Commemorating the maritime heritage of the southern tip of Manhattan, inside Fulton Street subway station. All photos by Isaac Land, December 2017

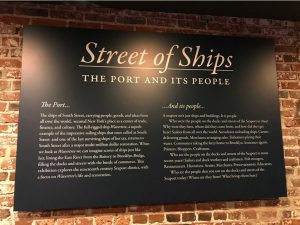

On a recent trip to New York City, I visited South Street Seaport Museum (SSSM), located almost in the shadow of the Brooklyn Bridge. There is more maritime heritage associated with this location than I can easily enumerate here.[1] It was once the “Street of Ships” where transatlantic steamers and passenger liners anchored. It also faces the East River side of Brooklyn, itself a world-class port in the era before container shipping.

I’ve addressed public history and museums once before in this blog (“Maritime Heritage and Social Justice,” back in 2015, about the challenges of representing the history of the slave trade in French ports). South Street was, and is, also a heritage battleground of sorts. Its intriguing story is told in James M. Lindgren’s recent book, Preserving South Street Seaport: The Dream and Reality of a New York Urban Renewal District.[2] From the beginning, the intention was for SSSM to have outposts scattered through the neighborhood, rather than occupying a self-contained enclave. The initial decision in the late 1960s to avoid a “living museum look” set up a tension, as the folk singer and activist Pete Seeger put it, between “boats and boutiques” that persists to this day. SSSM was, undeniably, a breakthrough project in vernacular heritage preservation. Its tantalizing slogan, “the museum is the people,” sent it on a distinct and perhaps quixotic path, earning it both praise and criticism, and resulting in administrative and financial headaches that persist to this day.

It’s too easy, in any historical inquiry, to take the final outcome as obvious and reduce our task to tracing the causes that led to it. Yet in the case of South Street, there is ample evidence elsewhere around New York City’s waterfront of the paths not taken, of alternative ways to “preserve.” On the Brooklyn side, East River State Park is a simple, bare area of seven acres which preserves a patch of green space for the use of the public. A few small interpretive plaques explain the site’s history as part of a vast rail-marine terminal—once extending along the waterfront for seven blocks, but now demolished—developed by the sugar industry, and later used to warehouse flour. The plaques are easily ignored, and the park feels minimalist. As far as I could tell in my wintertime visit, it is developed only to the extent that children could play there, or it might serve as a convenient venue for amateur sports events or a farmer’s market. This might seem like a threadbare approach to preservation, but perhaps the priorities of the current residents factored into the decisions here. East River State Park’s web page notes that “the park offers native meadow plantings among the historic rail yard remnants; passive recreation; picnicking and barbecues.”[3] It also offers an excellent prospect of the Empire State Building across the water, and no one has to enter private property or pay a fee to enjoy that view.

East River State Park in Brooklyn, facing midtown Manhattan. For an interesting contrast, compare George Bellows’ painting Men of the Docks. The artist stood on the Brooklyn waterfront perhaps a few blocks south of my location here, in the year 1912

A completely different concept for preserving Brooklyn’s waterfront was to save one of the large warehouses from demolition and re-create the sights and sounds of the old harbor inside it, using Walt Disney-style animatronics. One can only imagine the deafening chorus of sea chanties to replace “It’s a Small World After All.”

That particular approach never got off the ground, but a final instructive contrast to South Street Seaport is the National Parks of New York Harbor, an eclectic set of 11 discontinuous sites administered by the U.S. government, including the Statue of Liberty, the Ellis Island Museum of Immigration, and the African Burial Ground National Monument. It was hardly a foregone conclusion that South Street Seaport wouldn’t be absorbed into this impressive constellation of historic sites. Indeed, as New York’s hub of watery transport, the docks along South Street received people and goods from around the world. In the New Coastal History volume, Johnathan Thayer recounts how the Seamen’s Church Institute undertook a fierce campaign of “military entrenchment” on and around South Street in the hopes of intercepting just-paid-off sailors before they could fall into the hands of crimps, tavern-keepers, boarding houses of ill repute, and sex workers.[4] (Some of their more colorful methods included a floating Gothic church docked at the pier, and eventually a million-dollar high-rise Sailor’s Home complete with a “boozeless bar,” a savings bank, a post office, a gym, and a library.) More pertinently for the story of American national identity and lieux de mémoire, the South Street neighborhood was the place where those processed at Ellis Island set foot on the American mainland, and made arrangements to continue their journey by train.[5]

These alignments and exclusions have consequences, of course. Today, the Statue of Liberty and Ellis Island have a merged Twitter account with almost 30,000 followers, while the South Street Seaport Museum’s Twitter account has less than 4,000 followers, and many of my international readers are hearing about South Street for the first time here.[6]

Why SSSM took the particular form that it did, then, requires some explaining. Each alternative or option, of course, is premised on a somewhat different answer to the underlying questions. Is the object of preservation simply to arrest decay, or is it to educate the public? Could it, instead, be to capture the spirit of the place, while working to articulate its relevance for a modern age? Is it more a matter of land use planning and design, to revamp yesterday’s territory in a tasteful way to accommodate today’s pressing needs? SSSM, from its founding, pursued idiosyncratic answers to these questions about preservation.

