Vittore Carpaccio, “Hunting on the lagoon,” ca. 1490. [Getty Museum: public domain image] According to the Getty’s caption, these Venetian archers “use clay pellets rather than arrows in order to stun the birds and not damage their plumage.”

For this, the fiftieth post at the Coastal History Blog, I thought it would be a good time to step back and reflect. Even subtracting the nine guest posts, I suspect that a word count of what I’ve posted here under my own name would amount to a short monograph (in installments). This may seem like an odd way to spend my time. Maybe it would help to share some background that most of you have never heard from me, and which I’ve certainly never set down in writing: What brought me to invent the term “coastal history” in the first place, and what motivated me to establish the #coastalhistory hashtag and maintain this online presence, on Twitter and through the blog, for seven years.

David Octavius Hill and Robert Adamson, “St. Andrews, Fishergate, Women and Children Baiting the Lines,” ca. 1843-1847. [Getty Museum: public domain image.] I discuss this image in War, Nationalism, and the British Sailor, pp. 143-144.

I didn’t begin my career with any special sense that the term “coastal” was important to me. I was trying to figure out what to say about sailors in port. Another group that interested me from the beginning was the women on or around the waterfront who were an important part of the picture, yet who didn’t necessarily get their feet wet. At the time, I thought I was squaring the circle between Marcus Rediker’s early work, which emphasized how sailors were “men apart,” transfigured by the remoteness of sea life and the experience of life on ship, and Linda Colley’s famous book on popular patriotism in wartime.[1] I became especially interested in sailors who attempted to claim some control over how their story was told, through petitioning, autobiography, or other means.

David Octavius Hill and Robert Adamson, “Willie Liston, Redding the Line,” ca. 1843-1847. [Getty Museum: public domain image.] I discuss this image in War, Nationalism, and the British Sailor, pp. 147-148.

John Thomas Smith, “Joseph Johnson,” 1817. [British Library: public domain image.] I discuss Johnson and his unusual headgear in my article “Bread and Arsenic,” pp. 100-101.

The turning point for me came, instead, almost ten years later. In January 2005, I was at the American Historical Association meeting in Seattle. It was in one of those sessions that the conference organizers know will be so well-attended that they book a ballroom for it. For this one, every seat was taken and people were standing in the back and along the sides. The session was on Atlantic History, with a panel of luminaries including Joyce Chaplin and Philip Morgan.[4] Digging up the PDF of the conference program, which is still available online, I am a bit surprised to find that the title of the panel was “Atlantic History: A Critical Reassessment.” That’s probably what drew me in; I’d published my own critique of Atlantic History in 2002.[5] Maybe my ear wasn’t properly attuned, but I don’t recall a lot of introspection on the part of the panelists, or even debate between them.

In the question and answer session, a woman stood up—I seem to remember her as tall—and demanded that the panel clear up her dilemma. She was, like most of the scholars her age there, on the market. “I work on Native Americans, trade and diplomacy in the Great Lakes,” she said. “How am I supposed to make my project an Atlantic project?” That was her whole statement, but she uttered those lines like an accusation, as if she had booked the trip and come all the way to Seattle for the sole purpose of confronting this panel with that question. One panelist replied benignly, “You don’t have to, and shouldn’t feel you need to.”

This was true, of course, but it evaded the real question. This was an era in the profession when no one could find much to say as a critique of Atlantic History, except possibly that its remit was too small. (As late as 2010 I was still meeting PhD candidates who would ask me with great seriousness, “My project tracks a commodity across four continents over two centuries. Do you think that is too narrow a focus?”) The questioner in the ballroom was asking whether her choice to “merely” work on Native Americans in the Great Lakes, using the natural frame of reference and priorities that emerged from her source material, had put her on a path where she’d earned a doctorate, but she’d be best off leaving academia altogether. To use a term that only became widespread a bit later, was precarity—in a string of uncertain part-time teaching posts—the best she could expect now?

Meanwhile, Atlantic History could pack a ballroom and threaten to trigger a fire code violation at the AHA. Search committees often start with an expectation that’s in line with what they consider the latest trends; projects outside of those bounds may not even be intelligible to them. Sometimes what we call “articulate” is just a person who’s expressing themselves in the shorthand that we’ve come to know and respect. Like me, the historian who worked on Native Americans was thinking about her watery project primarily in terms of the adjacent, the local, and the domestic. There’s nothing intellectually illegitimate about that, and nothing inherently boring or insignificant about such a project, yet in 2005, it wasn’t what people were ready to hear.

