Damage to Market Place and Holy Trinity Church following a Zeppelin raid in June 1915. Source: East Riding Museums Service. Licensed under Creative Commons BY-NC-SA.

When we think of wartime bombing raids and attacks on civilians, we often conjure up images of ruined public buildings and homes during the Blitz of the Second World War. After all, this has become ‘one of the country’s most cherished and resilient national narratives’.[1] With public memories of the Blitz blending into broader evocations of national identity, the focus of these narratives has often been situated in the capital and only lightly touched upon the experiences of provincial towns and cities.[2] However, as is well documented, Hull – a port city on the north-east coast of England – suffered more than any location outside of London during the conflict, at the hands of Luftwaffe bombers.[3] Indeed, recent work on the legacies of Second World War bombing in Hull has revealed the continuing relevance of the ‘Hull Blitz’ locally, as a potent public memory and as a metaphor for the effects of London-centricity, be that in wartime or post-war news reporting, or today in the context of economic decline and the ‘levelling up’ agenda.[4]

What we should not forget was that Hull was also deemed a legitimate military target some 25 years before its Blitz, during the First World War, owing to its industrial facilities and docks. The city was hit in attacks by Zeppelin airships on eight occasions between June 1915 and August 1918, resulting in the deaths of 57 people. A further 151 were injured.[5] By focusing on places outside of London, we can perhaps problematise an assumed shared national experience of war in the twentieth century. Looking to the ‘coastal zone’ – to port cities such as Hull, as well as seaside resorts like Scarborough – provides an additional lens through which we can complicate and enrich this picture.[6]

Following the naval bombardment of Scarborough, Whitby and Hartlepool on 16 December 1914, the north-east coast became, in many ways, a militarised space. Scarborough, in particular, became a primary site for the projection of invasion fears: the beaches of the popular seaside resort town were strewn with barbed wire and sandbag roadblocks were installed on shopping streets.[7] Hull local government officials and businesses played an important role in the development of early-warning systems for the region. January 1915 saw the installation of steam-whistle alarms, known as ‘buzzers’, in Hull. On hearing the alarm – which could sound for as long as five minutes at a time – citizens were advised to find shelter away from the city streets and ‘extinguish all lights under their control which can be seen from outside’.[8] Working with the Hull city engineer, Hull brassfounders G. Clark & Sons Ltd. (based on Waterhouse Lane) provided Scarborough with a similar system later in the month, with experiments with sound levels and position taking place until early February. According to Scarborough’s borough engineer, the new siren was so loud, it was ‘sufficient to awaken the dead’.[9] Hull experimented with different versions of the early warning alarm throughout 1915. The effect of such experiments, and the sounding of the alarms in earnest, was a cause of consternation and anxiety for some residents.[10]

Despite there being only eight air raids on Hull during 1915-18, there could be as many as ten ‘buzzer nights’ in a single month. An alarm on 3 July 1915 was the tenth since early April of the same year.[11] The only ‘successful’ raid had been on 6-7 June, when more than twenty people were killed.[12] Anxiety that another raid could happen any time due to the frequency of alarms led some to panic. ‘Nervousness caused by the recent alarms in Hull’ was marked by the courts as the cause for an attempted suicide in July 1915.[13] In the case of Dorothy L. Sayers, now famous as a crime writer but a young modern languages teacher at Hull High School for Girls during 1915-17, doctors diagnosed her with a ‘nervous disease, resulting from nervous strain or shock… Eventually put down to shock of Zeppelin raids’.[14]

Hull’s maritime character factored into some complaints regarding ‘false’ alarms and confusion during actual alarms. The buzzers were not always audible above the everyday maritime traffic and dockside noise, thus heightening tension around the usefulness of early warning signals, apart from causing ‘needless alarm’.[15] Such conditions were not easy for civilians, who had to endure the death and destruction meted out by air raids, alongside the anxiety-inducing expectation of attack at any moment.[16] Given these unpredictable and often frightening circumstances, some local men in largely working-class districts of the city started ‘night patrols’, whose intent was to encourage the vigilance and resilience of their friends and neighbours in advance of potential enemy attacks. Hull appears to have been unique in this regard, with most towns and cities on the coast deferring such duties to the armed forces and the Special Constabulary.[17]

In the context of emergency legislation introduced at the onset of war in August 1914 – the Defence of the Realm Act (DORA) – an early form of civil defence was introduced. A blackout was imposed on towns and cities all over the country, with particular impetus being placed on coastal areas.[18] This meant that the local police, specifically the voluntary Special Constables, were empowered to keep order during air raid warnings and ensure all lights were extinguished. Hull recruited around 3,000 ‘Specials’ during the conflict, with many men replacing regular officers lost to the armed forces. However, in some areas of the city, this force was not deemed to be enough. Indeed, much like in other wartime industries, there were fluctuations in recruitment and shifting priorities in where officers were placed.[19]