Not “Living History,” but a Living Neighborhood

SSSM is currently celebrating its 50th anniversary. The intellectual context for the whole project came from the fight in the 1960s between New York developers and their outspoken critics such as Jane Jacobs and Ada Louise Huxtable.[7] One early supporter hoped that the SSSM would “weave back into the fabric of New York’s life some of the warmth and accessibility that have been lost over the years.”[8] Others suggested that the Seaport would work best if “broken into manageable bits that can be encountered and entered into casually” and advocated for a “museum without walls.”[9]

SSSM’s founders articulated a set of goals that would appear contradictory to most people. They believed that museums were ultra-conservative, irrelevant relics—with historical museums among the very worst offenders—yet they chose to anchor their project with a new museum.[10] They had nothing but contempt for what they considered theme-park-like “living history” hamlets such as Colonial Williamsburg and Mystic Seaport with candle-making demonstrations and Ye Olde Taverns, yet the whole premise of their endeavor was to preserve a neighborhood cherished precisely because of the obsolete activities that had once taken place on the waterfront.[11]

On top of this, SSSM’s founders had a low opinion of heavily reconstructed “historic” structures and artificially homogenized “period” streets. Instead, they sought to embrace the eclectic architecture and changing character of the area. This was laudable from one perspective, but it also undermined the rationale for an ambitious preservation project from the very outset. How much remained on site to preserve? If SSSM was so ambivalent about the whole discourse of heritage, did they really seek to “preserve” anything?

Inside the museum, interpretive signage invites visitors to reflect on the complexity of “preserving” a historic neighborhood in a living city

To all these quandaries, SSSM offered the somewhat oblique answer that “this museum is people.[12]” (And elsewhere: “The museum is the volunteers.”)[13] This approach to a living, dynamic neighborhood perhaps foreshadowed language about stakeholders, bottom-up organizing, and public history that would become more familiar toward the end of the twentieth century. The intention was to engage fully and honestly, in partnership with what was actually there.

What sort of people had moved in, though, when sailortown moved out? Some observers saw little more than a “ghost town.”[14] A taxi driver remarked to one early supporter, “Lady, you really shouldn’t be down in a place like this at night.”[15] Many visitors to the neighborhood in the 1960s, 70s, and 80s remarked on the pervasive stench from the fish market, the rats that swarmed to pick over the fish market’s refuse, and the feral cats who congregated to keep the rats in check. It was the sort of neighborhood where you could eat at diners unironically named Sloppy Louie’s. There was a vigorous mafia presence at Fulton Fish Market, where stalls that did not pay protection money found themselves flattened to matchsticks by gleeful truck drivers.[16] SSSM had to co-exist enough with the local mafia that when mob-fighting prosecutor Rudy Giuliani eventually became Mayor, he was hostile to a museum that he saw as tainted. Meanwhile, in the half-furnished lofts near the Fish Market dwelt squatters and counter-culture types who could no longer afford the rising rents in Greenwich Village. The list of loft residents reads like a who’s who of avant-garde American painting in the mid-twentieth century, including Jasper Johns and Robert Rauschenberg.[17]

Lindgren didn’t go to the trouble to introduce this cast of characters just for the sake of adding color. The diversity and the awkward moments neatly illustrate the ecumenical appeal of the site. What else could unite William F. Buckley, Jr., Ted Kennedy, socialites like Roberta Brooke Astor, folk singer Gordon Bok, and radical historian Jesse Lemisch?[18] The board of directors grew “heavy with yachtsmen and suburbanites,” yet South Street’s proximity to the Greenwich Village folk scene may partly explain the ready supply of singers, including Pete Seeger and Burl Ives, to perform on the pier for festivals.[19] Beat poet Allen Ginsberg did a poetry reading on Pier 16.[20] The heavy emphasis on overhauling historic sailing ships drew a few surviving old salts and the sort of Captains Courageous enthusiasts who spoke without irony about using sea training to stiffen the manly fiber.[21] This nostalgic thrust fell into alignment, however weirdly, with the seething urban discontent of the era: Several ambitious programs sought to rehabilitate drug addicts and ex-convicts using the old ships as workshops for instruction in practical trades.[22] Lindgren describes a fund-raising reception aboard the Ambrose that left the anxiety-prone David Rockefeller verging on a panic attack as he looked around the room and recognized no one from his social circle. No wonder.