It’s probably worth interjecting at this point that fashionable approaches and subject matter are fashionable for a reason. A lot of worthwhile things came out of Atlantic History, in curricular terms and otherwise. That said, part of the frustration here is that a worthwhile project that’s well-aligned with the temper of the times opens doors, whereas other worthwhile projects… well, are you familiar with the expression “wouldn’t give someone the time of day”? One search committee, which somehow had shortlisted me as worthy of their time in Seattle, tried to terminate my interview halfway through the 20-minute time slot.

After all my interviews were over (I only had two, or maybe I should say I had one and a half), I took a day trip to Portland on the train. This had been my first experience of the Pacific Northwest; I’d been out on the water for a harbor tour in Puget Sound a day or two before, and now I watched the hills and fjord-like waterways through the train window in the mist. That was, very nearly, the day that I turned away from a serious research and writing agenda. “I had something clever to say about nationalism at the exact moment that every search committee wanted transnationalism”: That’s a complaint, but it would be petulant to make it a mission.

At the time, I had a tenure-track position at a small state university in Texas, albeit one with a 4:4 teaching load. There were ways to present an adequate portfolio of publications for tenure and then pivot to a different set of goals. I definitely had some potential role models. There are experts on Dutch Golden Age portraiture who become college presidents. One of my peers from grad school went from studying some aspect of Byzantine church history to leading an Honors College in southern California structured around a Great Books curriculum, and he takes the students out camping in the desert to discuss the meaning of life under the stars. For that matter, we’ve all come across the “recovering academics” who discover they have an unexpected gift for fundraising, or running an NGO. I would have stayed on in academia. I think. But for sure, I would have redirected my energies.

This felt like a settled decision, and the right one. The train kept moving south. I found myself thinking about the other young historian, though. I had set my own grievances aside, only to find that hers still seemed quite immediate. What she had accomplished, quite by accident, was to make it hard to see my problem as uniquely mine. Giving up on my research agenda felt like also giving up on hers, which didn’t feel acceptable. It was as if some little piece of her anger had flown off like shrapnel and now it was lodged in me, a radioactive little piece of uranium.

I’d noticed from the beginning that my research area didn’t have a good name—as Mary Conley had observed to me years before, it was like diving into an untouched and undefined intellectual space—but for the first time I could see how this lack of vocabulary set up a lack of recognition, and the lack of recognition had really profound consequences. To respond in a more practical way than scolding an AHA panel, though, required a better grip on the scale of the problem. How many scholars were in the same fix? There was, possibly, a whole flotilla of ugly duckling projects that were “not oceanic enough” in 2005. Unlike the practitioners of Atlantic History, though, we didn’t have a way to issue a call to action—or even a call for papers.

Jacoba van Heemskerck, “Composition: Fjord” (late nineteenth or early twentieth century). [Met Museum: public domain image.]

That is the context for the hopeful paragraph that comes almost at the end of “Tidal Waves: The New Coastal History,” a review essay which was published in the Journal of Social History two years later.

“Oceanic” history was always a metaphor; how many historians ever wrote about salt water? Coastal history is a more productive, and instructive, metaphor. Coastlines would not exist without their proximity to the ocean, but their character is not determined solely by the ocean’s action. Coasts may form bulwarks of resistance to the waves, as in the case of coral reefs or towering cliffs. Yet there are messy, intermediate places like tidal flats and brackish estuaries. There are also quiet coves and inlets, connected to the ocean but only gently shaped by it. Rivers and lakes form networks of internal coastlines that bear comparison with the ocean’s rim. Coasts are also, sometimes, engineered or artificial environments that may penetrate urban space. In their diversity, and in their ever-changing nature, coasts parallel the diverse experiences of human beings in their confrontation with water, and each other. Some people are knocked over, or borne away on powerful currents. Others just leave footprints in the sand. The coastal continuum admits many fine gradations and strata of experience that “oceanic” history threatens to wash away.[6]

There is still, in that paragraph, just a little residual sense of me staring out the train window and wondering about the “quiet coves and inlets.” Yet “Tidal Waves” is also, permanently frozen in time, the angry rejoinder to everything I saw and experienced at the AHA in 2005.

