In 1925, J. Stanley Gardiner, a Cambridge don and fisheries expert, made a public statement of regret that the Great Barrier Reef existed. “It is the greatest pity in the world,” he told the Royal Geographical Society, “… a tragedy so far as the people of Queensland are concerned.” Gardiner explained that the reef was a navigation hazard, and worse, the coral made commercial trawling impractical. [1] Iain McCalman’s new book traces the origins of modern ecological consciousness in Australia, but also offers an unflinching look at those who remained immune to the Reef’s charms. As late as the 1960s, the Queensland government connived in plans to prospect for oil in the Reef, using drilling and seismic blasting. [2] Nearby rainforest was co-opted by the Australian military “for exercises in jungle warfare and defoliant bombing.” [3] A visiting American geologist recommended that the “non-living” parts of the Reef “should be developed as sources for agricultural fertilizer and cement manufacture.” [4] A Queensland politician, questioned about the risk of oil slicks, remarked that oil contained protein and should be a nutritious supplement for the tropical fish. [5]

In 1925, J. Stanley Gardiner, a Cambridge don and fisheries expert, made a public statement of regret that the Great Barrier Reef existed. “It is the greatest pity in the world,” he told the Royal Geographical Society, “… a tragedy so far as the people of Queensland are concerned.” Gardiner explained that the reef was a navigation hazard, and worse, the coral made commercial trawling impractical. [1] Iain McCalman’s new book traces the origins of modern ecological consciousness in Australia, but also offers an unflinching look at those who remained immune to the Reef’s charms. As late as the 1960s, the Queensland government connived in plans to prospect for oil in the Reef, using drilling and seismic blasting. [2] Nearby rainforest was co-opted by the Australian military “for exercises in jungle warfare and defoliant bombing.” [3] A visiting American geologist recommended that the “non-living” parts of the Reef “should be developed as sources for agricultural fertilizer and cement manufacture.” [4] A Queensland politician, questioned about the risk of oil slicks, remarked that oil contained protein and should be a nutritious supplement for the tropical fish. [5]

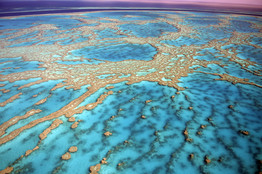

McCalman’s history of the Reef’s defenders is complex and inclusive, ranging across Aborigines, eccentrics, and beachcombers. The most insightful contributions have often come from those lacking conventional academic credentials, or from individuals whose approach to science was informed by hands-on experience and moments of poetic insight alone on the Reef. In response to the Queensland government’s development plans, an alliance of amateurs and artists proposed an alternative conception of what their country was about: “The Reef had to be something that plumbed the deepest reservoirs of Australian imagination, intuition, and knowledge; it had to be seen as more profound and urgent than any temporary accession of material wealth.” [6] The Queensland politicians lost control of the Reef, and ultimately it would be protected not just by the Australian government but by the international community, as a UNESCO World Heritage site. [7] (However, the current Australian government is not especially keen on conservation; see here and here.)

I heard McCalman give a keynote based on this project at the “Sea Stories” conference in Sydney last summer. He spoke at the Australian National Maritime Museum and led off with this short video, which had been filmed as a proof-of-concept sketch to interest TV executives who might commission a full series. After he played it, Michael Pearson (of “littoral societies” fame) turned to me and said, “This is what we should all be doing.”

At the time, I agreed. Yet I’m not sure McCalman’s approach would work equally well for any coast. What, precisely, is imitable about his video, or his book?

When I consider the average stretch of coast in the United States, for example, it isn’t a candidate for UNESCO World Heritage listing. I think of the miles of chemical vats and seething, steaming refineries in the Houston Ship Channel, an eerie mechanized vista missing only some chattering droids to win a place in a George Lucas film. As someone who grew up in Ohio, I must mention Cleveland’s Cuyahoga River, so polluted that it has set part of Lake Erie on fire several times. Even Washington State’s Puget Sound, backed by the snow-capped Olympic Mountains, is dominated by the ranks of gleaming, gigantic cranes lining the container-ship docks.

Then there is Indiana’s small and little-heralded shoreline on Lake Michigan. This area is best known for the colossal smokestacks of the old U.S. Steel plant in Gary, Indiana (plainly visible from Navy Pier in Chicago), and crumbling, predominantly African-American rust belt towns. Yet the impressive Indiana Dunes were saved by citizen agitation and preserved, mostly undeveloped, for posterity. (I say mostly undeveloped, because once you cast off your shoes and labor up the steep sandy slopes to a commanding view of steely-blue Lake Michigan, it is impossible to avoid noticing the nuclear power plant just outside the protected area.)

Part of the dilemma of environmental writing that focuses on the biggest and best, the explosive moments of scientific insight, and the planet’s most sublime treasures is that it leaves the rest of us a little unsure how to speak about our less-than-inspiring scenery and our bland or pathetic narratives. There may even be a relationship between the dissemination of what is, only half-jokingly, called “eco-porn” and a dismissive attitude toward second-best scenery. Worse still, reverence for unspoiled places may foster an impatient readiness to shrug off a coast as already too tarnished to merit conservation efforts. A hunger or itch for the sublime is one of the most powerful assets for the environmental campaigner—McCalman makes a compelling case that without such sacred causes, we might not have any protection for wilderness at all—but we will make little progress on a planetary scale until we are also willing to study, visit, cherish, write about, and campaign for our ugliest coasts.

Notes

[1] Iain McCalman, The Reef, a Passionate History: The Great Barrier Reef from Captain Cook to Climate Change (New York: Scientific American / Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2013), 212-213.

[2] McCalman, 232.

[3] McCalman, 239.

[4] McCalman, 242.

[5] McCalman, 246.

[6] McCalman, 244.

[7] McCalman, 247.

Comments are closed.