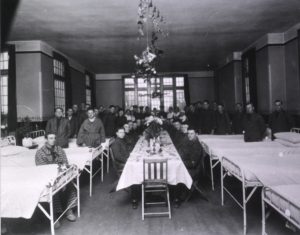

US Army Base Hospital No.33, Portsmouth, England: Ward (US National Library of Medicine. Copyright Free)

The First World War was unprecedented in the level of destruction and death that was inflicted across the world. Millions were killed or rendered into refugees and buildings, infrastructure, farmland and housing were left in a ruinous state by the impact of the conflict. However, whilst the war brought dislocation and disarray to the lives of many, it also transformed people and brought individuals together who would otherwise have never have met. As a port city, with movements of people and materials throughout the war, Portsmouth is a key site for understanding what was created during the conflict. As the centenary of the war is marked, it is useful to consider the ways in which new relationships were created amidst the trauma.

The arrival of servicemen and women from the United States in Portsmouth after the declaration of war against Germany by President Woodrow Wilson in April 1917 demonstrates this process. Portsmouth has long been a place where people from all over the world would meet but this process is expanded and accelerated by wartime conditions. This is especially the case for Americans in Portsmouth as wartime alliances between Britain and the United States ensured a warm welcome as officials put on a range of social events such as dances, concerts and teas. However, this was more than just a one-way process; American visitors brought ideas, practices and values to Portsmouth during the war.

The ‘Americanisation’ of Portsmouth had begun even before the major transportation of troops and medical staff from the United States to Europe. Indeed, the news of the entry of the United States into the war had sparked an outbreak of interest in all things American in the city. This can be seen with the celebration of Independence Day on July 4th 1917 outside the Guildhall.[1] Crowds of 10,000 people were recorded in some newspapers as attending the event which had been organised by Mayor Harold R. Pink.

The event was held in appreciation of the United States joining the war and a profusion of decorations covered the Guildhall. The two stone lions that adorn the building were brought into the celebration with one covered in the ‘Stars and Stripes’ whilst the other was draped with the Union flag. The celebration of an American national holiday to mark the overthrow of British rule was not regarded as incongruous in the light of wartime needs. Mayor Pink spoke glowingly of a new relationship that could emerge from the conflict.

“…this day is being celebrated in America as the birthday of the nation, and we, American’s cousin, wish them the very best wishes that can possible be sent them….We are quite delighted that our American cousins have joined with us, and we see in this an early conclusion of the war with a peace we trust will be lasting…”

With the reading of a telegram of thanks signed by Vice Admiral William S. Sims of the United States Navy sent by the Embassy in London and the chorus of ‘Three Cheers for America’ shouted by the crowd, the event heralded an interest in all things American in Portsmouth.

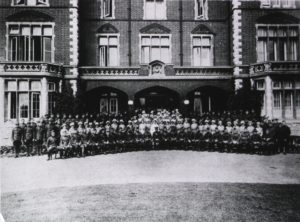

US Army Base Hospital No.33, Portsmouth, England: Medical and nursing staff (US National Library of Medicine. Copyright Free)

The connections with the United States was facilitated by the arrival of military and medical personnel during 1917 and 1918. With the deployment of troops to the battlefields of Europe planned by the United States, military and political figures used Portsmouth as a disembarkation and meeting point in the months after the declaration of war. Vice Admiral Sims would visit the city whilst the future President Franklin D. Roosevelt as Assistant Secretary of the Navy would arrive at Portsmouth in the spring of 1918. Indeed, Portsmouth would serve as an example of the international alliances that were formed during the war. A joint Allied unit of 7 destroyers, 31 patrol boats and 4 torpedo boats known as the ‘Portsmouth Force’ were based in the city to protect shipping and deter enemy activity.[2] Further army, navy and air bases as well as training centres in Hampshire ensured an increasing American presence in the city

The burgeoning ‘special relationship’ in Portsmouth was supported by the creation of a medical unit in the grounds of the Borough of Portsmouth Mental Hospital.[3] Base Hospital No.33 was organised from nearly 200 men and women serving at the Albany Hospital, Albany, New York in June 1917. A year later, many of these American citizens were assigned to No.33 and treated American troops injured on the Western Front. This included individuals such as Mattie Washburn, who was Chief Nurse at No.33 and who was from Fort Ann in upstate New York, who had moved from the hospital in Albany to serve in Portsmouth. With the destruction that the war created, the conflict also brought people to new context and new parts of the world.