As the place where the term “coastal history” was introduced, I see that “Tidal Waves” is already my second-most-cited publication. I have mixed feelings about this. I don’t think it’s unusual for the first hints of a new paradigm to appear in the form of an expression of discontent or rebellion, but I wish that Peter Stearns, the editor of JSH, had picked up the phone and told me, “Listen, we think you may be on to something here, but why not start over, begin with that paragraph about coasts, rivers, and lakes, and then tell us who’s doing worthwhile work that follows through on the promise of that paragraph?” Instead, “Tidal Waves” was published without any dialogue with JSH, and with no changes whatsoever.

That was a remarkable act of faith in an unknown junior scholar (though known to them; JSH had published my article “Bread and Arsenic” two years earlier). I can only conclude that Stearns, and the editorial board at JSH at the time, shared at least some of my sentiments that Atlantic history in its current form was oversold, and deserved a little comeuppance. The net result, though, was that coastal history made its debut in a critical piece that made its frustrations clear, but only touched on a way forward at the very end.

I did feel I had cleared the ground enough that it was no longer necessary to be negative. I wrote a chapter about coastal history which was, in effect, the missing second half, the upbeat complement to “Tidal Waves” that offered a constructive vision and found fault with no one. This formed the original introduction to my monograph, War, Nationalism, and the British Sailor, and as such, it would have appeared in 2009. Instead, that chapter never saw the light of day. I drew peer reviewers who didn’t see the point of it, and instead wanted me to face backwards, towards old feuds and the seemingly endless need to differentiate what I did from a style of maritime and naval history that really had nothing to do with my interests at all.

Edouard Baldus, “Entrance to the Port of Boulogne,” 1855. [Met Museum: public domain image] The Met’s caption remarks of the “elegantly engineered jetties that guided vessels from the English Channel past the scruffy shoreline and into the protected harbor alongside the Boulogne station.”

Building a blog

If “Tidal Waves” was a demolition job, then the Coastal History Blog has been seven years of blueprints and architectural drawings. It was ridiculously wide-ranging (there, I said it so you wouldn’t have to), but this was a “proof of concept” exercise. My hope was that readers could imagine what a coastal history conference would look and sound like, for example.

Within about 48 hours of delivering the keynote at the “Port Towns and Urban Cultures” conference, I was thinking about how to build bridges to environmental historians, as well as to historians of the beach and of leisure. At the time, I knew literally no one who did any of those things, but you can see the outreach, beginning in my earliest four or five blog posts in 2013.

Overall, I saw the blog as advancing three strategic goals. The first was to engage people with already formulated research agendas who might find coastal history meaningful, attractive, or useful… and ideally all three of those! It took a while to gain traction, but after the first two years of the blog, about half of the posts were guest posts.

The second goal was to encourage interaction and participation by formulating some possible “coastal questions” myself, to suggest the intellectual potential of the approach beyond just “we need an alternative to what’s out there.” Asking the coastal questions ought to lead to articulating coastal propositions; even ones that turned out to be incorrect would have the necessary effect of creating some productive debates and, with luck, provoking better counter-propositions. I wrote about the “coastal-urban forms” (urban foreshore, urban offshore, urban estuary), explored different territory in “The Tolerant Coast,” and published a review essay, “Antagonistic Tolerance and Other Port Town Paradoxes.”[7] All of these were, in one sense or another, elaborations of earlier blog posts touching on those themes.

The third goal was to challenge others to start asking themselves what coastal history had to offer if applied to their own specialty, time period, or region. Julia Leikin, David Worthington, and Michael Talbot have gone on to do just that.[8] An active pursuit of the first two goals, I hoped, would gradually have the effect of accomplishing the third as well, since noticeable gaps would start to appear between what I was featuring in the blog and a shadowy list of “ought to have” and “what about…” that would occur to others. So much good scholarship begins with a moment of puzzlement or annoyance.

Here are links to a couple blog posts that convey something of the “middle period,” as I began meeting people I wouldn’t otherwise have found without the blog (or who found me because of the blog):

Coastal History: Who, What, and Why? (guest post on David Worthington’s blog)

Conference (and Roundtable!) Roundup)

As I proceeded with the networking, I did gradually become aware of some other scholars who had floated potential terms that corresponded, to varying degrees, with coastal history. “Terraqueous” history is one example.[9] The restless sense of a need for new language has been clear for some time. Typically, these alternative frameworks have made claims only about a single region, or stopped at the “thought-piece” stage. What the blog enabled me to do, though, was to carry out the strategic outreach to suitable groups of potential allies, and write up the results so people could see what was happening and decide whether they wanted to affiliate. Twitter gave me the platform for a disciplined social media strategy to back up the blog. I saw an entrepreneur quoted once as saying that the people who get things done are the ones who are capable of “being impatient in the long term.” For better and for worse, that describes my personality.

