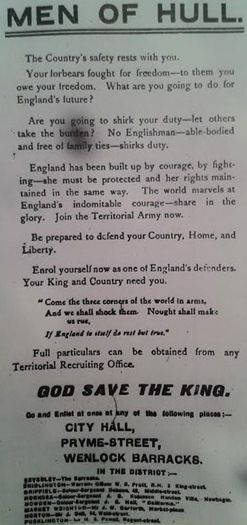

An advertisement featured in the Eastern Morning News, 25 May 1915.

Image used by kind permission of Hull History Centre

The city of Hull, East Yorkshire enjoyed the status of ‘third port’ with a booming, world-renowned fishing industry on the outbreak of war on 4 August 1914. This industry, employing many thousands of local men and women in trawling and peripheral works, was fundamentally altered by ‘total war’, as civilian fishing vessels and their men were drafted into the war effort at sea. By the end of hostilities, more than 3,000 trawlers had been co-opted for work as minesweepers along the considerable coastline of North East England.[1] This was not the only mass mobilisation on the home front in Hull. Many hundreds of women and non-combatant men contributed to the war effort by rallying support for the troops on the front, raising money for those injured and providing support those home on leave. All of this was done with a firm sense of place in mind, with Hull remaining a potent symbol for military recruiters and servicemen alike.

The distance that is often assumed to have existed between soldiers and home front workers did not materialise in Hull. Indeed, the city acted as a cultural cypher for the articulation of war experience, even working through intimate and personal testimony and correspondence. As “[windows] on a wider world”, ports like Hull hold a unique status in comparison with inland areas, acting as a ‘spatial, economic and political matrix’ in which diverse and often specialised communities can develop.[2] Within this context, a specific Hull place identity was reinforced during the war. This outlined the limits of ‘community’, producing the cultural and symbolic means for local people to “[refer] to their world”.[3] The disruption of war forced Hullensians to reassess their sense of place and, in many cases, this strengthened feelings of community within the city and across geographic space.

Many soldiers and sailors maintained strong connections with their home city, and the home front, while on active service, writing letters to loved ones and to local newspapers about their experiences. In some cases, place identity acted as a means for articulating the war experience, one of several pieces of “mental furniture” used to make sense of it.[4] Private L.W. Gamble of the 4th East Yorkshires, in a series of letters to his mother, saw Le Havre, France in terms defined by his place identity as a Hullensian: “The ships in the dock are the biggest I have ever seen. They would make two or three of the ones in Alexandra Dock”.[5] Even the cobbled streets reminded him of “our Stoneferry” (a suburb in the east of the city).[6] We can see here that the distance between the home and fighting fronts was not as wide as many historians have previously argued. Indeed, despite the physical distance standing between soldiers like Gamble and his home, the harrowing and horrific experience of the trenches was often understood in terms that they and their familial correspondents could relate to: pre-war experience of life in Hull, its streets and docks. Servicemen were still privy to elements of gossip among their family and friends, from whom their younger siblings were ‘courting’ to jokes about brothers not yet on the front line. Therefore, intimate connections were maintained and even augmented between fronts during the war, leading to what Monger terms the “concrescent community”: a “community growing closer through shared wartime experience and sacrifice, linking people within and across local and national communities”.[7] The maintenance of such intimate relations spurred on civilian mobilisation, as non-combatants could feel included in the stresses and strains of the wider war effort.[8] So there was not a complete disjuncture between wartime and pre-war civilian life. This clearly contrasts with the once prevalent views of Eric Leed and Paul Fussell on the fundamentally “liminal man” in the figure of the soldier, alienated from his friends and family back home who could not possibly contemplate the horrors of the trenches.[9] Local affiliation was also used to encourage military enlistment (see Image), identifying the “destiny of the nation” with the defence and eventual triumph of the locale.[10] A published letter by a Hull soldier makes a cheeky reference to Hull’s maritime heritage in an attempt to drum up recruits: “Roll up, bhoys, and think of your own townies… Come and avenge some of our poor comrades who have fallen amidst all the glory”(my emphasis).[11] We can see, then, the operation of a uniquely Hullensian, maritime place identity in the efforts to mobilise fighting men. But this process of mass mobilisation was intrinsically interconnected with that of home front volunteerism.

As Monger’s ‘concrescent community’ concept demonstrates, links between wartime workers and fighters of all stripes could be maintained amid the anxiety and uncertainty of war, usually resting upon well-worn aspects of local place identity. Links of solidarity and mutual support could also be fostered internationally. In Hull, this was achieved through a focus on the shared maritime heritage, culture and networks of the city and its European and Baltic counterparts. Fundraising events such as ‘flag days’ – where miniature flags were sold in return for donations for the front – were held in Hull during May and June 1915 on behalf of both Russia and France. ‘Russian Flag Day’ was made possible through relations of trade and migration, as the local press attested: “As was to be expected Hull, which has so many commercial ties with Russia, is taking up the celebration of Russian Flag Day with great enthusiasm”.[12] Remarkably, this enthusiasm included flying the Russian flag from the Guildhall and other civic buildings. A similar day held on behalf of France saw, alongside the sale of miniature Tricolours, the passage of a car through the city centre adorned with the same flag and baskets appended for the donations of pedestrians.[13]

