Such was the infamy of the English prison hulks that Napoleon Bonaparte is reported to have shouted before the battle of Waterloo: “Soldiers, let those among you who have been prisoners of the English describe to you the hulks, and detail the most frightful miseries which they endured!”[1] It is interesting that Napoleon, the person declaiming about the horrid nature of English prison ships, was one of the men principally responsible for their extended use and development. As historian Gavin Daly notes, it was whilst under the French Emperor’s reign during the Napoleonic Wars (1803-14) that the “traditional” treatment of prisoners of war (involving cartel ships and parole) went by the wayside.[2] The French Revolution dismantled societal norms of culture and class—and certainly changed the entrenched gentlemen culture of advancement that existed within the military. However, it was Napoleon who refused to send English prisoners of war home, and it was Napoleon who decided that he would force England to bear the brunt of upkeep for the 102,000 French prisoners who were captured by the English.

Such was the infamy of the English prison hulks that Napoleon Bonaparte is reported to have shouted before the battle of Waterloo: “Soldiers, let those among you who have been prisoners of the English describe to you the hulks, and detail the most frightful miseries which they endured!”[1] It is interesting that Napoleon, the person declaiming about the horrid nature of English prison ships, was one of the men principally responsible for their extended use and development. As historian Gavin Daly notes, it was whilst under the French Emperor’s reign during the Napoleonic Wars (1803-14) that the “traditional” treatment of prisoners of war (involving cartel ships and parole) went by the wayside.[2] The French Revolution dismantled societal norms of culture and class—and certainly changed the entrenched gentlemen culture of advancement that existed within the military. However, it was Napoleon who refused to send English prisoners of war home, and it was Napoleon who decided that he would force England to bear the brunt of upkeep for the 102,000 French prisoners who were captured by the English.

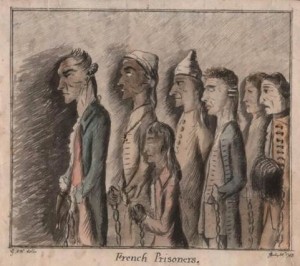

An unintended consequence of Napoleon’s decision to leave his men stranded on enemy soil, and subsequently forcing them to live in abysmal conditions inside hulks scattered along the coasts of Portsmouth, Plymouth and Chatham,[3] was that he unwittingly set the stage for the development of a new kind of prisoner of war—the prisoner of war as renegade captive, desperate to be free.

The prison hulks were initially supposed to be a temporary solution to a very volatile problem. In 1775, England’s prisons were overflowing because convicts could no longer be shipped to Maryland and Virginia because of war with the colonies.[4] By the 1780s, convicts would begin their long journey to Botany Bay.[5] However, even with ship after ship of convicts being sent to Australia, the prison hulks remained. Not only that, their population expanded to include prisoners of war. Lack of food, constant overcrowding, the brutality of the guards, exposure to disease, meant that the French suffered greatly under the hands of the English. “Imagine a generation of the dead coming forth from their graves…and still you have no more than a feeble…idea of how my companions in misfortune appeared,” Louis Garneray wrote in The Floating Prison which chronicled his nine years of captivity inside Portsmouth’s prison hulks.[6]

Perhaps it is no surprise that as soon as the prisoners were captured, many planned their escape. That said, what happened on the Prince cartel back in 1802 seems a tale more out of a Patrick O’Brien novel rather than a true story of war. According to The Times, [7] French prisoners of war kept inside the Prince and on course for England (and the dreaded prison hulks), used billets of firewood as weapons and seized the ship from their English captors. The Prince was sailing with the 74 gun Suffolk, and the French captives, having stolen the Prince’s signal book, followed the Suffolk’s signals as if all was well. One can only imagine what was going on in the minds of the men as they sailed alongside the large (and heavily armed) Suffolk for two days—just waiting for right time to make their move. On the third day, according to The Times, they got their chance. A squall came in and the men used the rain and thunder as their shield and sailed away to freedom.

Perhaps it is no surprise that as soon as the prisoners were captured, many planned their escape. That said, what happened on the Prince cartel back in 1802 seems a tale more out of a Patrick O’Brien novel rather than a true story of war. According to The Times, [7] French prisoners of war kept inside the Prince and on course for England (and the dreaded prison hulks), used billets of firewood as weapons and seized the ship from their English captors. The Prince was sailing with the 74 gun Suffolk, and the French captives, having stolen the Prince’s signal book, followed the Suffolk’s signals as if all was well. One can only imagine what was going on in the minds of the men as they sailed alongside the large (and heavily armed) Suffolk for two days—just waiting for right time to make their move. On the third day, according to The Times, they got their chance. A squall came in and the men used the rain and thunder as their shield and sailed away to freedom.

It is interesting that no English soldiers or officers seem to have been injured during their escape. In fact, according to The Times, the French prisoners of war sailed the Prince into the Mauritius and the former French prisoners boarded the 36 gun Bellona privateer. Thus, it seems the French left the English captors on the Prince unmolested. Perhaps they were still not able to let go entirely of the pre-French Revolutionary gentlemen culture of the military.

Historians studying the English prison hulks are inundated with stories of unmitigated suffering and human dissipation. Over 12,000 Frenchmen died in English prisons during the Napoleonic Wars and over 70,000 who returned after 1814 came back with serious health issues.[8] No doubt, that is what makes the little known story of this group of French prisoners of war and their bold escape on the Prince all the more remarkable.

Notes

[1] Paul Chamberlain, Hell Upon Water: Prisoners of War in Britain, 1793-1815, (Gloucestershire: The History Press, 2008) 76.

[2] Gavin Daly, “Napoleon’s Lost Legions: French Prisoners of War in Britain, 1803-1814,” History vol. 89, no. 295 (2004): 361.

[3] Clive L. Lloyd, A History of Napoleonic and American Prisoners of War 1756-1816, (Suffolk: Antique Collector’s Club, 2007), 81.

[4] Charles Campbell, The Intolerable Hulks: British Shipboard Confinement 1776-1857 (Maryland: Heritage Books, 1994), 10.

[5] Edward Marston, Prison: Five Hundred Years of Life Behind Bars, (Surrey: The National Archives. 2009) 80.

[6] Louis Garneray, The Floating Prison: The Remarkable Account of Nine Years’ Captivity on the British Prison Hulks During the Napoleonic Wars, trans. Richard Rose (London: Conway Maritime Press, 2003) , 5.

[7] The Times, August 23, (1802), issue 5490, page 3.

[8] Lloyd, A History of Napoleonic and American Prisoners of War, 97.

Lovely article, Carolyn. I’m working on new interpretation at Edinburgh Castle’s prisons of war – some engaging tales of American prisoners there. I wondered whether you could let me know where you found the top picture of French prisoners? I’d like to track it down to get a high-res version and licence.