In The Myth of the Press Gang, J. Ross Dancy offers a quantitative approach to the subject. He developed a sampling system and entered the details as recorded in individual ships’ muster books covering the period 1793-1801. Data entry took twenty two weeks. The end result was a database including 27,174 individuals, “roughly a 10 per cent sample of men recruited into the Royal Navy” in this period.[1]

In The Myth of the Press Gang, J. Ross Dancy offers a quantitative approach to the subject. He developed a sampling system and entered the details as recorded in individual ships’ muster books covering the period 1793-1801. Data entry took twenty two weeks. The end result was a database including 27,174 individuals, “roughly a 10 per cent sample of men recruited into the Royal Navy” in this period.[1]

Dancy concludes that “the number of volunteers serving on British warships was two or three times higher than had been previously considered.”[2] Some have already suggested that this book is a decisive intervention in the way that we think about the institution of impressment.[3]

Key contentions

There is always the risk, in a critical review, that the response to the book obscures the message of the book itself. Myth of the Press Gang argues the following:

* Impressment was the solution to the Navy’s key manpower problem, obtaining able seamen.[4] Problems of “wastage,” defined as “sickness, injury, death, or desertion” existed, but remained at low levels.[5]

* “Few pamphleteers had a good grasp of the problems involved in naval manning,” and naïve assumptions abounded, notably that the Navy had a bottomless supply of trained seamen to draw upon.[6]

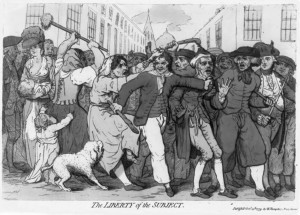

* The typical operations of the press gang were orderly, nonviolent, and quite successful despite some moments of “social friction” in port towns.[7] Considered in proportion to the volume of men that impressment took, even “affrays” did not cause much of a problem, amounting to 1 incident per 750 men taken, using Rogers’ own figures.[8]

* While impressment was unloved, it was not deeply controversial. A broad consensus existed—even among sailors—that it was a necessary evil. The modern myth of the press gang is a late arrival, dating from the 1830s, “when naval manning procedures were vilified in order to support the arguments of radical politicians.” [9]

* The heated rhetoric of the 1830s has been perpetuated in an unbroken line of succession, with books quoting other books: impressment was a “tyrannical and evil implement,” the gangs themselves were “brutal.”[10] He identifies John Masefield’s 1905 book Sea Life in Nelson’s Time as an important influence on the historiography up to the present.[11]

* To the extent that they are not recycling old myths, historians have been deceived by the “trap” of malcontent sources.[12] Relying on “opinions” from the time, such as autobiographies and material from newspapers and attention-seeking controversialists will always privilege the exceptional case and does not give us a picture of everyday activity.[13]

* Impressment, according to the muster books, made up 16% of the recruits for 1793-1801 as a whole, although disaggregating the years showed rising numbers of pressed men towards the end of that period (all the way up to 27% in 1801).[14]

For Dancy, the bottom line is unit cohesion and combat effectiveness.[15] If the Navy passes on those grounds, then it indicates that dissent, if present, was unimportant and is really beneath our attention. “Warship crews had respect and pride, both in themselves and their ship, and under high-quality leadership they were not unhappy… The experience [of esprit de corps], which is difficult to understand for those who have not undergone it, has transcended generations, and many historians have been oblivious to it when they have written the history of men of the lower deck.”[16]

A bottomless pot?

A comparison of the bullet points above with the work by Rogers and Brunsman, or even my short summary of their work in Part 1 of this review, will immediately suggest some trouble spots. I will not belabor all of them here. I’d like to spend some time, though, on the contention that the Navy’s critics imagined it could draw on a bottomless pot of skilled seafaring labor.

A comparison of the bullet points above with the work by Rogers and Brunsman, or even my short summary of their work in Part 1 of this review, will immediately suggest some trouble spots. I will not belabor all of them here. I’d like to spend some time, though, on the contention that the Navy’s critics imagined it could draw on a bottomless pot of skilled seafaring labor.

Dancy is quite vehement on this point:

“These pamphlets also almost always assumed that the number of seamen available for naval service was unrealistically large or virtually unlimited and that there was a shortage of volunteers.”[17]

“… it was commonly believed that seamen were so numerous as to be virtually infinite…”[18]

“Nearly every commentator overlooked the primary problem of naval recruitment, a shortage of skilled labor, assumed that the supply of seamen was limitless, and therefore focused on attracting men to naval service.”[19]

I found these statements surprising, since pronatalist proposals to somehow foster Britain’s “nursery of seamen” were common in the anti-impressment literature. The premise was that only trained seamen would do, there weren’t enough of them, and an organized, long-term program to increase the number was the path forward. Suggestions for model villages and land allotments emerged in the 1750s and proved remarkably persistent, including Jonas Hanway’s bizarre idea of pairing off “sailors just landed” with reformed prostitutes.[20] “What becomes of the offspring of most of our sailors? the solution would puzzle beyond most questions in algebra,” wrote Philo Nauticus.[21] This focus on infancy and child rearing does serve as a reminder that these proposals were part of a larger pattern; the 1750s also gave us Thomas Coram’s Foundling Hospital, not to mention Hanway’s own Marine Society (itself a response to the shortage of skilled seafaring labor).