A famous physicist liked to say, in considering experimental design and the validity of results, “There’s no one easier to fool than yourself.” Obviously, I had a vested interest in imagining that I’d come up with something useful. If there was no constituency for coastal history, the blog’s reception could have established that beyond a doubt, in which case it would be time to wrap things up for good.

The vast penumbra

The New Coastal History volume, edited by David Worthington, came out ten years after “Tidal Waves” first appeared. My chapter in New Coastal History was entitled “The Urban Amphibious.”[10] I will always be proud that my brief amateur’s sketch of likely coastal futures in an era of sea-level rise, contained in that chapter, tracks pretty closely with Jeff Goodell’s full-length treatment in The Water Will Come; the two books were published within weeks of each other in 2017.[11]

I don’t think I need to belabor the evidence that the 21st century is the century for asking the coastal questions. Yet, as I explain in the essay, my reasons for discussing those contemporary and futuristic examples was in large part a thought experiment to clarify some problems of definition. Consider the items on this list. What do they have in common?

- land “reclamation” through the addition of sand (Dubai; Singapore)

- amphibious architecture and “sponge cities”

- community-level adjustment to sea level rise

- construction codes and zoning in hurricane-prone regions

- “debris studies” (floating plastic etc.)

- desalination plants

- oil spills

- real estate speculation on the coast

- seasteading

- surfing

- illegal waterborne migrants

All are undeniably coastal and bound up with watery worlds, yet they don’t line up well with academic discourse around “the maritime” (even though several of these activities are old enough to have spawned a historiography of their own).

Is there a term for watery subject matter that refers to things that only really get started where the maritime leaves off? Gérard Le Bouëdec coined a potentially very useful word, “paramaritime,” without fully defining it or, in my view, exploring the implications. His interest was captured by pluriactives (sailor-blacksmiths, and so forth) that turned up in the Breton parish records. In a publication that’s out now in eBook form, and will be available in hard copy next month, I furnish Le Bouëdec’s term with an explicit definition, I think for the first time anywhere (it doesn’t seem to be defined in French dictionaries, any more than in English ones):

A working definition of the paramaritime, drawing on conventional uses of the para- prefix, might look like this: ‘Occurring beside, around, or between maritime areas; containing elements not usually regarded as maritime; analogous or parallel to maritime entities (spaces, cultures, occupations, activities), but separate from or going beyond them’. The paramaritime, then, is pertinent for shallow waters (bays, coves, estuaries, firths, fjords, inlets), but it also speaks to interstitial watery spaces (straits and portages; reticulated systems of lakes, rivers, or inland seas; archipelagoes or island clusters).[12]

Although this statement, intentionally, mirrors of some my language from “Tidal Waves” (which I quoted earlier in this blog post), and is faithful to Le Bouëdec’s basic usage, I also try to stretch the term out and broaden its utility with the reference to not just occupations and activities, but also to spaces and cultures. In the chapter, I really put the term through its paces for the early modern period (this edited volume dealt with the period 1400-1800), touching on the following:

- parades, processions, and diplomatic sendoffs

- the port city as spectacle (whether as a panoramic triumph of urban planning, or as a marvel of cosmopolitan space)

- strategies of containment (quarantine, extraterritorial enclaves, policing)

- methods of mediating and regulating contact zones (shahbandars, consociational governance, “country marriages,” the politics of recognition for minority languages and religions

- hybrid cultural forms, women as culture brokers in “mixed” marriages, ambiguous shrines and so-called “syncretism”

The contrast between these lists and a list of the more “familiar” maritime topics suggests an interesting generalization. On watery subject matter, we have a whole pattern of established categories of scholarship that are occupationally- or vocationally-centered: the work of fisheries, the work of shipyards, the work of merchant shipping, the work of navies. Meanwhile, the worshippers at ambiguous shrines might be merchants or sailors, but their worship, and the attitudes they bring to that worship, are not inherently economic or vocational events. Similarly, to turn to more modern examples, there are a few professional surfers, but the great majority of practitioners are doing it in their leisure time. And whether you’re embarking from Vietnam or Cuba in the twentieth century, or across the Aegean in the present day, no one gets paid to be an illegal waterborne migrant. Suspending the assumption that the subject matter needs to be occupationally- or vocationally-centered is fundamentally reorienting.

