The long nineteenth century was a period of substantial trial and error and steady development by the Admiralty in its efforts to create a centralised, well-trained and reliable naval reserve, which could be called upon to augment the fleets during an emergency. Between 1831 and 1903 the Admiralty undertook a variety of measures, with the assistance of various governments and acts of parliament, to create a viable reserve. As the studies of Jeremy Black, N.A.M. Rodgers and Brian Lavery show, this was not an easy task.[1] Several such bodies were created over the course of just seventy years some lasting for a century others for only a couple of decades. Although some of those various services were short-lived each played a role in the development of what became a professional volunteer career navy, long before the outbreak of the First World War.

The long nineteenth century was a period of substantial trial and error and steady development by the Admiralty in its efforts to create a centralised, well-trained and reliable naval reserve, which could be called upon to augment the fleets during an emergency. Between 1831 and 1903 the Admiralty undertook a variety of measures, with the assistance of various governments and acts of parliament, to create a viable reserve. As the studies of Jeremy Black, N.A.M. Rodgers and Brian Lavery show, this was not an easy task.[1] Several such bodies were created over the course of just seventy years some lasting for a century others for only a couple of decades. Although some of those various services were short-lived each played a role in the development of what became a professional volunteer career navy, long before the outbreak of the First World War.

One of those naval reserve forces, which can claim the title of the first true reserve of the Royal Navy, was the Royal Naval Coast Volunteers (RNCV). Although one might argue that this title can be claimed by the Coast Guard, and indeed it did perform a reserve function, it was not specifically established for that function. Rather it steadily developed it as the Admiralty steadily absorbed it form the Board of Trade between 1831 and 1852. In contrast, the RNCV was purposefully established on the recommendation of the 1852 Admiralty Commission on manning the Navy and by the Naval Coast Volunteers Act of 1853 as “a Coast Militia as a Part of a Naval Reserve.”[2]

It subsequently underwent a trial by fire during the Crimean War, before being later amalgamated into the Royal Naval Reserve in 1873. It was a central part of the navy’s and then the naval reserve’s evolution over in the long nineteenth century, and more especially from 1852. Yet to date very little has been written about it. Although Brian Lavery gave it a few pages in his 2007 work Shield of Empire: the Royal Navy and Scotland, other more general works on Britain’s and even Ireland’s maritime history as well as the histories of the Royal Navy more generally, have only given fleeting (if indeed any) attention to that force.

Although it was short-lived and indeed perhaps unsuccessful (but dedicated research is required to truly ascertain this), it was an official military service that was established by act of parliament and patronised by the monarchy; it certainly lay the foundations for the Royal Naval Reserve in 1859. Although I have not yet undertaken enough research to provide a complete and more importantly United Kingdom history of the service, at this time I aim to create a basic public awareness and knowledge of it, through a micro study of Ireland during the Crimean War.

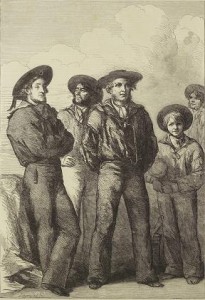

Having been sanctioned under the 1853 Act, the RNCV was established in January 1854. It was to consist of 10,000 men recruited from the seafaring and maritime communities of the United Kingdom and their enrolment, training, payment and the costs of their uniforms was to be provided through the £50,000 voted for by parliament. In that same month Captain Arthur William Jerningham, (pictured top left) recently the Inspector of the Coast Guard in Ireland was appointed as commander of the new service on that island and was tasked with the specific mission of raising 1,000 such men “from seafaring men on the coast[s].”[3] This complement of ten per cent was reflective of the island’s total contribution to the in-take of Royal Navy recruits in 1852 – evident from the same official report that instigated the foundation of the RNCV. Jerningham chose for his base of operations the city of Cork on the southern coast.

From there and during the spring and summer months of 1854 and 1855 Jerningham made several tours up and down the southern and western coasts; each time stopping at one of a combination of settlement. Having made some preliminary efforts throughout January, his efforts really began from the beginning of February 1854, following the navy’s mobilisation order. On the 1st he travelled from Queenstown up to Galway, stopping along the way at the towns of Tarbert, Kilrush, Carrigholt, in Kerry and Clare, and by the time that he returned to Cork around the 17th, he had according to The Times, “the satisfaction of numbering 252 able-bodied expert men and, young and middle-aged” in his force.[4] On that later date the Cork Examiner described the Merchant Marine Board at Cork as being “besieged by persons offering themselves” for service. On that day 100 men were passed by the doctor and enrolled.[5] Then between March and June he made three more trips. The first was in March when he travelled to Kinsale, Dingle, Kilrush, Kilkee and Carrigaholt, the second was in May when Askeaton, Dingle, Milton and Caherciveen were on his list. His last stop in June was solely to Castletownbere.

In 1855 a similar pattern was followed, although the reports in the press appear to have been far fewer in number; or he simply travelled less. Either way in April, and over the course of just two weeks, he was reported to have enrolled 72 men at Queenstown and 250 at Cork. Apparently, and according to the Freeman’s Journal, the “anxiety to enlist” was so great that many of the men reportedly ran after Jerningham “in the street requesting to be enrolled.”[6] Thereafter he made his way back to the Galway where he obtained a few more fishermen and turfboatmen from Lough Corrib.

