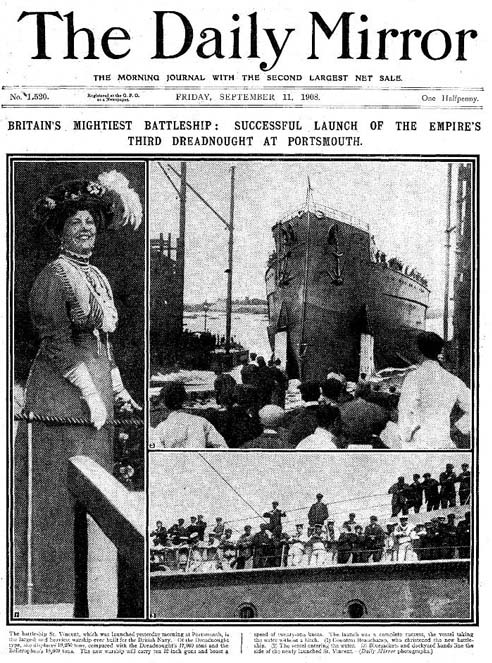

Launch of HMS St Vincent. Daily Mirror, September 1908.

During the nineteenth century pageantry became an increasingly important, ritualized facet of the Royal Navy and altered its relationship with the public.[1] Fleet Reviews no longer represented a true ‘inspection’ of the ship by the monarch but were a carefully choreographed spectacle designed to be witnessed by the public.[2] Similarly ship launches moved beyond the bounds of closed-off shipyards but became, as Margarette Lincoln opined, ‘exciting event[s]’ that drew large crowds together.[3] Yet, limited work has been undertaken on the complexities of pageantry and naval ceremony.[4] In particular, few have asked what sailors thought about the ceremonies in which they were often key participants. This article hopes to give a brief insight into how sailors viewed such events.

For men of the lower deck naval pageantry meant extra hard work. Jan Rüger gave the example of a stoker named Robert Percival who suggested, in his private diary, that there were persistent grumblings below deck during naval celebrations.[5] Percival emphasises this point: ‘to the man in the street, no doubt, [it] would be looked upon as a spectacle, but to the initiated, every smoking funnel meant Work’.[6] However, Rüger demonstrated that feelings of animosity were also combined with a sense of pride.[7] Other sailors are less forthright and it is the ‘silence’ that gives an insight into their thoughts.[8] For example Albert Kneller regularly described dressing the ship, always in a very matter-of-fact way without much enthusiasm or complaint.[9] Similarly, Edwin Fletcher mentioned dressing the ship for inspections and port visits with little enthusiasm, however he always kept a note of whom they saw and what the occasion was.[10] He recorded a visit on board by Queen Alexandra in 1905 in particular detail betraying some sense of his interest and pride.[11]

Therefore it can be suggested that there was no silent consensus amongst sailors.[12] Sailors did not necessarily keep their views to themselves. Instead, pageantry created a domain where ‘public appearances and private views could coexist.’[13] For the average man of the lower deck naval ceremonies meant extra work and harsh scrutiny, but they could still feel a sense of pride in the navy and in Britain.[14]

References

[1] For an understanding of ‘invented traditions’ see Eric Hobsbawm and Terence Ranger (ed.), The Invention of Tradition, (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2012 [first edition 1983]).

[2] Jan Rüger, The Great Naval Game: Britain and Germany in the Age of Empire, (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2009 [first edition 2007]); 16-17.

[3] Margarette Lincoln, ‘Naval Ship Launches as Public Spectacle 1773-1854’, Mariner’s Mirror, 83, 1997.; 466-472, 466.

[4] See Rüger, The Great Naval Game; Margarette Lincoln, ‘Naval Ship Launches’, and the unpublished D.Phil. by Silvia Rodgers, The Symbolism of Ship Launching in the Royal Navy, (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1983).

[5] Rüger, The Great Naval Game, 123.; RNM, 1988/294: Diary of Robert Percival.

[6] RNM, 1988/294: Diary of Robert Percival.

[7] Rüger, The Great Naval Game, 123.

[8] For further information on the dangers and limitations of using diaries see Christopher McKee, Sober Men and True: Sailor Lives in the Royal Navy 1900-1945, (London: Harvard University Press, 2002); 6-8.

[9] 207/90(1): Diary of Albert Kneller.

[10] 151/80(1): Diary of Edwin Fletcher.; 151/80(2): Diary of Edwin Fletcher.

[11] 151/80(1): Diary of Edwin Fletcher.

[12] Rüger, The Great Naval Game, 122.

[13] Rüger, The Great Naval Game, 124.

[14] Rüger, The Great Naval Game, 123.

Comments are closed.