Auguste Rodin, “Beside the Sea,” 1907. [Met Museum: public domain image.] This rather unusual sculpture captures a meditative sense of wonder at the embodied contact with sand.

Conclusion

I’m a practical person. Names and labels wouldn’t interest me, except that I have personally witnessed the consequences of doing work in a nameless field. Over the last seven years, I’ve collected still more examples of those consequences. From film studies, Fiona Handyside blogged about her experience approaching publishers with her idea for a book about “the representation of beaches in the cinema” only to find that

I got together a book proposal, carefully worked through, with many structures rejected before I thought it was perfect. The response was outright rejection from the publisher, my sample chapter not sent out to readers, and the suggestion that it would better to have a book more generally about space, as beaches was ‘too niche’… I was thrown into a tail spin – this represented three years of work!

Reading this brings me right back to that confrontation in the ballroom in Seattle. Handyside’s story has a happy ending in the sense that her book was eventually published elsewhere.[14] I can’t help but wonder, though: How many projects that would have interested the readers of this blog have withered on the vine? It isn’t always feasible to regroup after those initial rounds of rejection or incomprehension. Many of us know this feeling— for years, we’ve been the proverbial round peg in the square hole. It’s exhausting. It’s infuriating. As I’ve explained here, I almost quit myself.

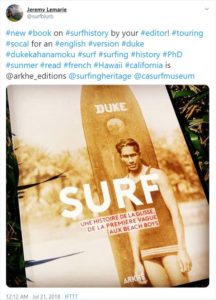

When I say that a number of scholars are doing coastal history or coastal studies already, without being aware of it, I never meant to be mysterious. But consider this tweet, which makes a valiant effort to supply good hashtags for a new book on the history of surfing.

What does it mean to spend years writing a book, and then being at a loss for appropriate hashtags and keywords to help people find it?

For quite a few years there, I enjoyed the rather empty privilege that coastal history was whatever I said it was, for the simple reason that I was the only person using the term. I recognize, as with startups and dot coms, that there’s a risk of “founder’s syndrome” for me. I could easily spend the rest of my life making ill-tempered interventions, trying to police the usage of a term that I invented. I’m not going to fall into that trap. I recognize that coastal history has reached escape velocity, and if you hold onto a rocket after you’ve ignited it, all you get is a burned hand.

I don’t know if the Coastal History blog will make it to the 100th post, but my intention was always for the blog to serve as a mode of convocation or summoning, to help bring that missing community of scholars into being. What I could see this year, with the WebEx calls moderated by David Worthington, the many contributions to the Zotero shared library, initiated by Giacomo Parrinello, which has passed 300 items, and the growing spreadsheets of researchers and interests resulting from the Google Form devised by Mel Bassett, is that at least this portion of my work is done.

I have been fortunate to meet many fascinating scholars and people outside academia through my work on this blog, and I’ve often been surprised by the approaches they take, or the opportunities they have spotted. I recognize that this is only the beginning. Others will use the conceptual toolkit in ways I didn’t anticipate. Others will make improvements that I couldn’t have thought of myself. Coastal history will grow in directions I wouldn’t have taken it, especially in the hands of early career scholars, but that was always my intention. On the train to Portland, my initial vision was very specifically of something big enough to include lots of different projects, including projects devised by scholars who were unlike me. If it isn’t that big, then I was wrong in the first place.

David Octavius Hill and Robert Adamson, “James Linton,” ca. 1843-1847. [Getty Museum: public domain image.]

Notes

[1] Marcus Rediker, Between the Devil and the Deep Blue Sea: Merchant Seamen, Pirates and the Anglo-American Maritime World, 1700 – 1750 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1989); Linda Colley, Britons: Forging the Nation, 1707-1837 (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1992).

