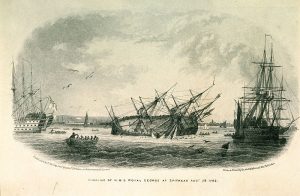

On August 29th 1782, the 100-gun warship HMS Royal George sunk whilst lying at anchor off Spithead. The death toll was huge, with estimates varying between six hundred and one thousand people drowned. Most accounts of the sinking have sought to explain why the ship sank and who was to blame, but by placing the attribution of blame to one side, this tragic event can be viewed in the context of its appearance in various forms of British naval culture in subsequent years. This article focuses on the different ways in which the wreck has been represented and accommodated into cultural forms, including national memorials and consumable material culture.

On August 29th 1782, the 100-gun warship HMS Royal George sunk whilst lying at anchor off Spithead. The death toll was huge, with estimates varying between six hundred and one thousand people drowned. Most accounts of the sinking have sought to explain why the ship sank and who was to blame, but by placing the attribution of blame to one side, this tragic event can be viewed in the context of its appearance in various forms of British naval culture in subsequent years. This article focuses on the different ways in which the wreck has been represented and accommodated into cultural forms, including national memorials and consumable material culture.

In 1782 the Royal George was an old ship, having been built in 1755, but as a rebuild of the older vessel Royal Anne. She had served with distinction in both the Seven Years War and the American Revolutionary War.[1] In August 1782, with Rear-Admiral Richard Kempenfelt on board, she was being hastily refitted at Spithead before sailing with Admiral Howe’s fleet to relieve Gibraltar, and it was deemed necessary that she be heeled over for maintenance to be carried out on a normally submerged cistern pipe. This involved running some of the guns and provisions over to one side of the ship, causing the other side to rise out of the water. However, the ship’s carpenter soon reported that she was taking on water through her ports. Despite the captain attempting to correct the heel, the ship quickly sank, taking a victualing cutter that had unfortunately moored alongside with her. Most accounts agree that upwards of six hundred people were drowned, and Rear-Admiral Kempenfelt was amongst them, after the doors of his cabin were forced shut by the weight of the on-rushing water.[2]

The immediate after effects of the sinking on the surrounding coastline were shocking and highly visible to contemporary observers. John Ker, a surgeon on board the Queen wrote,

every hour corpses were coming ashore on the beach, every hour the bell was tolling and the long procession winding along the streets.[3]

The death toll was massively increased by the number of non-naval personnel on board; many of the crewmember’s wives were present, as commonly occurred before a warship set sail. Ker also noted that the whole area “was in a commotion”, with every person in Portsmouth and Gosport having lost someone who was known to them in some capacity.

The resulting court martial divested blame from the senior officers, and instead asserted that the age of the ship’s timbers had caused part of her frame to give way because of the force of the heel.[4] This has been described by one modern commentator as a “whitewashing verdict”,[5] and there remains a suspicion that the Admiralty were seeking to suppress suspicion that their own failure to correctly repair the vessel had caused the wreck. Whatever the cause, the significance of the vessel’s loss in subsequent British naval and national culture has been severely overlooked. During the naval mutinies of 1797, a satirical writer attempted to invoke ‘the spirit of Kempenfelt’, the Rear-Admiral who drowned with the ship, in order to secure a settlement between the authorities and the mutineers.[6] The spatial connection between the wreck and the mutiny, both occurring at Spithead, was obvious to many sailors because up until 1794 the sunken Royal George’s masts were still visible above the waterline at low tide.[7] Kempenfelt was also memorialised in William Cowper’s poem On The Loss of the Royal George, which included the lines:

Weigh the vessel up,

Once dreaded by our foes,

And mingle with your cup

The tears that England owes [8]

The poem stressed the benign circumstances in which the ship had been lost: “It was not in the battle; No tempest gave the shock”, and that when Kempenfelt died “His sword was in its sheath.” This sentiment chimed with the feelings of the deceased crewmember’s families, who struggled to reconcile the expectations of glory placed upon British sailors with the fact that their relatives had not died in battle.[9] Various attempts to salvage the vessel were proposed, extending into the 1840’s, and were accompanied by the latest developments in diving technology, including a new ‘closed’ suit.[10] These diving operations were used as the setting for a macabre short story entitled ‘A Night in the Royal George’ (1834), in which an intrepid individual with hopes of making his fortune resolves to undertake a lone night-time dive into the wreck. Whilst there he encounters:

a dreadful corpse, that gibbered and grinned directly in my face: it was the body of some creature, who had perhaps been forced in there at the first rush of the water; and the door closing in upon him, had kept out the sand and marine insects that everywhere else abounded.[11]

Although this is clearly a reference to Kempenfelt, the significance of the wreck within national memory ensured that naming him was not necessary, as anyone familiar with the story would have immediately recognised the author’s intention. Rather than being reserved simply for displays of grief in a proud national setting, the Royal George and the spectral body (as well as the ‘spirit’) of Kempenfelt were subsumed into the constantly evolving and highly imaginative forms of literary culture.

