In my last post, I discussed why sea blindness is not the most useful way to characterize twenty-first century sensibilities. Let’s face it, it just doesn’t make much sense at a time when beachgoers have to be warned, “Don’t take selfies with seals.” Instead, I argued, we should think critically about sea visibility, which is proliferating in many new media formats. In that post, I discussed examples like Jacques Cousteau’s films, and the sorts of projects that Cousteau might undertake if he had access to today’s technology.

I focused on the ocean optimism movement precisely because it has focused its energy on shifting the terms of how sea visibility works. Which messages are getting a widespread viewing? Why those messages? The founders of ocean optimism argued that a barrage of bad environmental news, in the absence of contrary examples or plausible reasons for hope, bred fatalism or apathy, which we can ill afford right now.

However, much of the discussion about ocean optimism that I’ve seen so far seems focused on replacing one set of headlines with another. Science communication (which has its own very active hashtag, #scicomm) has to be part of the solution, but a recent article in the Washington Post suggests a different way to conceive of the problem as a whole.[1]

Many people are well-informed on climate change, but taking little action about it. What distinguished those who did take action? Simply put, “If a person knows that friends and neighbors are participating, they may be more likely to do so as well.”

The focus here is not so much on what headlines people are reading, but what they are seeing in their own community and social circle. “Highlighting positive experiences from similar people” and “demonstrating ways in which individual or collective efforts helped achieve concrete goals” foster a belief in one’s own efficacy, creating a snowballing effect where “climate action may be infectious.”[2]

The Post quoted Kathryn Doherty, the author of the study, as stressing the need to “target your audience and figure out what motivates them… [and] then come up with messages or experiences designed for that particular segment of the population.”

What interests me about the article, though, is it suggests not so much that we need better curators and coaches (who astutely “target” audiences) to help us think about environmental issues, but that we ourselves are the curators, coaches, and role models for people in our community and our social circle.

Social media is, increasingly, the place where we look to see what peers, family, friends, and neighbors are doing. It is also, notoriously, the home of many micro-groups and echo chambers, but as Doherty notes, we can probably only motivate the population one segment at a time.

The lesson of books like Microtrends and The Long Tail here would be that sports enthusiasts and self-described adventurers will engage with the environment in one way; contemplatives, seekers, and nostalgics in another; and so on down the line. Each subgroup would love to “put themselves in the picture,” but each will have its own quite different sense of what that means.

In that spirit, I have turned to Twitter for some insight as to how we are actually engaging with the ocean today. Here is a little mosaic of what I found there.

The White Crests Turned Pink

White crests of waves turned pink with #plasticbottles yesterday. #marinedebris @Seasaver @mcsuk pic.twitter.com/KPOEigQodR

— Newquay Beachcombing (@Newquaybeach) January 5, 2016

In January of this year, Twitter users in Cornwall reported that “White crests of waves turned pink with #plasticbottles yesterday.” The fact that the waves, even from a distance, had changed to such an unnatural color does underscore not just the pollution, but the scale and severity of it.

Since the first plastic objects were reported in the 1970s, scientists had to devise a name for the phenomenon. They settled on “marine debris.” Ecotourists and surfers raged against the floating plastic bag, which is banned or deterred in a number of countries today. Despite these efforts, plastic marine debris spread across the planet, even the Arctic Ocean.

From a certain perspective, Cornwall’s pink tide shouldn’t surprise anyone, and scarcely qualified as news. If you’ve already heard about plastic marine debris in the remotest locations, its appearance near the English Channel is hardly a game-changer. Even bizarre mass inundations of unlikely objects are now regular occurrences. Mishaps with container ships have led to surges of Hewlett Packard printer cartridges, cigarette packs, and the stray tidbits of a shipment of Legos. Recently, the sighting of a lifesize floating plastic skeleton resulted in the mobilization of a coastguard rescue team.

Put another way, why should tweets from Cornish beaches have a special impact when people could just as easily follow the story as summarized by the Guardian, or on the BBC? If there are people with the skills and funding to assemble this Hollywood-style movie trailer promoting a new documentary about marine debris, shouldn’t we leave consciousness-raising to the experts?

Capturing an outrage on the Cornish coast with a smart phone snapshot is an affirmation of what we might call the neighborly coast or the everyday coast. Too often, something like the Great Barrier Reef stands in for the oceans, as we see in a lot of mainstream journalism. If the local coast is overlooked, that is replete with political dangers. When “paradise” is destroyed, do we assume there’s nothing left to save? Do we become complacent because surely no one will allow “paradise” to be compromised, so we tune out the seemingly banal local environmental issues?