We see a snapshot here of the operation of a specific place identity in Hull during the First World War, defined by its specific qualities as a place, geographically, socially and culturally. This was not only expressed through communications between the home and battle fronts, but acted as a readily-accessible means to understand the physical and mental displacement of industrialised war. But more than this, Hull’s maritime heritage of fishing, whaling and seafaring gave it, and its people, a fundamentally urban port identity, with strong connections with other ports many miles away. In this sense, we can say that the collective maritime identity of people in Hull, as an important port city during the First World War, not only brought local people together but transcended physical space, encouraging the mobilisation of civilians to the cause of national (though more accurately local) defence.[14]

Notes

[1] Robb Robinson, Trawling: The Rise and Fall of the British Trawl Fishery (Exeter: University of Exeter Press, 1996), 134.

[2] Brian Hoyle, “Fields of Tension: Development Dynamics at the Port-city Interface,” in ed. David Cesarani, Port Jews: Jewish communities in cosmopolitan maritime trading centres, 1550-1950, (London: Frank Cass, 2002), 14.

[3] Robert Colls, “When we lived in communities: working-class culture and its critics,” in eds. Robert Colls and Richard Rodger, Cities of Ideas: civil society and urban governance in Britain, 1800-2000, (Aldershot: Ashgate, 2004), 298.

[4] Jay Winter and Antoine Prost, The Great War in History: debates and controversies, 1914 to the present (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2005), 164.

[5] Transcripts of letters by Pte. L.W. Gamble, c.August 1915, LIDDLE/WWI/GS/0603A, Liddle Collection, Special Collections, University of Leeds.

[6] Transcripts of letters by Pte. L.W. Gamble, c.August 1915, LIDDLE/WWI/GS/0603A, 4 December 1915.

[7] David Monger, “Soldiers, Propaganda and Ideas of Home in First World War Britain,” Cultural and Social History, vol. 8, no. 3, (2011), 332; Peter Grant, Philanthropy and Voluntary Action in the First World War: Mobilizing Charity (New York: Routledge, 2014), 174.

[8] Michael Roper, The Secret Battle: emotional survival in the Great War (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2009), 50.

[9] Eric Leed, No Man’s Land: Combat & Identity in World War I (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1981), 2; David Englander, “Soldiering and Identity: Reflections of the Great War,” War in History, vol. 1 no. 3, (1994), 316.

[10] John Horne and Alan Kramer, German Atrocities, 1914: A History of Denial (London: Yale University Press, 2001), 307.

[11] Hull Times, 14 August 1915, 6.

[12] Hull Daily News, 11 May 1915, 1.

[13] Hull Times, 17 July 1915, 4.

[14] Pierre Purseigle, “Wither the Local? Nationalisation, Modernisation, and the Mobilisation of Urban Communities in England and France, c.1900-18,” in eds. William Whyte and Oliver Zimmer, Nationalism and the Reshaping of Urban Communities in Europe, 1848-1914, (Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2011), 194.

Bibliography

Primary sources

Liddle Collection, Special Collections, University of Leeds

LIDDLE/WWI/GS/0603A: Transcripts of letters by Pte. L.W. Gamble, c.August 1915.

Hull History Centre

Hull Daily News, 11 May 1915.

Hull Times, 17 July 1915.

Hull Times, 14 August 1915.

Secondary sources

Colls, Robert, “When we lived in communities: working-class culture and its critics,” in eds. Robert Colls and Richard Rodger, Cities of Ideas: civil society and urban governance in Britain, 1800-2000, (Aldershot: Ashgate, 2004), 283-307.

Englander, David, “Soldiering and Identity: Reflections of the Great War,” War in History, vol. 1, no. 3, (1994), 300-318.

Grant, Peter, Philanthropy and Voluntary Action in the First World War: Mobilizing Charity (New York: Routledge, 2014).

Horne, John and Alan Kramer, German Atrocities, 1914: A History of Denial (London: Yale University Press, 2001).

Hoyle, Brian, “Fields of Tension: Development Dynamics at the Port-city Interface,” ed. David Cesarani, Port Jews: Jewish communities in cosmopolitan maritime trading centres, 1550-1950, (London: Frank Cass, 2002), 12-30.

Leed, Eric, No Man’s Land: Combat & Identity in World War I (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1981).

Monger, David, “Soldiers, Propaganda and Ideas of Home in First World War Britain,” Cultural and Social History, vol. 8, no. 3, (2011), 331-354.

Purseigle, Pierre, “Wither the Local? Nationalisation, Modernisation, and the Mobilisation of Urban Communities in England and France, c.1900-18,” in eds. William Whyte and Oliver Zimmer, Nationalism and the Reshaping of Urban Communities in Europe, 1848-1914, (Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2011), 95-124.

Robinson, Robb, Trawling: The Rise and Fall of the British Trawl Fishery (Exeter: University of Exeter Press, 1996).

Roper, Michael, The Secret Battle: emotional survival in the Great War (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2009).

Winter, Jay and Prost, Antoine, The Great War in History: debates and controversies, 1914 to the present (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2005).

Comments are closed.