One measure of how mainstream the “nursery of seamen” thinking became is that John Knox’s proposal for model villages was actually funded and implemented. Knox came to London in March 1786 to promote his plan for forty new fishing villages spaced at intervals of twenty-five miles along the thinly populated coast of northern Scotland. Why was this worth the trouble and expense? Knox’s language drew heavily on the “nursery of seamen” argument; it was imperative to keep sailors close to home and improve the environment in which their children would grow up. The fishing villages would form a reservoir of experienced seafaring men who would be available at the outbreak of any future war with France. Founding overseas settlements, he wrote, would not serve the same purposes; distant settlements were hard to defend and would not furnish sailors to defend Britain’s home waters in a hurry.[22] Under the auspices of a newly-formed private joint-stock company, the British Fisheries Society, and Thomas Telford, one of the great civil engineers of the era, the planned communities of Ullapool and Tobermory were established two years later.[23]

It’s hard to see what could have animated this fierce interest in Britain’s “nursery of seamen” other than an awareness that skilled seafarers had to be bred to the job, it took years, and there was a finite supply of such men.

If, for the sake of argument, the 1830s were the crucial turning point in the conversation about impressment, how did the rhetoric of the 1830s differ from what went before? The chapters in the classic edited volume The Invention of Tradition offer an excellent template for this kind of project.[24] What readers will expect is a sequence like this: here’s the pamphlet attributed to Vice-Admiral Knowles from 1758; here’s the speech by Temple Luttrell in Parliament from the 1770s; here’s the petition against impressment from the sailors of Newcastle in 1793; here’s what Mary Wollstonecraft wrote against impressment; here are the articles from the Independent Whig on flogging and impressment from the summer and fall of 1816; here’s the twenty-seven page discussion in the Edinburgh Review of 1824, reviewing five publications that had appeared on the topic in the last ten years and applying new concepts from political economy to the labor supply problem; with all that in mind, here’s the dramatis personae of the 1830s, what they said, what was new, what motivated them in saying it, and why it took hold of the popular imagination like nothing before it.[25] We don’t get anything resembling this from Dancy.

One thing that many historians will notice immediately about Myth of the Press Gang is that it’s a book with politics at its very heart, written by someone profoundly uncomfortable with the concepts and source material of political history. However, discounting some of these claims doesn’t address the book’s major contentions, which are about numbers. It makes sense to spend proportionately more time on these.

Undercounts and overcounts

One of Dancy’s preferred terms for his method is that it is statistical. A hallmark of the academic disciplines that use quantitative evidence is a concern about the validity of particular types of measurements; the meticulous collation of records that themselves systematically undercount something, or offer an inflated figure, only reproduces the bias. The result is a false appearance of precision. Podcasts like the BBC’s More or Less are never short of material, because it is a rare statistic that can’t be disputed. Historians are right to be a bit suspicious of anyone who presents counting as a straightforward activity.

One of Dancy’s preferred terms for his method is that it is statistical. A hallmark of the academic disciplines that use quantitative evidence is a concern about the validity of particular types of measurements; the meticulous collation of records that themselves systematically undercount something, or offer an inflated figure, only reproduces the bias. The result is a false appearance of precision. Podcasts like the BBC’s More or Less are never short of material, because it is a rare statistic that can’t be disputed. Historians are right to be a bit suspicious of anyone who presents counting as a straightforward activity.

Myth of the Press Gang is principally concerned with two numbers: the Rogers figure for press gang riots, which he takes as proof that impressment did not generate significant opposition or involve major disruptions, and Dancy’s own high volunteer figure from the muster rolls, which he takes as proof that most sailors were in the Royal Navy because they wanted to be there.

It seems unlikely that we will ever have a complete list of riots against the press gang, if only because the gangs had a disincentive to report their failures and embarrassing defeats in the face of often quite humble civilian opponents. Lieutenant John Mitchell was attacked while on duty in South Shields on 19 April, 1803 by “a Multitude of Pilots and Women, who threw a quantity of Stones and Brickbatts at him, they likewise threatened to hew him down with their spades…” Lest a spade in the hands of a woman not sound sufficiently threatening to his superiors, Mitchell elaborated, explaining that spades “are very dangerous Weapons, they being round and quite sharp with Shanks of about six feet in length…”[26] Sailors routinely took jobs on farms and in quarries to evade impressment, leading the press gang to venture inland. In Barking, a press gang captured some sailors, only to be set upon and defeated by “a numerous body of Irish Hay-makers, armed with Sabres and pitchforks…”[27] The portentous capital letter notwithstanding, it seems likely that these “Sabres” were just sickles. Easier, surely, to say “what happens in Barking stays in Barking”?