We shouldn’t forget to ask how the photographers themselves were changed by the experience of taking these pictures and sharing them. Anyone with a smart phone can become a citizen journalist or a citizen activist now. It doesn’t take a lot of planning, and you don’t need anyone’s permission. We’ve seen a lot of evidence in recent years that DIY (do it yourself) politics, crowdfunding, and crowdsourcing are powerful in part because these are activities that engage people and build communities of shared values and interests in a way that older forms of media (and politics) generally didn’t.

Coming back to the consumer’s experience, though, in an era of cynicism about most institutions—including the media—a grainy photograph snapped in the heat of the moment commands attention in a distinctive way. There is also a special effect with repetitive photographs on social media (linked, perhaps by a hashtag) that a one-off news item doesn’t achieve. Those of us familiar with Twitter have experienced the force of accumulating messages, updates, and interactions with messages on a single theme.

Then there is the immediacy of the image; you can see the pink tide crest, almost in real time. I’m not disputing that the conventional media eventually deliver the “same” information. However, social media invites us to look over someone’s shoulder in a way that most journalism, and most science, doesn’t.

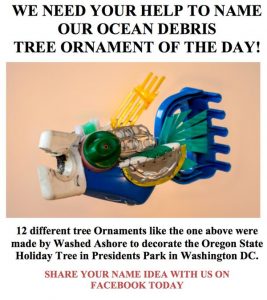

Tweet from Dec 17, 2015, 5:26:10 PM; image credit: @oceanwire, @washedashoreart

A Christmas tree ornament made from marine debris

I find this tweet interesting for many reasons. Even if we are in an era where people “read with their thumbs” as they flick through a timeline, a naming contest for this fanciful composite fish could make them slow down and engage at some level—or even share the image with friends.

The fish’s destination—here tactfully called a “Holiday Tree”—is also significant. Although multiculturalism has brought an increasing recognition of different holidays, the lighting of the national Christmas tree remains a traditional civic role of the U.S. President. In 2015, the national Christmas trees of both the United States and of Canada featured marine debris ornaments like the one pictured in this tweet.

The decision to reshape the debris into something new was itself an interesting tactic. Assembling a bunch of plastic tidbits that never belonged in the ocean into a faux fish sporting eye-popping tropical colors is cute, but it’s also a sharp comment. Perhaps that’s in synch with the spirit of our age, when many people get their news from The Daily Show, and Saturday Night Live skits about Presidential candidates can themselves make headlines.

Does that mean that environmentalists should dial back on the use of disturbing photographs that also circulate on social media, like those of sea turtles wedged inside plastic lawn chairs or with plastic straws up their nostrils? Not necessarily. But “name this plastic imaginary fish” is going to capture a different demographic.

In my social media searching, I found an unending thread of #beachclean day projects, and also of whimsical amateur collages made with what was gathered. The Christmas ornament was done by professionals (their Twitter account is @WashedAshoreArt), but there seems to be a common impulse to arrange the #marinedebris oddities into patterns and photograph them. Some people pose plastic soldiers in the sand and take mock-heroic snapshots. Sometimes there’s accompanying text with an edge to it—“in case you didn’t know, this is what we’re finding on the beach these days,” or even “… more plastic than sand here.”

What this amounts to is a distinct form of sea visibility. As with the case of the citizen journalists and their #plastictide tweets, maybe the impact on the creators is as important as how (or whether) the work finds an “audience.”

Tell us what this location means to you

Who remembers Mullion Harbour with the sloping breakwater? @NTSouthWest @HistoricEngland #mullion #coastalhistory pic.twitter.com/1K4d2b4gcE

— Lizard NT (@LizardNT) October 14, 2015

Lizard National Trust in Cornwall has a question for us: “Who remembers Mullion Harbour with the sloping breakwater?”

They paired that question with a black-and-white photograph. They also used a hashtag that I thought I understood, because I invented it. What is #coastalhistory doing here, though?

This tweet was a lesson to me about how our creations can amble off in their own independent ways. And when I saw how many public historians, local citizens, and museum curators turned up at the “Firths and Fjords” coastal history conference in Dornoch this Spring, I began to understand the pattern.

The Lizard National Trust used coastal history to invite the public to join a conversation, and invoke a sense of place and even of heritage. The tweet was a prompt: What declarations of meaning, relevance, or investment would result?

