Given the upcoming centenary of the Great War this year it is understandable that we find ourselves saturated with discussions of the tragedy that befell the European empires in 1914. Yet, despite this wide and encouraging engagement with the topic, the key focus of popular debate is centred on the many millions who died fighting in the trenches. Once again the sailors of the Royal Navy are at risk of being overshadowed. Like their counterparts in khaki they too were brothers, fathers and sons who served and died for their country. The reasons for this overshadowing are too complex for an article of this brevity but with the growing interest in the personal lives of soldiers, and the digitalization projects currently underway, the opportunity is there for a similar investigation into the lives of sailors.[1]

Given the upcoming centenary of the Great War this year it is understandable that we find ourselves saturated with discussions of the tragedy that befell the European empires in 1914. Yet, despite this wide and encouraging engagement with the topic, the key focus of popular debate is centred on the many millions who died fighting in the trenches. Once again the sailors of the Royal Navy are at risk of being overshadowed. Like their counterparts in khaki they too were brothers, fathers and sons who served and died for their country. The reasons for this overshadowing are too complex for an article of this brevity but with the growing interest in the personal lives of soldiers, and the digitalization projects currently underway, the opportunity is there for a similar investigation into the lives of sailors.[1]

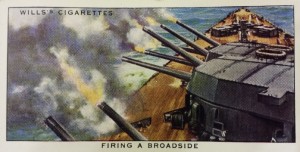

Mobilized across the world sailors took part in a wide number of activities during the war but what did they actually think about their involvement? What did they experience and how did they react to it? By examination of sailor diaries and testimonies it is evident that they had plenty to say on the subject of the war. In fact, the level of detail some sailors committed to paper stands in stark contrast to peace time entries.

Seaman Wood of HMS Ark Royal showed a good deal of interest in the opening attack on the Dardanelles. He noted they ‘anchored of [sic] Rabbit Island & witnessed the action. It was very exciting.’[2] Wood revealed a level of romanticism that could exist despite the carnage of battle brought together by the juxtaposition of exotic surroundings and war itself: ‘besides watching the pretty sights of shells bursting we have some sunsets out here worth seeing.’[3] He recorded the navy’s involvement in an easy manner and it is possible to see a sense of pride in what he was a part of. He noted an attack on HMS Queen Elizabeth with a degree of smugness: ‘several small guns fired at Queen E & she was hit 16 times but it was like throwing a flea at her anchor’.[4] Yet he also revealed the possibility for affinity with the enemy as he described an air raid by a German aeroplane: ‘it was a splendid fly and credit is due to him whoever it was.’[5] Similar occurrences of mutual respect were experienced amongst soldiers on the Western Front.[6]

Sailors were not alone in recording the interests of the war and other men who made up ships’ compliments also recorded their feelings. For example Stoker J. W. Payne talked of giving chase to German shipping. Payne demonstrated a stoker’s mentality in his writing and in particular he noted that they chased the Dresden but had to abandon the chase ‘on account of the failing light and shortage of coal.’[7] Coaling was an unpleasant task at the best of time and the need to coal increased dramatically during wartime as ships remained at sea burning more and more fuel. Stoker Jack Cotterell recorded a similar story on sighting two German cruisers: ‘Well, we stokers went mad, we made that much steam Captain Kelly had to phone down to tell us to slow down.’[8] Yet his excitement is clear in his comment:

Nevertheless, like soldiers, sailors had to face death or the prospect of death on a daily basis. Reflecting on the failure of the Gallipoli campaign, Ordinary Seaman Tom Spurgeon recorded: ‘I was a bit sad because it hadn’t been a success and there was a lot of death.’[10] Alfred Hutchinson recorded the devastation in more detail following an engagement near Zeebrugge: ‘there was just one big heap of arms and legs. My friend, he had his head blown off. He’d only got married on the weekend before we left.’[11] Death was an experience sailors had to come to terms with and repeated exposure caused a hardening humanity. On seeing a dead body drifting ashore at Gallipoli Wood stated, ‘I towed him out to sea again…’[12]

This article has tried to give a brief insight into sailor life during the First World War. It has shown the excitement and camaraderie felt by sailors but also their reactions to death in battle. Their involvement has too often been consigned a limited place in popular discourse on the Great War, but like those who served in the trenches, sailors deserve a greater place in British popular memory. As the centenary approaches, it is time for renewed interest in the role of those who served in the Royal Navy.

References

[1] The greatest naval engagement of the First World War was the Battle of Jutland which was viewed by many as a disappointment. One could conjecture if the battle had been a resounding victory like Trafalgar, British popular memory would have treated it more kindly.

[2] RNM 1984/467: Diary of Seaman Wood, 5.

[3] RNM 1984/467: Diary of Seaman Wood, 21.

[4] RNM 1984/467: Diary of Seaman Wood, 8.

[5] RNM 1984/467: Diary of Seaman Wood, 13.

[6] Joanna Bourke, An intimate history of killing: face to face killing in 20th century warfare, (London: Granta Books, 1999), 363.

[7] RNM 1982/189: Diary of J. W. Payne, 8 March 1915.

[8][8] Max Arthur, True Glory: the Royal Navy, 1914-1939, (London: Hodder and Stoughton, 1996), 22.

[9] Arthur, True Glory, 22.

[10] Arthur, True Glory, 47.

[11] Arthur, True Glory, 125.

[12] RNM 1984/467: Diary of Seaman Wood, 39.

Comments are closed.