There’s a bigger problem with measuring resistance only by looking at a total of riots, which were only the tip of the iceberg. One of the most persistent types of complaint that reached the Home Office was about nonviolent, yet infuriatingly effective, obstruction by local officials: mayors who refused to talk down angry mobs, magistrates who wouldn’t back the press gang’s warrant or publicly stated that impressment was illegal, constables who would arrest members of the gang but turn a blind eye to its antagonists, and so forth.[28] The sort of evasion tactics and merry chases that I discussed in Part 1 of this review won’t usually have counted as riots, either.

Both officials and crowds engaged in brinkmanship, seeking to obtain concessions while leaving the consequences of refusal at least partly up to the imagination. In January 1793, Peter Rothe reported one such tense negotiation to the Home Office. He’s worth quoting at length:

…the Seamen of this Port here collected themselves into a large Body parading the Streets of Newcastle for these two days past and remained together at a place called the Forth Close by my lodgings, for many hours each day that I acquainted the Magistrates with the circumstance and requested that they would disperse them if possible… but they not dispersing I went to them myself this Morning and desired to know what was their reason for assembling in so large a number, their answer to me was that they were resolved to protect themselves from being impressed and that they were resolved to a man to lose their lives before they would be impressed, they likewise desired that I should discharge the Gangs. I told them that I had no orders to impress, I only wanted volunteers and that I would not discharge the Gangs, they then asked me, that if I should receive a Warrant to Impress whether I meant to do it, I told them I most certainly would do my duty when ordered, they told me they would oppose every attempt of the kind at the risk of their lives, but said they had no objection to my raising as many volunteers as I could get…[29]

Anonymous threatening letters (one complaining how impressment was “Distressing fammilys without number”) found their way to the doorstep of rendezvous houses, but also to softer targets.[30] In 1793, one “Mr. Goodere,” a printer in Swansea who had volunteered “to be master of ye Press Gang” was taunted with the prospect that “you’ll find your house pulled about your ears, by ye unanimous multitude” if he persisted in “that diabolical act” on behalf of “a war, which more than half ye nation think to be most unjust & unnecessary, and carried on with no other real intention, than to support Popery and Despotism, and to stop the progress of civil & religious liberty…”[31] Some kept their nerve under the pressure, while others started looking for the exits. Captain Samuel Cable wrote to Evan Nepean from the Isle of Man in 1798, complaining that “the Country has been in a constant state of fermentation” after fishermen had been impressed by a ship called the Spider, and there had been talk of tarring and feathering him. “As this commotion does not seem likely to subside soon,” Captain Cable asked if he could fill “the first vacancy that offers” that would remove him “to any part of Great Britain.”[32]

In my book, I mentioned the 1811 incident on the Isle of Man when a crowd of five hundred, armed with sharp sticks, waited until low tide and then charged the tender where thirty-three local men were confined, shouting “burn her, sink her, burn her” until Lieutenant Commander Thomas Hawkes felt he had no choice but to open fire on the mob.[33] I suppose from Dancy’s point of view, this counts as one incident of rioting against the press gang. There’s a big difference between counting riots and reading about riots as methods here. In the archives, the explosion of violence is often described as the culmination of a long process or the “last straw” moment (either for the Navy, or from the locals’ point of view). The tavern-keeper or insouciant magistrate is someone whose insufferable conduct should have been reported long ago. The town is, has been, will be a nightmare for anyone with a press warrant. In the case of the Isle of Man, letters had been reaching the Home Office for twenty years before the 1811 incident concerning the bitter dispute brewing over exemptions for seasonal herring fishermen.[34] From the local perspective, an on-again, off-again exemption was perhaps even more infuriating than no exemption at all. I have already mentioned Captain Cable, who wrote from the Isle of Man begging for a transfer in 1798. I’m not comfortable with a calculation that assigns the 1811 incident a value of “1” and moves on.

In my book, I mentioned the 1811 incident on the Isle of Man when a crowd of five hundred, armed with sharp sticks, waited until low tide and then charged the tender where thirty-three local men were confined, shouting “burn her, sink her, burn her” until Lieutenant Commander Thomas Hawkes felt he had no choice but to open fire on the mob.[33] I suppose from Dancy’s point of view, this counts as one incident of rioting against the press gang. There’s a big difference between counting riots and reading about riots as methods here. In the archives, the explosion of violence is often described as the culmination of a long process or the “last straw” moment (either for the Navy, or from the locals’ point of view). The tavern-keeper or insouciant magistrate is someone whose insufferable conduct should have been reported long ago. The town is, has been, will be a nightmare for anyone with a press warrant. In the case of the Isle of Man, letters had been reaching the Home Office for twenty years before the 1811 incident concerning the bitter dispute brewing over exemptions for seasonal herring fishermen.[34] From the local perspective, an on-again, off-again exemption was perhaps even more infuriating than no exemption at all. I have already mentioned Captain Cable, who wrote from the Isle of Man begging for a transfer in 1798. I’m not comfortable with a calculation that assigns the 1811 incident a value of “1” and moves on.