The first voluntary ‘night patrols’ were formed shortly after the first Zeppelin raid on the city in June 1915. These men, many of them too old or too young to be eligible to fight at the front, took it upon themselves to unofficially police the darkened streets, waking up sleeping neighbours during alarms, ensuring lights were shaded and keeping a sharp lookout for Zeppelins in the skies above.[20] The patrols were organised on a street-by-street basis, with the volunteers generally focusing on their own neighbourhood. For those in areas close to docks – legitimate military targets in international law – the volunteers were seen to provide a source of reassurance. As a member of the Walker Street and Adelaide Street night patrol put it in July 1915: ‘[Previous] to our patrol commencing their duty (just now a week old) it was noticed that scores of women and children would not go to bed… After the patrol is on duty, the general cry is “I’ll go to bed now.”’[21]

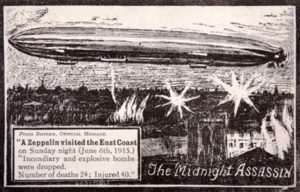

A postcard commemorating the 6 June 1915 Zeppelin raid on Hull and the East Coast. Source: East Riding Museums Service. Licensed under Creative Commons BY-NC-SA.

For the men, it was a chance to provide a patriotic, ‘manly’ service to the war effort, with very real implications for their friends and neighbours. This was evidenced by their hard work and commitment to working at unsociable hours in often inclement conditions.[22] A member of the Craven Street patrol wrote to the Hull Daily Mail on 14 July 1915 with this in mind: ‘I suppose that last week-end one of them spent most of his time in bed – he was thoroughly run down. Can it be wondered at; think, three or four nights every week? It is enough to kill horses, never mind men’.[23] The volunteers were also seen to embody a spirit of mutual aid and neighbourliness, conventions already well established in working-class communities in the early twentieth century and a source of pride:[24]

[The] whole success of the scheme is in its voluntary nature and local character. We are finding the true meaning of “neighbourliness,” and men who never previously spoke to one another now find in a walk and talk while on patrol that Mr So-and-So is a genial fellow, and not the unsociable chap we thought him. The whole street trusts the neighbour appointed for duty, and, as a fellow resident, that person naturally honours the trust.[25]

The patrols could even provoke a degree of class conflict, with detractors – including the Bishop of Hull, Francis Gurdon – seen as overlooking the good, patriotic intentions demonstrated by the patrolmen. Given that local elites had access to motor cars, they could escape the danger of Zeppelins by leaving the city. As a patrolman put it in September 1915:

You must remember that we cannot afford motor-cars to be able to clear out of it in case of danger. Oh, no, it’s the same thing over and over again – it’s the poor that helps the poor… Think of the poor souls who may be asleep and murdered in bed. What harm is done patrolling?[26]

The geography of the night patrols is particularly interesting, as they were clustered around the principle bomb sites that followed air raids, which tended to be close to the city centre, docks, timber yards and factories. The night patrols in the working-class residential areas of Porter Street, Walker Street and Campbell Street operated around the site of a number of civilian deaths and serious injuries, while Courtney Street was situated close to the Albert Dock.[27]

Clearly, Hull’s status as an important international port during the war was central to the experience of civilians. The atmosphere of the city, defined by the dockside sounds of workers and ship’s hooters, could crowd out the vital air raid sirens introduced early in 1915. Coming increasingly under fire from Zeppelins, ordinary people sought reassurance and a source of resilience which, when police numbers were lacking, took the form of self-organised civil defence ‘from below’.[28] Voluntary night patrols present us with a startling example of civilian agency during the First World War, where primarily working-class people looked out for their neighbours. Though their intentions were often defined in highly gendered terms, we can see such schemes as examples of a local form of patriotism, where the defence of the city and its citizens was stressed above that of nation and empire.[29]

Notes

[1] James Greenhalgh, ‘The Threshold of the State: Civil Defence, the Blackout and the Home in Second World War Britain’, Twentieth Century British History, 28 (2) (2017), 186-7.

[2] Adam Page, Architectures of Survival: Air War and Urbanism in Britain, 1935-52 (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2019), 95-6.

[3] David Atkinson, ‘Trauma, Resilience and Utopianism in Second World War Hull’ in Hull: Culture, History, Place, eds. David J. Starkey, David Atkinson, Briony McDonagh, Sarah McKeon and Elisabeth Salter (Liverpool: Liverpool University Press, 2017), 239.

[4] James Greenhalgh, ‘History of Hull: Walking in Hull Pt. 2 – A North East Coast Town’, The Half Life of the Blitz on Hull project blog, 2 February 2022, https://thehalflifeoftheblitz.blogs.lincoln.ac.uk/2022/02/02/history-of-hull-walking-in-hull-pt-2-a-north-east-coast-town/ (accessed 9 February 2022); Paul Swinney, ‘Does the Levelling Up White Paper measure up?, Centre for Cities blog, 3 February 2022, https://www.centreforcities.org/levelling-up/ (accessed 9 February 2022).