As in Mad Men, this mix of the blue bloods and unregenerate old Guard with fresh springs of unruly new growth is rich in non sequiturs and comedy of manners. One of my favorites was when a volunteer worker in his tarry undershirt tried to gain entrance to a black tie gala reception to benefit the museum. The fact that, as a reader, I kept daydreaming about writing a pitch for Netflix’s next must-watch binge show is a remarkable achievement for Lindgren’s academic monograph, which is essentially about leases, zoning, and committee meetings.

Some of these diverse visions expressed themselves in a bewildering array of programming and uses for the site. Despite the initial repudiation of quaint and artisanal forms of heritage, SSSM’s “period” printing shop was used as the backdrop for a costume drama about Walt Whitman that aired on CBS in 1976.[23] Another event involved hundreds of schoolchildren expressing their identity as “newly adopted sailors” by intoning John Masefield poems and Gilbert and Sullivan lyrics.[24] Incongruously, SSSM also put on an exhibit about “American Tattoo Practice and Art” and invited the Hell’s Angels.[25]

The Politics of Preservation

In many countries, a project on the scale of South Street Seaport and its Museum could never have happened without initiation and direction from the highest levels. Instead, from the outset it was an open question whether this should be a local project run in cooperation with City Hall, or the maritime museum of the State of New York (endorsed, funded, and authorized by the legislature in Albany) or even a federal site approved by the U.S. Congress. [26]

International readers who have wondered why the United States lacks a single, imposing National Maritime Museum—such as the UK’s at Greenwich—will find some interesting context in Lindgren’s book.[27] Rivalries among many potential sites worked against that possibility. Would that national museum have been in San Francisco, at Mystic Seaport in Connecticut, or at South Street Seaport? Which influential Senators or other political figures would step forward to lobby for, or against, a particular location when the prospect came up for debate?

In the absence of support from Washington DC, the decentralized, fragmented nature of likely funding sources complicated the picture for South Street Seaport. Municipal governance in the United States, particularly in the case of big cities, tends to be an awkward and sometimes adversarial enterprise shared between local authorities, power brokers at the state level, and regulations or mandates emanating from the federal government. An early proposal to take the state funding route foundered when the Governor of New York, Nelson Rockefeller, blocked the legislation because his brother David—a developer—had other plans for the site at the time.

Ultimately, SSSM would emerge as a private-public partnership with no infusion of funds from the state or federal level. The idea of relying on philanthropic fund-raising and entrepreneurs to revitalize a derelict urban area, of course, jibed well with the increasing interest in “enterprise zones” in the Reagan era and afterwards. However, it left preservationists, for-profit developers, and the City of New York bound together by a series of lease agreements so long and complicated that even lawyers with real estate expertise reported that the wording mystified them.

Lindgren remarks in his Conclusion: “Incredibly, the Seaport was the first museum in the nation designated to undertake a major urban renewal project.”[28] In the absence of major government funding, part of the price of keeping the heritage industry at bay, and averting a future as an immaculate fossil, was to preserve the neighborhood as the pawn of developers, or more precisely, to keep out the worst kind of developers by inviting in a somewhat more benign breed. Having committed to a guiding philosophy that embraced urban change and eclecticism, South Street Seaport deprived itself of a compelling rationale to reject creeping gentrification.

Visiting the Museum: December 2017

Trinity Place Restaurant and Bar is inside a cavernous old bank vault built a century ago to withstand anarchist bomb-throwers and revolutionary mobs. It’s a little tricky to find, but well worth the trouble

I walked to South Street from the 9/11 Memorial Site, on the other side of the island, but the southern tip of Manhattan tapers to a pretty compact area. My meandering path took me through and around Wall Street, where I had lunch at Trinity Place.

The proximity to Wall Street underscores how South Street Seaport has survived against the odds. South Street was actually the original intended site for the World Trade Center, which was only relocated to its present location facing the New Jersey shore at the behest of that state’s governor. As recently as 1985, the young Donald Trump proposed to flatten the entire neighborhood and put up the world’s tallest building.[29]

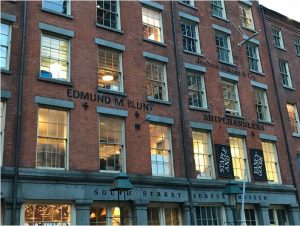

Arriving at South Street and looking around, my first impression was a twinge of excitement that I felt closer to Herman Melville’s Manhattan than I’d ever been before. Maybe I am one of those bad people who craves the illusion of a pristine “time capsule.” This photo essay from 2012 helpfully captures the aspects of the neighborhood that caught the eye of preservationists, and includes a number of important sites, such as Peck Slip, that I did not photograph.