In considering how to read the archival traces left behind by the press gang, we also need to be sensitive to which events would have mattered enough to the Navy to merit the application of pen to paper—and which wouldn’t. Mistaken arrests, for example, may have been corrected before anyone was entered in a muster book, but that doesn’t mean they didn’t occur, and leave a lasting impression. Scottish children played a variant of tag that they called “press gang the weaver.”[35] In his memoirs, the boxer Daniel Mendoza related how he was celebrating Purim—a carnival-like Jewish holiday with costumes and noisemakers—with all his friends dressed up like sailors. They encountered a press gang and according to Mendoza, spent two days locked up before it was sorted out.[36] Incidents like these—unless they resulted in lawsuits—aren’t likely to reach us in any form other than the faint signal of popular memory, autobiographical anecdotes, and the occasional newspaper item. Brunsman found many examples of “catch and release” tactics that involved rounding up many men at once and sorting them out later, with reject rates of 75% or even 90%.[37] If we care about how ordinary bystanders perceived the press gang, these sorts of tactics did have consequences. It certainly has to figure into our assessment of whether or not impressment was disruptive.

What, then, of the muster books? It’s interesting that Rogers and Brunsman are not as sanguine as Dancy about using naval records to reconstruct an exact figure. Brunsman states that “the navy did not make hard distinctions between forced men and volunteers in its own accounting,” while according to Rogers, “muster books prove something of a dead end when it comes to calculating the proportion of men pressed into the navy.”[38] If these books had been published after Myth of the Press Gang, I am sure they would have elaborated what they have in mind here. Brunsman mentions some helpful reference points, though. In Dublin, one cunning press gang officer got men to volunteer, but only by threatening to turn them over to the army if they didn’t.[39] Admiral Philip Cavendish offered a more general comment: “they are all Voluntiers as soon as they can find they can’t get away.”[40]

These two examples are from the 1740s, but they speak to a very pertinent problem with Dancy’s numbers: How are we to separate the volunteers from the “volunteers”? A roster of recruits looks as objective as an inventory taken in a storeroom—there it is, plain as parchment—but there are some noteworthy differences. An error or a falsehood in an inventory might come back to haunt the record keeper (maybe the shipyard runs out of timber, or the clerk is accused of theft). Getting the ratio of volunteers to pressed men wrong was not going to get anyone in trouble. If, as N.A.M. Rodger has written, “impressment had no friends, least of all among naval officers,” that suggests to me, at least, a climate in which—without any directive from on high—it would be quite natural to count every last plausible recruit as a “volunteer,” and hand out whatever enlistment bonus might be on offer, as long as they had not offered serious physical resistance.[41] In a way, sailors may have been willing accomplices here. Even the lad who’d led the press gang on a merry chase could salvage his pride by volunteering at the last minute. The most effective white lie is the one that leaves everyone feeling better.[42]

Dancy doesn’t explain why he chose the 1790s for his sample, but this seems to have been a period where volunteers were easier to come by than later on. Brunsman mentions a figure of 75% impressed by the end of the Napoleonic Wars.[43] If, for the sake of argument, we accept a figure of 18% and apply it consistently across the Napoleonic Wars, some other questions arise. Just to consider some round numbers, the Navy peaked at around 140,000 men circa 1810.[44] If 18% of that figure was pressed, that would be 25,200. However, according to Paul Gilje “as many as ten thousand American seamen” were impressed in the years leading up to the War of 1812. Are we ready to accept that almost half of the pressed men were American?

It’s possible that the high American figure was part of someone’s dodgy dossier to justify a war. Gilje, however, adduces several different kinds of archival sources to support it, such as the notifications of individual impressments sent by the U.S. State Department to Congress beginning in 1797, and the official protests lodged by U.S. diplomats about particular cases. He also draws attention to the sheer volume of the seamen’s protection certificate applications, and remarks that impressment was a winning political issue in the U.S. because “many Americans knew or had heard of someone who had been impressed or threatened by impressment.”[45] Meanwhile, we’d need to cross-reference the American numbers with the testimony from individual British ports. Rogers made use of parish archives and municipal archives, for example, to arrive at assessments like this: “On Tyneside, poor relief tripled in the early 1790s to accommodate the families of seamen or keelmen taken up by the press.”[46] If we tally up what each of the individual British port towns say they lost to the press gang, and add on what the U.S. sources say, how large will that figure be? Others will examine the numbers here more closely, but an unintended consequence of Myth of the Press Gang may be to open up an interesting plausibility contest between the muster books and a variety of other primary sources.

