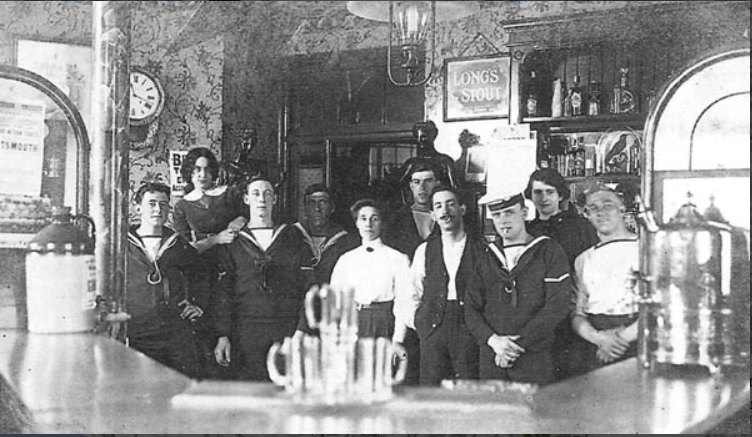

Taverns and other drinking establishments occupy a privileged place in the iconography of ports and sailortowns. Who could forget the free-and-easy multicultural egalitarianism of ALL-MAX, the East End dive immortalized by Pierce Egan? [1] In The Many-Headed Hydra, Marcus Rediker and Peter Linebaugh speculated about what sorts of conversations sailors, slaves, sex workers, and assorted renegades might have had when they crossed paths in taverns. [2] In the spirit of Bertold Brecht’s “Questions from a Worker Who Reads,” after a day’s hard work, where did the builders of the Atlantic world go? It would seem that they went to the tavern. [3]

Taverns and other drinking establishments occupy a privileged place in the iconography of ports and sailortowns. Who could forget the free-and-easy multicultural egalitarianism of ALL-MAX, the East End dive immortalized by Pierce Egan? [1] In The Many-Headed Hydra, Marcus Rediker and Peter Linebaugh speculated about what sorts of conversations sailors, slaves, sex workers, and assorted renegades might have had when they crossed paths in taverns. [2] In the spirit of Bertold Brecht’s “Questions from a Worker Who Reads,” after a day’s hard work, where did the builders of the Atlantic world go? It would seem that they went to the tavern. [3]

At a more humble level, taverns served as a sort of urban space even in corners of the Atlantic world that had not yet developed substantial towns. In “Keeping the Trade: The Persistence of Tavern keeping among Middling Women in Colonial Virginia,” Sarah Hand Meacham devotes several pages to summarizing the extraordinarily diverse functions of taverns, serving as slave markets, news emporia, and post offices but also as venues for cock fighting and the exhibition of exotic animals. [4]

Such establishments were often owned and operated by women, and even passed down routinely from mother to daughter. (As Meacham remarks, this was true even in a number of cases where the license was, nominally, held by a husband or father.) In her study of non-elite or downwardly mobile white women in the Leeward Islands, Natalie Zacek summarizes how the authorities rationalized this practice: “…the granting of a tavern license would allow the councilors of an island to portray themselves simultaneously as generous, by giving assistance to impoverished and deserving women, and as hard-headed, by offering these women an opportunity for self-help rather than outright charity.” [5] Yet the outcome of this paternalist logic was to allow women to dominate one of the most strategic locations in these communities.

While port towns have tended to offer women special leeway and unusual opportunities, the exact scope of that freedom has varied over time, and tavern keeping is no exception. In “Ports, Petticoats, and Power: Women and Work in Early-National Philadelphia,” Sheryllynne Haggerty shows how the number of women listed as proprietors of coffee houses, taverns, or inns in the Philadelphia Trade Directories fell by half between 1785 and 1805. [6] Here is Haggerty’s explanation for this trend: “In Philadelphia, as in Liverpool and Virginia, certain public functions were increasingly held at inns and taverns, including auctions and meetings regarding debtors and creditors. Even the waterfront taverns were often used by ship owners and captains to conduct business. As spaces therefore, inns, and taverns were increasingly used for business and other public roles, which made it less culturally acceptable for women to both run and work in them, especially as ideas of separate spheres took hold.” [7] She also suggests that women were gradually shamed out of management positions in taverns and coffee houses of a less savory type; the premise now was that a woman who appeared in such a space must be a “working girl.” [8]

To some extent, Haggerty and Zacek are looking at different sorts of women, and different sorts of drinking establishments. Egan’s ALL-MAX, one imagines, would never have appeared in a printed Town Directory. Still, it is hard to think about ALL-MAX in quite the same way after reading about the central and enduring role played by women in owning and operating many places like it.

Notes

[1] Pierce Egan, Life in London (1821).

[2] Marcus Rediker and Peter Linebaugh, The Many-Headed Hydra: Sailors, Slaves, Commoners, and the Hidden History of the Revolutionary Atlantic (Boston: Beacon, 2001).

[3] Brecht’s poem is invoked in Natalie Zacek, “Between Lady and Slave: White Working Women in the Eighteenth-Century Leeward Islands,” in Douglas Catterall and Jodi Campbell, eds., Women in Port: Gendering Communities, Economies, and Social Networks in Atlantic Port Cities, 1500-1800 (Leiden: Brill, 2012), 127-150, Brecht quoted on page 138.

[4] Sarah Hand Meacham, “Keeping the Trade: The Persistence of Tavernkeeping among Middling Women in Colonial Virginia,” Early American Studies: An Interdisciplinary Journal 3, no. 1 (Spring 2005), 140-163; diverse functions discussed on pages 144-149. See also Zacek, “Between Lady and Slave,” 138.

[5] Zacek, “Between Lady and Slave,” 143.

[6] Sheryllynne Haggerty, “Ports, Petticoats, and Power: Women and Work in Early-National Philadelphia,” in Douglas Catterall and Jodi Campbell, eds., Women in Port: Gendering Communities, Economies, and Social Networks in Atlantic Port Cities, 1500-1800 (Leiden: Brill, 2012), 103-126; chart on page 109.

[7] Haggerty, “Ports, Petticoats, and Power,” 120.

[8] Haggerty, “Ports, Petticoats, and Power,” 121.

Comments are closed.