Over the course of those two seasons, and with two exceptions in 1854, at Askeaton and Castletownbere, where he did not get any men (but the reception was still cordial), Jernigham was reportedly well received in every Irish locality. The only true exception to all of this was an alleged incident in late March of early April of that year, when the men of an unspecified parish (most likely in Kerry given the timescale) actually hid from him. According to the Cork Southern Reporter “the young men actually slept in haggards, and avoided their own homes … to escape the impressment, which they had been led to believe was contemplated.”[7]

Comical as this may seem to us today, what it shows is that the fear of the press-gang persisted long after its cessation. In fact as Brian Lavery has noted in the case of the Shetlands, it persisted right into the 1880s.[8] With that sole exception the contemporary newspaper reports describe Jerningham as being well-received, not only by the prospective volunteers, but also by their women folks, the local gentry and even the Catholic clergy. Indeed it was the later that proved to be most important as many if not most of those isolated communities did not speak English at that time. Thus, Jerningham actually required translation services during some trips. The one reported instance of this was at Dingle in late May 1854, where 80 men put themselves forward, after the Rev Eugene O’Sullivan had “explained to the fishermen, in an address in the Irish language, the rules and the nature of the service.”[9] Jerningham was assisted by the Rev Mr Kelleher at Kinsale and the Rev Mr Enright at Castletownbere, and the latter was reported to have actually addressed his congregation at the end of mass on the merits of entering the service.

The RNCV came into existence as an organisation only two months before the outbreak of the Crimean War. While the Admiralty endeavoured to get the severely under-manned navy up to establishment Captain A. W. Jerningham personally endeavoured to help raise the United Kingdom’s new defensive force (and potential recruitment ground, similar to the ‘land militias’). Not only were his efforts well-received by the people along the southern and western coasts but the final tally of recruits illustrates his success. He was tasked with enrolling 1,000 Irish seafaring men for the then newly established 10,000-man force – 10%. This was reflective of the island’s 1852 contribution to the Royal Navy. According to the reports of the contemporary newspapers Jerningham successfully enrolled 1,078 men between February 1854 and June 1855, out of what turned out to be a total force of only 2,300 in the whole United Kingdom during the war. Evidently the RNCV was a failure in Britain, but in Ireland not only was it successful, it was evidently very popular

The RNCV came into existence as an organisation only two months before the outbreak of the Crimean War. While the Admiralty endeavoured to get the severely under-manned navy up to establishment Captain A. W. Jerningham personally endeavoured to help raise the United Kingdom’s new defensive force (and potential recruitment ground, similar to the ‘land militias’). Not only were his efforts well-received by the people along the southern and western coasts but the final tally of recruits illustrates his success. He was tasked with enrolling 1,000 Irish seafaring men for the then newly established 10,000-man force – 10%. This was reflective of the island’s 1852 contribution to the Royal Navy. According to the reports of the contemporary newspapers Jerningham successfully enrolled 1,078 men between February 1854 and June 1855, out of what turned out to be a total force of only 2,300 in the whole United Kingdom during the war. Evidently the RNCV was a failure in Britain, but in Ireland not only was it successful, it was evidently very popular

Between 1854 and 1855 Ireland’s maritime community, along its southern and western coasts, showed substantial interest in and enthusiasm for the new ‘Sea Militia’. However, such interest does not represent a lack of enthusiasm for the war nor a desire to hide at home in the reserve. Ireland no doubt provided its fair share of the 13,000-odd Royal Navy recruits enrolled during the war (although precise figures are lacking). The new reserve service was specifically geared towards those men – fishermen etc. – and their primary function, once the Coast Guard had been drafted into the regular service, was to provide coastal defence. A comparable enthusiasm was also shown by ‘landsmen’ towards the army militias in 1855 and 1856.

The poor take-up of the RNCV in Britain can be seen as part of a much broader problem of manning the Royal Navy and the Royal Marines during the war, as well as in the wider nineteenth century. That being said, the actions taken in 1858-9 – the establishment of the 1858 Commission for the Manning of the Navy, the passing of the Naval Reserve Act and the foundation of the Royal Naval Reserve both in 1859 – were a complete repetition of those in 1852-3. The Royal Naval Reserve was not the first definitive attempt by the Admiralty to establish a centralised and nationwide naval reserve. Excluding it two-decade-long steady absorption of the Coast Guard – taking it away from the Board of Trade – the very first reserve, however limited, was established six years previous and was embodied in the largely forgotten and certainly overshadowed Royal Naval Coast Volunteers.

For more on this see Paul Huddie, British Journal of Military History, Vol. 2, Issue 1 (October, 2015) and Paul Huddie, The Crimean War and Irish Society (Liverpool: Liverpool University Press, 2015).

Notes

[1] Jeremy Black, The British Seaborne Empire, (New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 2004); N.A.M. Rodger, The Command of the Ocean: a Naval History of Britain 1649-1815, (London: Penguin, 2005); Brian Lavery, Shield of Empire: the Royal Navy and Scotland (Bilinn Limited: Edinburgh, 2007).

[2] Copies of a correspondence between the Board of Treasury and the Board of Admiralty on the subject of the manning of the Royal Navy, together with copies of a report of a committee of naval officers, and of Her Majesty’s order in council relating thereto, 27, [1628], H.C. 1852-53, lx, 9

[3] The Times, 7th February 1854.

[4] The Times, 3rd February 1854.

[5] Belfast News-Letter, 22nd February 1854.

[6] Cork Examiner, 2nd May 1855.

[7] Manchester Times, 15th April 1854, citing Cork Southern Reporter.

[8] Lavery, Shield of Empire, 153.

[9] Cork Constitution, 2nd February 1854

Comments are closed.