“Unpopular government practice not all that common, official statistic reveals” sounds like a headline from The Onion. Questions were raised in Parliament on occasion; can we find examples where the Navy shot back “well, actually we only press 1 in 5 sailors”? They wouldn’t have had to commission a massive fact-finding inquiry to generate some good rough figures. They could have brought out a few ships’ muster books and claimed that they were representative examples. Often in pamphlet wars even the opposition arguments are reproduced (perhaps only to deride them, but sometimes in great detail), yet I don’t recall seeing this kind of point discussed in the anti-impressment literature. It also begs the question of why pro-impressment writers took the paths that they did. Charles Butler’s learned treatise from the 1770s extended to 63 pages, ranging over natural law, the Greeks and Romans, and medieval precedents.[47] If you’re defending an unpopular practice that you know is uncommon, don’t you open by pointing that out?

The volunteer figure is almost certainly soft at the upper end, and it will be difficult to generate consensus about just how much of it should be discounted. It would be nice to get a quick and certain resolution here, but the questions about naval recruitment are probably not amenable to a brute-force digital solution. Funding someone to digitize another few thousand muster books is not the way to remove concerns about reliability. I’m reminded of the old philosopher’s joke about the man who wasn’t sure the newspaper was an accurate source, so he went back to the newsstand and bought one hundred additional copies of the same newspaper to check.

The missing middle

Denver Brunsman refers to historians who feel obligated to act as the Navy’s “apologists,” and Myth of the Press Gang offers an instructive example of the ways that parti pris scholarship can be self-defeating. A lot of readers will quickly lose patience with Dancy’s consistent practice throughout of designating his approach as “modern” and that of his opponents as “antiquated.”

Denver Brunsman refers to historians who feel obligated to act as the Navy’s “apologists,” and Myth of the Press Gang offers an instructive example of the ways that parti pris scholarship can be self-defeating. A lot of readers will quickly lose patience with Dancy’s consistent practice throughout of designating his approach as “modern” and that of his opponents as “antiquated.”

Dancy chooses to adopt a number of positions that are extreme and very hard to defend, but takes pains to assert them aggressively, putting the weakest of them on the same footing as the ones where he believes he has extensive quantitative evidence. All of the press gang’s detractors thought there was a bottomless pot, except they didn’t. Impressment was not disruptive and controversial, except it clearly was. It wouldn’t have diminished Dancy’s contribution on the muster books to concede the points that he was going to lose on in any case.

When we say, as Brunsman does, that this conversation has gotten too polarized, that’s another way of suggesting that not enough scholars have staked out the territory in the middle. I agree with him that there’s a lot of untilled fertile ground in that middle range. Here’s at least a sketch of what that might look like:

* We already knew that there were a lot of volunteers, and we won’t understand this period until we’ve taken a close look at what motivated them. This follows logically on the path set out by Linda Colley in Britons: Forging the Nation a generation ago.

* If we take on board Dancy’s comments about elite units, then we need to balance that by taking the appeal of privateering seriously too. It was possible to experience esprit de corps elsewhere.[48]

* Whether or not we accept Brunsman’s thesis about masculinity and freedom in the Atlantic world, more work could be done on why naval service seemed worth evading. There was a robust market in fake impressment exemptions from America; if the Royal Navy was offering such a good deal, don’t we need to explain what motivated people to spend money in an effort to stay out of it?[49] When we read about sailors voluntarily curtailing their “Atlantic” freedom by picking voyages and itineraries to avoid ports known for press gang activity, what was at work here?[50]

* If we’re going to commit seriously to understanding the volunteers, we need an equal commitment to understanding the evaders and deserters. There’s no reason to assume they were all Jacobins. Some took a laddish pride in skill, both in running and in fighting. Others calculated that the risk of disease (Caribbean voyages) and scurvy outweighed any benefits of being in the Navy.[51]

* Once in the Navy, sailors reacted in varying ways; some volunteers became disillusioned. It’s interesting that some of the same practices trotted out by Dancy as an example of the system working well, like the practice of “turning over” crews, are noted by Brunsman as sources of resentment.[52]

* For the reasons discussed in Part 1 of this review, communities resented the press gangs and often united against them.