Eventually the wreck was blown up, but not before most of her cannon and some of her timbers had been salvaged, and they soon found their way into various forms of national memorial. Some of her cannons were melted down to form the base of Nelson’s column at Trafalgar Square.[12] The ship’s bell was recovered and displayed at the Dockyard Chapel in Portsmouth,[13] and a capstan was sent to Plymouth,[14] ensuring that the Royal George’s memory retained a presence in Britain’s two foremost naval towns. One item did find its way to a more provincial location, with a cannon being recast as the lantern for a new lighthouse on the river Dee.[15] But relics from the ship also became appropriated into material culture, and their popularity stretched across the social classes. In all of their various forms there was one connecting theme: like the commemorations discussed above, the physical embodiment of the ship was utilised, but instead it was used to create a consumable reproduction. A Portsmouth publisher printed two thousand small books that contained eyewitness accounts of the sinking, all of which were bound in wood recovered from the wreck.[16] William Wordsworth owned a box and a walking stick made out of the ship’s timbers, as revealed in a letter of 1848.[17] Miniature cannons, commemorative coins and snuffboxes were also made out of the recovered materials, and such materials were described in 1875 as “treasured by our seafaring nation”.[18]

Gregson, Crang and Watkins have argued that manufactured souvenirs resulting from the “death” of a ship can serve to “reanimate” a geographically dispersed set of survivors.[19] In this case, the ‘reanimation’ took place on a national scale; the loss of Royal George had been a British national trauma, and thus the engagement with the material souvenirs was not confined to a small group of survivors. The authenticity of these souvenirs notwithstanding, they retained their significance by conceptually connecting people to the traumatic event long after it had occurred. In the early twentieth century, when the formation of a National Naval and Maritime Museum was proposed, minutes from a 1926 meeting of the Society for Nautical Research suggested that “the authentic relics of the Royal George” should be included, along with Sir Francis Drake’s Drum, Robert Blake’s flag and the coat worn by Nelson at Trafalgar.[20] To be placed alongside items so greatly treasured in British naval culture indicated that the memory of the wreck still resonated greatly in the national consciousness. The very name of the ship became a byword for deterioration; the speaker of the Society for Nautical Research’s annual lecture in 1935 alluded to John Harrison’s No. 1 chronometer as “looking as though it had gone down with the Royal George and been on the bottom ever since”.[21]

Although the Royal George has receded from national memory in recent years, the tragedy was for a long time front and centre in representations of British naval culture. The survival of HMS Victory, a contemporary of the Royal George, serves as a living reminder of the longevity of British naval power. Yet the loss of the Royal George did not prevent it from having a similar place in discussions of Britain’s naval heritage. Its importance continues to this day, with relics from the wreck still regularly sold on online auction sites. Timothy Jenks argues that the Georgian navy was represented in ways that were “substantial, diverse, and expressed in a range of cultural forms”,[22] and this is shown in the various forms of literary and material culture that the vessel’s memory and relics became appropriated into. Representations of the navy in popular culture were not simply limited to portraying success in battle, as this wreck which occurred in home waters testifies. The Royal George took on another life after slipping beneath the waves, in which it became both physically and conceptually integral in constructions of national identity.

Notes

[1] Rif Winfield, British Warships in the Age of Sail 1714 – 1792 (Barnsley: Seaforth Publishing, 2007), 5.

[2] David Hepper, British Warship Losses in the Age of Sail 1650 – 1859 (Rotherfield: Jean Boudroit Publications, 1994), 69.

[3] “Journal of John Ker, Surgeon” National Library of Scotland MS. 1038 – quoted in: “Notes”, The Mariner’s Mirror, vol. 32, no.1 (1946): 188.

[4] Hepper, British Warship Losses, 69.

[5] David Blackmore, Blunders and Disasters at Sea (Barnsley: Pen & Sword Books, 2004), 52.

[6] David W. London, “The Spirit of Kempenfelt” in eds. Ann Veronica Coats and Phillip MacDougall, The Naval Mutinies of 1797: Unity and Perseverance (Woodbridge: The Boydell Press, 2011), 95.

[7] R. J. B. Knight, Portsmouth Dockyard Papers 1774-1783: The American War (Portsmouth: City of Portsmouth, 1987), 109.

[8] William Cowper, “On the loss of the Royal George”, in The Book of the Ocean and Life on the Sea (Auburn and Rochester: Alden & Beardsley, 1857), 148.

[9] Roald Kverndal, “The 200th Anniversary of organized Seamen’s Missions, 1779-1979”, The Mariner’s Mirror, vol. 64, no.1 (1979): 259.

[10] Graham Smith, Hampshire and Dorset Shipwrecks (Newbury: Countryside Books, 1995), 70.

[11] “A Night in the Royal George”, in The Literary World: a Journal of Popular Information and Entertainment. Saturday, June 13, 1840, 174.

[12] John Bevan, The Infernal Diver (London: Submex, 1996), 201.

[13] “Port Correspondence”, in The United Service Journal and Naval and Military Magazine, vol. 31, part 3 (London: Henry Colburn, 1839): 541.

[14] Transactions of the Historic Society of Lancashire and Cheshire, Volume 1 (Liverpool: Adam Holden, 1861), 333.

[15] Hyde Clarke, “On Lighthouses”, The Illustrated Sailor’s Magazine, and new Nautical Miscellany, Volume 1 (1845): 51.

[16] ‘A Narrative of the Loss of the Royal George at Spithead, August 1782’ (Portsea: S. Horsey)

[17] The Letters of William and Dorothy Wordsworth: Volume VIII. A supplement of new letters. Edited by Alan G. Hill (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1993), 257.

[18] “The Exhibition of Naval Models at Greenwich”, The Nautical Magazine for 1875, Volume XLIV, no.1 (1875): 666.

[19] Nicky Gregson, Mike Crang and Helen Watkins, “Souvenir salvage and the death of great naval ships”, Journal of Material Culture, vol. 16, no.3 (2011): 305.

[20] “National Naval and Nautical Museum: Annual General Meeting of the Society for Nautical Research”, The Mariner’s Mirror, vol. 13, no.1 (1927): 200-201.

[21] Rupert T. Gould, “annual lecture for 1935: John Harrison and his Time-keepers”, The Mariner’s Mirror, vol. 21, no.2 (1935): 131.

[22] Timothy Jenks, Naval Engagements: Patriotism, Cultural Politics, and the Royal Navy 1793-1815 (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2006), 7.

Comments are closed.