[5] Arthur G. Credland, The Hull Zeppelin Raids 1915-1918 (Oxford: Fonthill, 2014), 108-11.

[6] Isaac Land, ‘Doing Urban History in the Coastal Zone’ in Port Towns and Urban Cultures: International Histories of the Waterfront, c.1700-2000, eds. Brad Beaven, Karl Bell and Robert James (London: Palgrave Macmillan, 2016), 265-282; Michael Reeve, Bombardment, Public Safety and Resilience in English Coastal Communities during the First World War (Cham: Palgrave Macmillan, 2021), Ch. 8.

[7] Reeve, Bombardment, Ch. 4.

[8] Credland, Hull Zeppelin Raids, 17.

[9] Scarborough Library, Uncatalogued Bombardment Correspondence, Harry W. Smith to C.M. Shaw, 2 February 1915.

[10] Reeve, Bombardment, 85-7.

[11] Imperial War Museum, Dept. of Documents, K 81705, ‘Zeppelin Warnings in Hull’.

[12] Credland, Hull Zeppelin Raids,108.

[13] ‘Upset by Alarm Signals: Hull Woman’s Attempted Suicide’, Hull Daily Mail, 15 July 1915, 3.

[14] Quoted in Susan R. Grayzel, At Home and Under Fire: Air Raids and Culture in Britain from the Great War to the Blitz (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2014), 62.

[15] J. Saunders, ‘Cannot the Authorities Take Action’, Hull Daily Mail, 8 July 1915, 2.

[16] Paul K. Saint-Amour, Tense Future: Modernism, Total War, Encyclopaedic Form (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2015), 7, 17; ‘War Shock in the Civilian’, The Lancet, 4 March 1916, 522.

[17] Reeve, Bombardment, 216-27.

[18] See ‘Defence of the Realm Regulation 11, as to Extinguishing or Obscuring Lights’ in Alexander Pulling, ed., Defence of the Realm Manual, 5th Edition (London: His Majesty’s Stationary Office, 1918), 89-91; Jerry White, Zeppelin Nights: London in the First World War (London: Vintage, 2014), 50; Reeve, 343.

[19] ‘Hull “Specials” Gift to Ex-Chief Constable’, Yorkshire Post, 15 December 1922, 9; Hull Daily Mail, 21 November 1918, 2; Mary Fraser, Policing the Home Front 1914-1918: The Control of the British Population at War (London: Routledge, 2019), 31.

[20] ‘The Air Raids on the East Coast: Are Street Patrols Illegal?’, Hull Daily Mail, 7 September 1915, 4.

[21] P. Whitlam, ‘The Use of Patrols’, Hull Daily Mail, 14 July 1915, 2.

[22] ‘News of “Specials” in Brief’, Police Review, 22 January 1915, 38; ‘Our Day of Rest’, The Bystander, 17 February 1915, 30; ‘Our Captious Critic’, Illustrated Sporting and Dramatic News, 20 February 1915, 18.

[23] ‘Street Patrols: Craven-street’, Hull Daily Mail, 14 July 1915, 2.

[24] Justin Davis Smith and Melanie Oppenheimer, ‘The Labour Movement and Voluntary Action in the UK and Australia: A Comparative Perspective’, Labour History, 88 (2005), 106; Geoffrey Finlayson, Citizen, State, and Social Welfare in Britain 1830-1990 (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1994), 137, 157; Paul Johnson, ‘Credit and Thrift and the British working class, 1870-1939’ in The Working Class in Modern British History: Essays in Honour of Henry Pelling, ed. Jay Winter (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1983), 160, 164.

[25] ‘Paid Night Patrols’, Hull Daily Mail, 16 July 1915, 6.

[26] ‘If Patrolling is Stopped?’, Hull Daily Mail, 9 September 1915, 2.

[27] Reeve, Bombardment, 224.

[28] Reeve, Bombardment, Ch. 5.

[29] Brad Beaven, ‘The Provincial Press, Civic Ceremony and the Citizen Soldier during the Boer War, 1899-1902: A Study of Local Patriotism’, Journal of Imperial and Commonwealth History, 37 (2) (2009), 207-28; Reeve, ‘‘The darkest town in England’: patriotism and anti-German sentiment in Hull, 1914-19’, International Journal of Regional and Local History, 12 (1) (2017), 42-63.

Well done Michael, glad to see you’re promoting your book & hope it does massively well. Very best wishes, Mary Fraser

An interesting article, Michael. My grandfather was born down Campbell St (a huge residential street) that no longer exists except for the very beginning off Walker Street. My great-grandfather was married down the street at the large church, I believe too. The street got swallowed up when the Daltry Street flyover was constructed in the city. Well done, on a fascinating insight into Hull during WW1. Well done on your excellent book too.