Another aspect of the middle position, I think, would involve making more room for ideology, both loyalist and dissenting, in shaping why we think the recruitment (and desertion) numbers look the way that they do. As someone who’s written about popular patriotism, I was surprised that it hardly makes an appearance in a book that argues there were even more volunteers than we thought. If the debate is expressed only in terms of “were they well fed and well led,” that risks infantilizing men who may have had views about the wars and what was at stake in them. Low desertion rates may have something to do with the fear of what a French invasion would mean for loved ones. Volunteering may have been an endorsement of the Royal Navy’s incentive structure, as Dancy proposes, or it could have been as much or more an indictment of the enemy and the values that enemy was thought to represent.[53]

If I can write at length about the mindset of loyalists, pious evangelical sailors, advocates of imperialism, quoters of Charles Dibdin lyrics, defenders of impressment, and the “patriotic complaints” of men who simultaneously respected the established order and were genuinely frustrated with its injustices and shortcomings, then surely there’s a naval historian who can do the same for deserters and radicals.[54]

Brunsman remarks that there is no plaque or monument to the men who ran, fought, and in some cases even died resisting impressment. Another group that lacks a monument, as far as I know, is the naval officers who improvised solutions in a difficult situation, arguing with local magistrates and people threatening lawsuits, and enforcing a policy that some of them personally found reprehensible. I think there’s an interesting paradox for naval historians here. The more that impressment is portrayed as relatively orderly, minor, and uncontroversial, the harder it becomes to appreciate the complexity and the danger of the challenges that frontline recruiters faced.

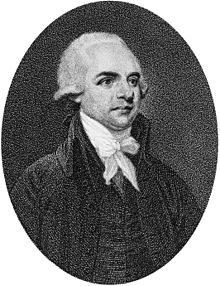

Similarly, the more dogmatic the insistence becomes that the critics of impressment were incompetent or greedy attention-seekers, the more the naval officers who took the time to write or speak against impressment will be consigned to a sort of historiographical limbo. One voice from the 1790s that deserves a hearing is Thomas Trotter’s. This Edinburgh-trained doctor rose to become Physician to the Channel Fleet by 1794.[55] His attention to supplying the fleet with fresh produce to combat disease, and his concern for the conditions in (and around) naval hospitals reflected his serious commitment to getting, and keeping, men fit for duty.

Similarly, the more dogmatic the insistence becomes that the critics of impressment were incompetent or greedy attention-seekers, the more the naval officers who took the time to write or speak against impressment will be consigned to a sort of historiographical limbo. One voice from the 1790s that deserves a hearing is Thomas Trotter’s. This Edinburgh-trained doctor rose to become Physician to the Channel Fleet by 1794.[55] His attention to supplying the fleet with fresh produce to combat disease, and his concern for the conditions in (and around) naval hospitals reflected his serious commitment to getting, and keeping, men fit for duty.

Trotter thought that the problem of pressed men giving in to illness was serious enough that he discussed it in his textbook, Medicina Nautica. Among “the evils of impressing,” Trotter mentioned how “persons of all denominations are huddled together in a small room, and the first twelve months of a war afford a mournful talk for the medical register, in the spreading of infection, and sickly crews.”[56] Beyond this, however, he discussed its effect on mental health, from despondency—which left sailors susceptible to other illnesses—to leaving a “mind diseased” with hatred.[57] For Trotter, impressment was “a most fatal and impolitic practice… the cause of more destruction to the health and lives of our seamen, than all other causes put together.”[58] This technocratic critique of impressment deserves a place in the story; it’s hard to hear voices like Trotter’s, though, if we are wedded to the idea that the press gang’s critics must have been ignorant, incompetent, and out to sell newspapers.[59]

Conclusion

I ended Part 1 of this review with some discussion of the big picture, and it makes sense to return to some of those themes now. As it happens, while I was working on this piece a reviewer’s copy of Adam Zamoyski’s Phantom Terror: Political Paranoia and the Creation of the Modern State, 1789-1848 came across my desk. Riots against the press gang actually make a very brief cameo appearance in this volume. In the summer of 1794, Pitt’s cabinet discussed a host of domestic threats, from “a plot to kill the king by firing a poisoned dart at him from a brass tube” to the more organized efforts of the London Corresponding Society. Alongside these, “riots against the press gangs were represented as being politically motivated…”[60] Zamoyski, in keeping with his overall thesis, is inclined to see this as just more evidence of a misguided siege mentality. It’s interesting to consider it, though, in the context established by Rogers’ tabulation showing that riots against the press gang were among the most common (and by far the most violent) crowd actions out there. If revolution had come to Britain, it could well have started with an anti-impressment riot that was suppressed at gunpoint by a panicked official.

Let’s face it, most of the time, most people are pretty politically inert—that’s one reason why motivated minorities can become so important. I’m not sure how we’d teach British history with the Nonconformists left out; or the Scots, for that matter. Minorities can also form coalitions of convenience, creating a new majority seemingly from nowhere, overnight, like crystals forming in a liquid solution.

