those who had relatives who were part of the  Battle of Jutland. One interviewee reflecting upon her Great Uncle’s service on-board HMS Malaya said she was “very proud and humbled”, and described being at the exhibition as “quite emotional”, especially regarding the supposed “terrible impact” the battle had upon him.[6] Another interviewee’s Grandfather was the chief stoker on-board HMS Queen Mary, she felt “touched” and “grateful” that he survived the Battle of Jutland, saying the exhibition “brings it home…what they went through”.[7] Their narratives displayed interplay between pride for their relatives’ role in the battle but also sadness for the conditions their relatives endured and for those who died. Such processes involved within memory recollection have been analysed extensively by oral historians, in particular the interaction between public and private memories.[8] The interviews I conducted at the Jutland exhibition serve as a reminder that memories draw connections between the past and present, and identities are multiple, complex and shifting. Whilst individuals drew upon public discourses espousing paralleled sentiments of nationhood and pride, idiosyncratic narratives were also evident and conveyed with emotive clarity, revealing personal connections with the past and the significance of family stories.

Battle of Jutland. One interviewee reflecting upon her Great Uncle’s service on-board HMS Malaya said she was “very proud and humbled”, and described being at the exhibition as “quite emotional”, especially regarding the supposed “terrible impact” the battle had upon him.[6] Another interviewee’s Grandfather was the chief stoker on-board HMS Queen Mary, she felt “touched” and “grateful” that he survived the Battle of Jutland, saying the exhibition “brings it home…what they went through”.[7] Their narratives displayed interplay between pride for their relatives’ role in the battle but also sadness for the conditions their relatives endured and for those who died. Such processes involved within memory recollection have been analysed extensively by oral historians, in particular the interaction between public and private memories.[8] The interviews I conducted at the Jutland exhibition serve as a reminder that memories draw connections between the past and present, and identities are multiple, complex and shifting. Whilst individuals drew upon public discourses espousing paralleled sentiments of nationhood and pride, idiosyncratic narratives were also evident and conveyed with emotive clarity, revealing personal connections with the past and the significance of family stories.

The Jutland Exhibition at Portsmouth Historic Dockyard from the National Museum of the Royal Navy will be open until spring 2019; there is also an interactive experience via their website: www.jutland.org.uk where it is possible to share stories of people who fought at Jutland.[9] Twitter updates are viewable for Portsmouth Historic Dockyard at: @PHDockyard and for the National Museum of the Royal Navy: @NatMuseumRN

References

[1] Local newspapers in Portsmouth, the Isle of Wight, Kent, Dorset, Plymouth, South Wales, Hull, Edinburgh, Liverpool and Belfast: http://www.portsmouth.co.uk/news/defence/world-remembers-sacrifices-made-at-battle-of-jutland-100-years-on-1-7407708; http://www.portsmouth.co.uk/news/defence/jutland-commemoration-service-in-pictures-1-7410041; http://www.iwcp.co.uk/news/news/events-to-mark-isle-of-wight-sacrifices-during-battle-of-jutland-95058.aspx; http://www.kentonline.co.uk/medway/news/medway-commemorates-the-battle-of-96724/;http://www.dorsetecho.co.uk/news/features/lookingback/14481671.LOOKING_BACK__100th_anniversary_looming_of_loss_of_Weymouth_lives_in_First_World_War_battle/; http://www.plymouthherald.co.uk/crowds-gather-plymouth-hoe-mark-100th-anniversary/story-29341535-detail/story.html; http://www.westerntelegraph.co.uk/news/14518724.THE_LONG_VIEW__The_Gwent_sailors_who_fought_and_died_at_Jutland/; http://www.hulldailymail.co.uk/battle-jutland-100th-anniversary-bravery/story-29337839-detail/story.html; http://www.edinburghnews.scotsman.com/news/hundreds-mark-centenary-of-wwi-s-battle-of-jutland-1-4140587; http://www.liverpoolecho.co.uk/news/liverpool-news/liverpool-sailor-among-those-honoured-11409019; http://www.belfasttelegraph.co.uk/news/northern-ireland/jutland-survivor-hms-caroline-centre-stage-for-centenary-34760141.html; National newspapers: https://www.theguardian.com/world/2016/may/31/battle-of-jutland-centenary-marked-with-service-in-orkney-islands; http://www.independent.co.uk/news/uk/home-news/jutland-battle-of-jutland-centenary-100th-anniversary-ww1-1916-navy-germany-britain-who-won-what-a7057336.html; German newspapers: http://www.spiegel.de/einestages/skagerrak-schlacht-groesste-seeschlacht-der-geschichte-a-1094260.html; http://www.faz.net/aktuell/gesellschaft/skagerrak-schlacht-vor-100-jahren-im-ersten-weltkrieg-14254086.html; http://www.faz.net/aktuell/skagerrak-die-groesste-seeschlacht-des-ersten-weltkriegs-14260154.html; For a list of First World War centenary events see: http://www.britishlegion.org.uk/remembrance/ww1-centenary/jutland-100/?gclid=CJj9wKHqrs0CFcG6Gwodw6INOQ; all accessed 17/06/16.

[3] Linda Colley, Britons Forging the Nation, 1707-1837, (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2009); Michael Paris, Warrior Nation: Images of War in British Popular Culture, 1850-2000, (London, Reaktion, 2000).

[4] The issue of the futility of war is part of a broader ‘discourse’ of the First World War, see Ross Wilson, “Still fighting in the trenches: ‘War discourse’ and the memory of the First World War in Britain” Memory Studies 8, no 4 (2015): 454-469; Dan Todman has also analysed the tropes of the First World War: Dan Todman, The Great War: Myth and Memory (London: Hambledon, 2005).

[5] Kenneth O. Morgan, Twentieth Century Britain: A Very Short Introduction, (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2000), 5.

[6] Interview PD25, 14 June 2016.

[7] Interview PD19, 14 June 2016.

[8] Lynn Abrams, Oral History Theory, (London: Routledge, 2010), 7; Mary Fulbrook, “History-writing and ‘collective memory”, in Writing the History of Memory ed. Stefan Berger, and Bill Niven, (London: Bloomsbury, 2014), 84; Anna Green, “Can memory be collective?”, in The Oxford Handbook of Oral History ed. Donald A. Ritchie, (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2011), 96; Alessandro Portelli, “What makes oral history different”, in The Oral History Reader ed. Robert Perks, and Alistair Thomson, (London: Routledge, 2016); 52-53; Alistair Thomson, “Anzac Memories putting popular memory theory into practice in Australia”, in The Oral History Reader ed. Robert Perks, and Alistair Thomson, (London: Routledge, 2016), 343-353.

[9] This website was based on research conducted by various ongoing project teams who contributed their data to the NMRNP. Dr Mel Bassett and Professor Brad Beaven from the Port Towns and Urban Cultures group at the University of Portsmouth, whose research is funded with support from the AHRC Gateways to the First World War Centre; The U3A, with financial support from the AHRC Gateways to the First World War Centre and by the HLF for their project on the impact of the Battle of Jutland on Portsmouth and Gosport; Other project partners included the University of the Third Age, the Royal Hospital School and Nick Jellicoe’s Jutland1916.com project.

Comments are closed.