Residents of Portsmouth provided support and events for hospital staff and their patients to entertain and to support morale.[4] From tea parties to concert nights, from opening up homes to recuperating soldiers to have a home-cooked mean to formal Rotary Club dinners, the Americans in Portsmouth were integrated into the city’s wartime civic culture.[5] The commanding officer of the unit, Dr Erastus Corning, was moved to remark in August 1918 in his correspondence back home:

“The people of Portsmouth are extending to us and to our patients every conceivable courtesy…”[6]

Red Cross Baseball. Part of the baseball grounds at the new Portsmouth base hospital. It is said to be the finest baseball diamond in England. (Library of Congress. Copyright Free)

Indeed, such was the growth of the facility during the summer of 1918 that Portsmouth was referred to in some local papers as ‘Little America’.[7] Base Hospital No.33 was turned into a home from home for patients who could garden, read and play sport on the site. A baseball diamond was also set

out for physical exercise and recreation.

This game was a highly significant import from the United States as whilst it served as a valuable pastime for troops it was also a means by which a form of soft diplomacy could be conducted in locations like Portsmouth. Charity baseball matches became a common feature in many towns across Britain and acted as a bridge between a foreign military presence and the public. In Portsmouth, the Mayor and Mayoress were the special guests for a baseball game played at Fratton Park on June 1st 1918. The game was styled as the United States Army against Canada and all proceeds were donated to charities across the country.[8] With the development of such strong ties, the celebrations of Independence Day which were held in the Guildhall in July 1918 was remarked upon as residents of Portsmouth making their American allies ‘feel at home’.[9]

Another prominent aspect of the presence of the United States within Portsmouth was the American YMCA which was set up in the summer of 1918 on Waltham Street in the city. This ‘American home’ for troops provided pastimes and food that would connect soldiers with home. American cigarettes and chewing gum were in supply at the site. Accordingly, this site would act as a connecting point between individuals based in Portsmouth and residents. It was described in accounts as, ‘a medium of introduction to the homes and hearts of English people’.[10]

The Superintendent of the American YMCA in Portsmouth was Rev. Dr. Amor Burr who also preached in the city’s churches. Dr Burr would thank the people of Portsmouth in his sermons for their kindliness and hospitality extended to soldiers.[11] Burr spoke about the need to defeat Germany and the importance of prayer. However, other American visitors in the city who spoke at churches and social events connected to the social and religious concerns in Portsmouth about alcohol. These Americans extolled the virtues of the growing interest in the United States for the banning of the sale of alcohol.[12] Therefore, the presence of Americans in Portsmouth brought far more cultural and social engagement between Britain and the United States than had existed before the war. It created new tastes, habits and values on both sides. Indeed, one soldier from New York was moved to remark about his conversion from coffee during his time in Portsmouth:

“That’s one thing I will say for the English, they do know how to make tea”.[13]

“One of the most splendid and comfortable of the big American hospitals in England, the Portsmouth Base Hospital, designed for about 2500 men.” (Library of Congress. Copyright free)

With the announcement of the Armistice in November 1918, Americans in Portsmouth celebrated alongside citizens as peace was greeted with excitement and relief. The end of the fighting was the swift dismantling of the American hospital and all staff had left the city by January 1919. Before this departure, there was time for goodbyes and Dr Corning took particular care to send thanks to all residents of Portsmouth and seasonal wishes in a Christmas message which also directed hope towards the future:

May the coming Peace bring with it a full development of the closer friendship and deeper understanding which the storm of war has brought about…[14]

The war transformed local and global contexts but it was a conflict that created as well as it destroyed. Amidst the wreckage of war, we can see how the arrival of Americans in Portsmouth brought people together who would otherwise have remained strangers. By examining these relationships we can create alternative histories of the conflict that can retell the war experience in Portsmouth.

Notes

[1] “Stars and Stripes,” Hampshire Telegraph, 6 July 1917

[2] Anon, The American Naval Planning Section (London, Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 1923), 43.

[3] “Use of Local Hospitals,” Hampshire Telegraph, Friday 31 May 1918.

[4] “Thought for the Wounded,” Hampshire Telegraph Friday 21 June 1918; “Entertainment of American Troop,” Hampshire Telegraph, Friday 16 August 1918.

[5] “American Guests,” Hampshire Telegraph, Friday 13 September 1918.

[6] Erastus Corning, “Correspondence,” Albany Medical Annals, vol. 39 (1918), 374-375.

[7] “U.S. Base Hospital 33,” Hampshire Telegraph, Friday 30 August 1918.

[8] “Great International Match: U.S. Army v. Canada,” Hampshire Telegraph, Friday 31 May 1918

[9] “Independence Day at Home,” Hampshire Telegraph, Friday 12 July 1918.

[10] “The American Y.M.C.A.,” Hampshire Telegraph, Friday 27 September 1918.

[11] “American Preacher at St. Thomas’s,” Hampshire Telegraph, Friday 27 September 1918.

[12] “Racy Temperance Speech,” Hampshire Telegraph, Friday 1 November 1918.

[13] “American News,” Hampshire Telegraph, Friday 25 October 1918.

[14] “An American Greeting,” Hampshire Telegraph, Friday 20 December 1918.

Comments are closed.