There is, of course, a whole methodology that has developed to deal with the special problems of seeking out sources and voices from minorities, particularly in societies where they had limited access to publishing and other media. The marginal or the marginalized will simply not leave an archival record as profuse as that of the bureaucrats and money-counters. If we aren’t sensitive to this, minority opposition (deserters, dissenters, mutineers, radicals, reformers) will always appear as nothing more than bugs on the windshield of the fiscal-military state.

Dancy has succeeded in putting the relative frequency of impressment on everyone’s radar. I expect that Myth of the Press Gang will be the book that launches many doctoral dissertations, some in sympathy with its aims, others hostile to them, each trying to measure this differently, or better, in various ways and in different time periods. I don’t expect agreement any time soon. In the meantime, though, if impressment was relatively uncommon, does it necessarily follow that the opposition to it was founded on a “myth”?

The philosophers and reform-minded people who objected to the press gang did so not because it was common, but because they believed it to be egregiously and unforgettably wrong. That’s perhaps the essence of a cause célèbre, which is not the same thing as a myth. What bothered Hume, Voltaire, and many less famous individuals about impressment was that it happened at all. Consider how much ink Voltaire spilled on the Calas Affair, in which a Protestant father was falsely accused of murdering his son because the boy had announced his intention to convert to Catholicism. To suggest that the great majority of Protestant parents in France weren’t accused of murdering their children would miss the point.

Dancy does acknowledge in passing that impressment looked absolutist, though he doesn’t explore the implications of this. Thomas Trotter, again, is a voice worth considering. What a ghastly sight impressment was, he wrote in the mid-1790s, in a “country, that boasts so justly of her civil rights.”[61] Twenty years later, he was still passionate on the issue. “The very name of a Press Gang,” Trotter wrote, “carried in it something opprobrious: it is revolting to the feelings of a Briton; for no man who values personal security to himself [sic] can see it violated in another without detestation.”[62] The power of spectacle is key here; it’s one thing to know that such things happen somewhere, it’s another to witness it in front of you. Thus, the public, urban nature of the practice was part of the problem. Others worried that it fed the propaganda machine of the enemy.

Paul Gilje has traced the ubiquity of the “Free Trade and Sailors’ Rights” slogan in the United States, sometimes in jokes and generic tub-thumping political speeches, but also in contexts that packed more of a visceral punch: “By the end of the War of 1812, a banner with the slogan flew in proud defiance on a battery protecting the burned ruins of the White House, and intrepid sailors had written the words across the ‘star spangled banner’ as they raided British commerce in the English Channel.”[63]

Characteristically, when Dancy says that the press gang was cheap or cost-effective, he reckons this in terms of pounds, pence, and person-hours but not in terms of how impressment figured in relationships with North America, the tenor of life in individual port towns, or Britain’s carefully cultivated self-image.[64] This is the predictable result of naval historians asking naval questions of naval archives whose capacity for answering the worthwhile questions is taken as self-evident.

There’s an opportunity here for a new generation trained a bit differently, naval historians who are genuinely comfortable and well-versed in themes, sources, and methods that did not originate in naval history, and mainstream historians who are fluent and competent with Admiralty archives. It’s not so far-fetched; history of science and history of medicine are two subfields that are highly technical in nature, yet they have adapted and benefited greatly from cross-fertilization, to the point that it is often hard to tell where the subfield, in a purist sense, leaves off and mainstream historiography begins.

I am left wondering what sort of digital project on impressment would command the level of respect that the Transatlantic Slave Trade Database receives. I doubt that the TSTD’s degree of certainty is a realistic goal, but maybe a different design would help bridge some of the gaps between historians on this issue. It would involve digitizing not only the relevant muster books for a span of years, but also the reports surrounding how those recruitment efforts were received locally (in both ADM and HO papers). Another layer of that database would be the claims of impact (and statements about numbers) from local government sources, such as the parish and municipal records used by Rogers. It would also be helpful to see the dates of those recruitment and impressment drives cross-referenced with politics and news of the day so we see the climate that shaped compliance and non-compliance alike. Against all of this could be set the ebb and flow of desertion, of rumors of sedition in the fleet, and of actual mutinies. I’d love to the read the book based on that project.

Notes

[1] J. Ross Dancy, The Myth of the Press Gang: Volunteers, Impressment, and the Naval Manpower Problem in the Late Eighteenth Century (Woodbridge: Boydell, 2015), 5, 8. A smaller database and the book’s final chapter address the Quota Acts experiment.

[2] Dancy, Myth, 187.

[3] N.A.M. Rodger, “Introduction,” Quintin Colville and James Davey, eds., Nelson, Navy, Nation: The Royal Navy and the British People, 1688-1815 (London: National Maritime Museum, 2013).

[4] Dancy, Myth, 132.

[5] Dancy, Myth, 9.

[6] Dancy, Myth, 66.

[7] “Social friction” is Dancy’s preferred term; it appears at least three times: Myth, 109, 118, 189.

[8] Dancy, Myth, 140.