[2] Isaac Land, “Bread and Arsenic: Citizenship from the Bottom Up in Georgian London,” Journal of Social History vol. 39, no. 1 (Fall 2005), 89-110; Isaac Land, War, Nationalism, and the British Sailor, 1750-1850 (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2009); Isaac Land, “Patriotic Complaints: Sailors Performing Petition in Early Nineteenth-Century Britain,” in Fiona Paisley and Kirsty Reid, eds., Critical Perspectives on Colonialism: Writing the Empire from Below (London: Routledge, 2014), 102-120; Isaac Land, “Epilogue: Gendered Virtue, Gendered Vigor and Gendered Valor,” in Michael Brown, Anna Maria Barry, and Joanne Begiato, eds., Martial Masculinities: Experiencing and Imagining the Military in the Long Nineteenth Century (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2019), 255-266.

[3] Mary A. Conley, From Jack Tar to Union Jack: Representing Naval Manhood in the British Empire, 1870–1918 (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2009).

[4] I distinctly remember Carla Rahn Philips on the panel, but I do not see her listed; is it possible she was substituting for someone else who fell ill or missed their flight?

[5] Isaac Land, “The Many-Tongued Hydra: Sea Talk, Maritime Culture, and Atlantic Identities, 1700-1850,” Journal of American and Comparative Cultures vol. 25, nos. 3-4 (December 2002), 412-417. As Brian Rouleau remarked to me in 2009, “Absolutely no one picked up on that piece, did they?”

[6] Isaac Land, “Tidal Waves: The New Coastal History,” Journal of Social History vol. 40, no. 3 (Spring 2007), 731-743.

[7] Isaac Land, “Antagonistic Tolerance and Other Port Town Paradoxes,” Forum Navale vol. 72 (2016), 78-101; Isaac Land, “Doing Urban History in the Coastal Zone,” in Brad Beaven, Karl Bell, and Rob James, eds., Port Towns and Urban Cultures: International Histories of the Waterfront, c. 1700-2000 (London: Palgrave Macmillan, 2016), 265-281; Isaac Land, “The Tolerant Coast,” in Charlotte Mathieson, ed., Sea Narratives: Cultural Responses to the Sea, 1600-Present (London: Palgrave Macmillan, 2016), 239-260.

[8] Julia Leikin, “Across the Seven Seas: Is Russian Maritime History More Than Regional History?” Kritika: Explorations in Russian and Eurasian History vol. 17, no. 3 (Summer 2016), 631-646; David Worthington, “Ferries in the Firthlands: Communications, Society, and Culture along a Northern Scottish Rural Coast, c.1600 to c.1809,” Rural History vol. 27, no. 2, (2016) 129–48; Michael Talbot, “Separating the Waters from the Sea: The Place of Islands in Ottoman Maritime Territoriality during the Eighteenth Century,” Princeton Papers: Interdisciplinary Journal of Middle Eastern Studies vol. 18 (2017), 61–86.

[9] Alison Bashford, “Terraqueous Histories,” Historical Journal vol. 60, no. 2 (June 2017), 253-272.

[10] Isaac Land, “The Urban Amphibious,” in David Worthington, ed., The New Coastal History: Cultural and Environmental Perspectives from Scotland and Beyond (London: Palgrave Macmillan, 2017), 31-48.

[11] Jeff Goodell, The Water Will Come: Rising Seas, Sinking Cities, and the Remaking of the Civilized World (New York: Little, Brown, 2017).

[12] Isaac Land, “Port Towns and the ‘Paramaritime’,” in Claire Jowitt, Craig Lambert, and Steve Mentz, eds., The Routledge Companion to Marine and Maritime Worlds, 1400-1800 (forthcoming July 2020; I do not have page numbers for this yet).

[13] Land, “Port Towns and the ‘Paramaritime.’”

[14] Fiona Handyside, Cinema at the Shore: The Beach in French Film (Oxford: Peter Lang, 2014).

[15] I am especially happy when I come across a piece of scholarship that approaches coastal themes in a manner so unique that the effect on the reader is slightly disorienting (or reorienting): Michael Pearson, “Littoral Society: The Case for the Coast,” The Great Circle vol. 7, no.1, (1985), 1–8; Greg Dening, Mr. Bligh’s Bad Language: Passion, Power and Theatre on the Bounty (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1994); Victoria Carolan, “The Shipping Forecast and British National Identity,” Journal of Maritime Research vol. 13, no. 2 (2011), 104-116, Karl Steel, “Insensate Oysters and Our Nonconsensual Existence,” in Steve Mentz, ed., Oceanic New York (Brooklyn, NY: Punctum Books, 2015), 79-92.

Great! Have to read more about ‘your’ coastal history!