Portsmouth, 21st May 1662:

Portsmouth, 21st May 1662:

“I arrived here yesterday about two in the afternoon, and as soon as I had shifted myself I went to my wife’s chamber. Her face is not so exact as to be called a beauty, though her eyes are excellent good, and not anything in her face that in the least degree can [shoque] one; on the contrary, she hath much agreeableness in her looks altogether as ever I saw; and if I have any skill in physiognomy, which I think I have, she must be as good a woman as ever was born. Her conversation, as much as I can perceive, is very good; for she has wit enough and a most agreeable voice. You would wonder to see how well we are acquainted already; in a word, I think myself very happy, for I am confident our two humours will agree very well together.”[1]

NPG D11129; King Charles II & Catherine of Braganza. Reproduced under the Creative Commons License: Copyright National Portrait Gallery

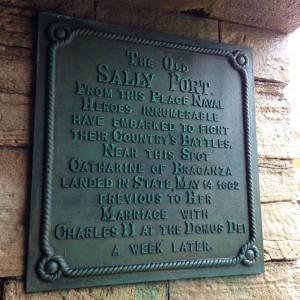

These were the first impressions King Charles II confided to Lord Clarendon following his first meeting with his wife to be, the Infanta of Portugal, Catherine Duchess of Braganza. Catherine had arrived at Portsmouth on the 14th of May 1662, where she stayed at the Governor’s House in Old Portsmouth awaiting the King. Samuel Pepys, no stranger to Portsmouth, especially in later years as Secretary to the Admiralty, recorded in his diary, “At night, all the bells of the town rung, and bonfires made for the joy of the Queen’s arrival, who came and landed at Portsmouth last night.”[2] Two of Portsmouth’s oldest buildings, the church of St Thomas Becket, which is today Portsmouth Cathedral, and the Royal Garrison Church, were witness to the events of the royal wedding which took place in Portsmouth in 1662.

With the future Queen’s arrival in Portsmouth, preparations were made for the arrival of the King and the royal wedding. There was, however, a problem. The English Civil War had left St Thomas’s Church, the parish church of Portsmouth dedicated to St Thomas Becket, heavily damaged from fighting during a short siege. In 1642, the Royalist garrison in Portsmouth had used the church tower to observe the movement of Parliamentary forces in nearby Gosport. Parliamentary gunners fired their cannons at the tower, inflicting heavy damage to the church destroying the medieval tower and much of the nave. The only suitable venue for a royal wedding, therefore, was the nearby “Domus Dei” (House of God).

The Domus Dei, originally built in 1212 by the Bishop of Winchester, had once been the old medieval hospital of Portsmouth, which fortuitously survived the Dissolution of the Monasteries in the 16th century by first becoming an armoury for the town, and later the chapel to the Governor’s House which was built adjoining the site.[3] It was here at Governor’s House that Catherine is reputed to have first introduced the custom of drinking tea in England during her time in Portsmouth, which she would continue at court throughout her life.[4]

Reproduced with permission from Portsmouth Cathedral. Copyright: John Bolt

The marriage between the newly restored King of England and the Portuguese Infanta took place in Portsmouth on the 21st of May 1662. The actual wedding service, however, is believed to have taken place in the Governor’s Presence Chamber and not the chapel itself.[5] Besides a considerable dowry of some two million Portuguese Crowns, England also gained from Portugal the North African port of Tangiers, further trading routes in the East Indies, and the ports of Bombay in present day India.

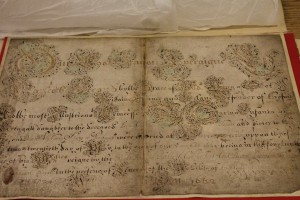

Today, St Thomas’s Church, its origins as an Augustinian Abbey dating to around 1185, is now Portsmouth Cathedral.[6] Recently as part of ongoing restoration work to the cathedral, a stone musket ball, presumably dropped by a Royalist soldier, was discovered in the tower where it can be seen in the cathedral nave today. Portsmouth Cathedral is today the custodian of the marriage certificate of King Charles II and Catherine, as well as some of the silver “Tangier Plate” taken from the garrison of Tangiers. With the restoration of Charles II, money was raised to restore the damage done to the country by the Civil War with a special collection established for the churches. This fund provided the money required to rebuild the tower and nave of St Thomas’s Church which was completed in 1693 in the new classical style which can be seen today at Portsmouth Cathedral.[7]

Copyright: John Bolt

The Domus Dei in Old Portsmouth is better known today as the Royal Garrison Church, and remained witness to other extraordinary events in Portsmouth. Government saw one of its last uses in 1814 for a meeting of the Allied Sovereigns celebrating the defeat of Napoleon[8], and one of Portsmouth’s largest public funerals for General Sir Charles Napier who is buried in the church yard.[9] Later demolished in 1826, it was this house where Catherine stayed in her first days in Portsmouth and which witnessed the marriage of the King and Queen. The Royal Garrison Church suffered considerable damage in the Portsmouth Blitz of 1941 and the roof of the nave was lost to an incendiary bomb. Today only the church remains and is preserved by English Heritage.[10]

Sadly, Catherine bore no live children although Charles acknowledged at least twelve children from his mistresses and liaisons. Charles’ brother James would succeed him to the throne.

The marriage certificate of Charles and Catherine is today held at Portsmouth Cathedral. Having recently been on display at the National Maritime Museum in Greenwich as part of an exhibition on Samuel Pepys, planning is underway to display the certificate in Portsmouth in a more permanent setting for public viewing.

John Bolt is the Marketing Coordinator for Portsmouth Cathedral and is also a Volunteer Guide at the Royal Garrison Church in Old Portsmouth.

Notes

[1] H.P. Wright, The Story of the ‘Domus Dei’ of Portsmouth, (London: James Parker & Co., 1873), 21.

[2] “Samuel Pepys’ Diary Entry for Thursday 15 May 1662,” http://www.pepysdiary.com/diary/1662/05/, date last accessed 8th February 2016.

[3] Lake Allen, The History of Portsmouth, (London: Hatfield & Co., 1817), 120, 125-127.

[4] “Catherine of Braganza,” https://www.tea.co.uk/catherine-of-braganza, date last accessed 8th February 2016.

[5] Wright, Domus Dei, 23.

[6] David Pepin, “Cathedrals of Britain,” (Oxford: Shire Publications, Ltd., 2016) 173-174.

[7] Pepin, “Cathedrals,” 174.

[8] “Imperial Royal Visit to Portsmouth,” The Times, 27th June 1814.

[9] “Funeral of Lieutenant-General Sir Charles James Napier,” The Morning Chronicle, 9th September 1853.

[10] “History of Royal Garrison Church, Portsmouth,” http://www.english-heritage.org.uk/visit/places/royal-garrison-church-portsmouth/history/, date last accessed 4th March 2016.

Comments are closed.