To get a better picture of the potential here, do a Twitter search for #coastalrevivalfund. I especially enjoy this one because it takes a broad view of “coast”: it’s not just about iconic lighthouses and cliffs, but also anthropogenic coasts like resort towns that have seen better days, beloved lidos, and so forth.

As an academic myself, I tend to have a pretty myopic perspective on the purpose and uses of a #coastalhistory hashtag, but its use as a tag for landscapes, seascapes, and coast walking photos suggests that it’s not just a subfield—coastal history could be an activity, or a way of seeing and experiencing. The happy wanderer can even use this tag to invite others to join in, or put themselves in the picture.

I think this may even have a role in mobilizing a different sort of constituency to address the current crisis. We’ve already seen some signs that one mainstream response to sea level rise will be a tactical withdrawal—patch up the damage, collect the insurance payouts, and carry on business as usual—perhaps a few hundred meters back from where the shoreline used to be. A chilling newspaper article offhandedly remarks that soon we will be able to 3D print entire cities in a hurry, allowing reconstruction of war-torn ruins but also, potentially, offering the mirage of a no-fault, easy-win solution to sea level rise.

Resisting this is going to require a stubborn attachment to place. Biophilia and sentimental ties to particular “charismatic” species have long been allies of environmentalism; in an era of rising seas, #coastalhistory tweets have the potential to align topophilia, the “love of place,” alongside them. The #coastalhistory tweet can be a place-making act of some significance. (And you don’t have to wait for a blue-ribbon government commission to decide that this location is worthy of a “heritage” designation.)

Our particular historical moment asks for more than this, however. There’s a certain intuitive force to “not in my backyard” (or “not on my beach”) environmentalism, but today’s situation also calls for thinking on the grandest scale. Is there evidence that people are rising to that challenge?

The Man Who Touched Two Continental Plates

In A Brief History of Time, Stephen Hawking remarked that there is no self-evident reason why a two-meter tall mammal, evolved to forage and do other routine mammal things, should be capable of thinking about the rate of the expansion of the universe, black holes, and so forth—much less arrive at the right answers about them.

What’s especially worrying right now is that as a species, it is suddenly necessary for the average two-meter denizen of this planet to be capable of reasoning quickly and accurately about things on a planetary scale, both at the macro- and micro- levels, and over a long time span. Understanding black holes is for extra credit; understanding climate change and other human impacts will be graded on a pass/fail basis.

I’ve mentioned some indignant and witty responses to “plastic tides.” There’s no guarantee, though, that your average seaside will show its damage in such an obvious way. Most of what we dump just sinks. Some scientists estimate that by the year 2025, there will be “nearly one ton of plastic for every three tons of fish in our oceans,” but the problem is actually hard to visualize: Most of that will degrade into tiny dangerous particles that can’t be sieved out or gathered up. They will, nevertheless, persist for thousands of years, contaminating the food chain.

Here’s another example that is even more alien to our everyday ways of experiencing the world. So far, the ocean depths have absorbed much of global warming, but that process can’t go on forever. Therefore, the average citizen needs to be mindful of a gradual process that they can’t see, running up the temperature in a dark, inhospitable place that even scientists rarely visit in person. This, for a species that has trouble thinking about “remote” and “long term” issues like fixing the roads, bridges, and municipal water systems that we use every day, or funding entitlement/retirement schemes for a graying population.

Of course (as with the roads, bridges, and entitlements examples) another obstacle to thinking big is that we might have to contemplate big sacrifices. Maybe it’s no surprise that (in my country, at least) some prominent politicians have openly ridiculed the idea of “stopping sea level rise.” Climate scientist Ken Caldeira recently spelled out where thinking on a planetary scale might lead, in painful detail:

“On a chilly morning, I heat my home and make myself some toast and coffee, and sink into my easy chair. I understand that in doing this I am contributing to killing off coral reefs and that I am affecting other marine ecosystems in unimagined ways. We know that protecting the oceans means we need, among other things, to stop using the atmosphere as a waste dump for our carbon dioxide pollution. We need to stop building things with smokestacks or tailpipes.”

These are challenges, not only to our powers of imagination, but to our political vision and moral courage that have to be unprecedented in the history of our species. As the physicist Michio Kaku recently quipped, the great and pressing cosmic question for us is now: “Is there intelligent life on Earth?”

Bear with me for a minute, but I think this very excited scuba diver might be a step in the right direction.