Next to the museum’s front door, an unrelated modern storefront interrupts the brickwork and jostles for attention. The view here is facing toward the East River and Brooklyn

It is perhaps a natural, if unintended, outcome of the founders’ vision that many visitors over the decades have reported difficulty in finding the museum at all.

No sooner than I had entered the (not especially obvious) front door of the museum and paid my admission, than I was firmly escorted right back out to the street and over to the pier to board the historic ships. This, I was told, is what almost everybody comes to the museum for.

Once again, the imprint of early decisions (and preoccupations) continues to shape how SSSM is experienced today. Undeniably, several of SSSM’s vessels—such as Ambrose and Wavertree—have been museum ships for so long that they have emerged as landmarks and historic urban sites in their own right.

I came hoping for a bit more insight into the people, occupations, and stories of the waterfront. Labor historian Joe Doyle conducted in-depth interviews and oral histories of “Seaport People,” not discriminating between old salts, stewards, waitstaff, and provision-sellers.[30] In fairness, a large part of the museum remains closed after water damage from Superstorm Sandy in 2012, which briefly inundated the entire area. They did have a very interesting special exhibit called Millions. This witty title captures the incongruity between the 13 million immigrants who arrived Third Class in the years between 1900 and 1914, and the smaller number of millionaires who sailed in First Class, making the obligatory pilgrimage to Europe for high culture and fashion. The SSSM’s exhibit highlights the fact that these utterly divergent passengers sailed on the same ocean liners, and explores the circumstances of their loading and departures, where they lived on board ship, what they ate, and so forth. This is particularly appropriate for a museum situated a stone’s throw from where these passengers would have embarked or disembarked.

Here, historic buildings are reused to house Bowne Printers and a related gift shop, while the façade continues to advertise an earlier business on the premises

At Bowne Printers, I bought a hand-made artisanal postcard inscribed in blue lettering South Street Seaport: NYC’s WICKEDEST WARD with picture of a gigantic orange rat looming in the background. I didn’t fully appreciate all the resonances of this design until I read Lindgren’s book. From the trendy orange-and-blue color scheme to the sly reference to the (now-sanitized) filth and stench as well as the (now-expunged) “wicked” history of the area, this little postcard encapsulates the still-unresolved contradictions of South Street Seaport, the tension between boats and boutiques, preservation and development, not to mention the final irony of building a gift shop at the site of a bygone slum.

Notes

[1] See, for example, Edwin G. Burrows and Mike Wallace, Gotham: A History of New York City to 1898 (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1999), 649-654. For some memorable statistics on the scale and stature of New York City as the dominant North American port as late as 1945 and a quick sketch of its decline, see Benjamin W. Labaree et al., America and the Sea: A Maritime History (Mystic, CT: Mystic Seaport, 1998), 602-606.

[2] New York: New York University Press, 2014. Hereafter: Lindgren.

[3] https://parks.ny.gov/parks/155/details.aspx , accessed March 13, 2018.

[4] Johnathan Thayer, “Merchant Seamen, Sailortowns, and the Philanthropic Encounter in New York, 1843-1945,” in David Worthington, ed., The New Coastal History: Cultural and Environmental Perspectives from Scotland and Beyond (London: Palgrave Macmillan, 2017), 67-85, quoted page 77.

[5] Purists may object that Manhattan is also an island.

[6] Follower counts for @StatueEllisNPS and @SeaportMuseum compared on March 13, 2018.

[7] Lindgren, 11-16.

[8] Lindgren, 43.

[9] Lindgren, 101.

[10] Lindgren, 18, 22.

[11] Lindgren, 42.

[12] Lindgren, 288.

[13] Lindgren, 29.

[14] Lindgren, 29.

[15] Lindgren, 31.

[16] Lindgren, 103.

[17] Lindgren, 13.

[18] Lindgren, 33, 84, 110-111.

[19] Lindgren, 83-85, 116.

[20] Lindgren, 79.

[21] Lindgren, 61-62, 89-90.

[22] Lindgren, 93-95.

[23] Lindgren, 106.

[24] Lindgren, 227.

[25] Lindgren, 221.

[26] Lindgren, 17.

[27] Lindgren, 222-224.

[28] Lindgren, 288.

[29] Lindgren, 176.

[30] Lindgren, 231.

Comments are closed.