Today I touched North America and Europe… Under water. #scuba check out http://t.co/Z1NbimJmNh pic.twitter.com/oxvGPzz1Ds

— Chris Dunn (@ChrisDunnTV) April 25, 2014

“Today I touched North America and Europe… Under water.” This man has gone to Iceland, where it is possible to don scuba gear and bridge two continental plates with your fingertips. He’s happy to demonstrate.

I admit this photo doesn’t accomplish the whole leap to a planetary consciousness in one stroke. Some might ask “what was his carbon budget for travelling to Iceland?” But disparaging the oceanic selfie would be a mistake, I think.

First, Jill Neimark has reminded us of the power inherent in “real physical joy”. Planning to launch a joyless lifestyle trend, or political movement? Good luck with that.

But beyond this: for a two-meter tall land-dwelling mammal to touch two continental plates at once, and share that deed with the internet, is just the sort of visual labor that helps other people think big in their own ways.

Or is this just the latest installment of the anthropocentric hubris that got us into this mess? Lately I’ve been reading Oceanic New York, a collection of eco-criticism which contains a closely argued and provocative essay by Karl Steel about whether or not human beings are justified in asserting that we are superior to oysters.[3] He shows that there is a surprisingly long and distinguished Western intellectual tradition on this very question. The oyster caught the attention of many thinkers because it was an animal that had a startling resemblance to a vegetable growth or a dumb stone. Steel discusses examples from Pliny, Anglo-Saxon riddles, medieval bestiaries, and a famous 1646 letter by René Descartes on the nature of the soul. The Anglo-Saxons pitied it as a “footless” animal at the mercy of predators. Descartes scoffed at those who would attribute an immortal soul to animals, since that would have to include mere oysters and sponges. Unable to evade, improvise, or adjust, oysters occupied a very low place indeed on the Great Chain of Being.

There is a certain line of eco-criticism that seeks to de-center and dethrone humanity, and indeed to suggest that this is a necessary first step in getting out of our current predicament. Steel, writing in the context of Anthropocene climate change, remarks that it is high time we admitted that “we are more like oysters than not.” If the Earth’s temperature soars or the atmosphere takes a turn for the worse, our monkey-like agility won’t count for much. Steel suggests that maybe we should replace a human-centered view of the natural world with “oysteromorphism”: We, too, are “injurable” flesh clinging to a single rock, we’re not as clever and adaptable as we thought, and we are stuck, immobile, where it counts the most.[4]

I have some respect for this, but I would counter that it’s a lousy way to engage and motivate real human beings to positive action. For better and for worse, we are garrulous, manipulative, networking primates. We want to immerse. We want to touch, prod, and interact. We want to assign meaning. We want to be the hero of the drama. We want to connect with something larger than ourselves. And we want to take a selfie showing our friends that we did it!

Social media lends itself to this sort of “selfie politics.” This is helpful not just because social media is where a lot of people live now. Consider: what we can hold in our hand, apprehend on a beach walk, or capture with the camera on our phone is, of necessity, close to our physical size. It doesn’t overwhelm our conceptual grasp. Even if we can’t be there ourselves, we can picture it easily, and we can imagine ourselves doing or feeling the same things. This comes back to Doherty’s work on perceptions of efficacy; or if you like, ocean optimism in bite-sized pieces.

So far, what I’ve shown is a mosaic or collage of pieces that don’t touch at the edges. The tale of four tweets was of quite different types of individuals making meaning in divergent ways, rather in the spirit of Microtrends. However, what I’ve also noticed over the past six months is that these micro-engagements can grow, extend, and become more than the sum of their parts.

Beachcombers find an object that provokes them to start thinking about ocean current systems; recreational divers reinvent themselves as citizen scientists; and so on. It’s hard to express that in a snapshot, or in 140 characters. To appreciate this deeper and more sophisticated activity better, it’s helpful to shift the focus away from individual tweets, and over to blog posts and similar testimonials. I will consider those in the third and final part of this essay, later this summer.

Notes

[1] Thanks to Rebecca Altman (@rebecca_altman) for this citation, and for the Jill Neimark citation that I mention later.

[2] On this point, see also this piece: “Is Emotional Intelligence the Key to Tackling Climate Change?”

[3] Karl Steel, “Insensate Oysters and Our Nonconsensual Existence,” in Steve Mentz, ed., Oceanic New York, (Brooklyn: Punctum, 2015), 79-91. Thanks to Amy Cutler (@amycutler1985) for prodding me to read this book.

[4] Steel, “Insensate Oysters,” 85.

Comments are closed.