[9] Dancy, Myth, 54; see also 63 and 187.

[10] Dancy, Myth, 152, 140.

[11] Many of Dancy’s statements about the opposition’s historiography are a little challenging to follow because they do not come with named historians, footnotes, or direct quotations. See for example Dancy, Myth, 114, 120, 133.

[12] Dancy, Myth, 66.

[13] Dancy, Myth, 54.

[14] Dancy, Myth, 39.

[15] Dancy, Myth, 63.

[16] Dancy, Myth, 117.

[17] Dancy, Myth, 66.

[18] Dancy, Myth, 67.

[19] Dancy, Myth, 67-68.

[20] Isaac Land, War, Nationalism, and the British Sailor, 1750-1850 (New York: Palgrave Macmillian, 2009), 86.

[21] Philo Nauticus, “A proposal for the encouragement of seamen,” in J.S. Bromley, ed. The Manning of the Royal Navy: Selected Public Pamphlets, 1693-1873 (London: Navy Records Society, 1974), 104-113 , quoted page 109.

[22] John Knox, Observations on the Northern Fisheries (London, 1786), 3, 6.

[23] Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, s.v. John Knox, Thomas Telford.

[24] Eric Hobsbawm and Terence Ranger, eds., The Invention of Tradition (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1983).

[25] Philo Nauticus, “A proposal for the encouragement of seamen,” in Bromley, ed., 104-113 ; the speech by Luttrell is referenced in Charles Butler, On the legality of impressing seamen, 2d ed, with additions “partly by Lord Sandwich” [1778] as reprinted in The Pamphleteer XXIII (1824), page 6; TNA HO/28/9, 30 January 1793, Peter Rothe at Newcastle to P. Stephens (attached documents); Independent Whig, 4 August, 18 August, 22 September, 29 September, 6 October, 18 October, 3 November 1816; Edinburgh Review, (October 1824), 154-181.

[26] TNA HO 28/29, sworn deposition attached to 4 May 1803, Adam Mckenzie to Evan Nepean.

[27] Isaac Land, “Domesticating the Empire: Culture, Masculinity, and Empire in Britain, 1770-1820,” Ph.D. dissertation (University of Michigan, 1999), 77.

[28] TNA HO 28/23, 4 October 1797, Captain J. Brenton at Leith to Evan Nepean.

[29] TNA HO 28/9, 30 January 1793, Peter Rothe to P. Stephens.

[30] TNA HO 28/37, f203 (from Liverpool, 1810).

[31] TNA HO 28/13, 13 November 1793 (attachment to 29 November letter from Stephens to Dundas).

[32] TNA HO 28/24, 16 September 1798.

[33] TNA HO 28/40, 15 August 1811; Land, War, 2.

[34] TNA HO 28/7, 20 July 1790, R. Dawson to Grenville; HO 28/24, 11 July 1798, Evan Nepean to John King; HO 28/34, 1 September 1807, John Barrow to J. Beckett; HO 28/40, 21 August 1811, John Barrow to J. Beckett.

[35] Scottish National Dictionary, s.v. “Press gang.”

[36] Aviva Ben-Ur, “Purim in the Public Eye: Leisure, Violence, and Cultural Convergence in the Dutch Atlantic,” Jewish Social Studies: History, Culture, Society n.s. 20, no. 1 (Fall 2013), 32-76, see page 55.

[37] Brunsman, Evil, 82; see also Rogers, Press, 10: parish archives also show cases of men taken inappropriately.

[38] Brunsman, Evil, 6; Rogers, Press, 5.

[39] Brunsman, Evil, 188.

[40] Brunsman, Evil, 6.

[41] N.A.M. Rodger, The Command of the Ocean: A Naval History of Britain, 1649-1815 (New York: W. W. Norton, 2004), 500.

[42] Dancy, Myth, 106-108 does offer his thoughts on this problem. Others will, I’m sure, delve deeper; I think the evidence he discusses is amenable to more than one interpretation.

[43] Brunsman, Evil, 246.

[44] Rodger, Command, Appendix VI.

[45] Paul A. Gilje, “Free Trade and Sailors’ Rights: The Rhetoric of the War of 1812,” Journal of the Early Republic 30, no. 1 (Spring 2010), 1-23, quoted pages 11-12. See also Brunsman, Evil, 247, whose version is about 10,000 U.S. citizens pressed between 1793 and 1812. Rodger, Command, 566 refers to a figure of 6,500 U.S. citizens as the “result of modern research,” from a diplomatic history by Bradford Perkins published in 1961.

[46] Rogers, Press, 118.

[47] Butler, Legality.

[48] Rogers, Press, 69-71, 85, 96-97.

[49] Brunsman, Evil, 177.

[50] Brunsman, Evil, 181.

[51] Brunsman, Evil, 148.

[52] Brunsman, Evil, 30-31.

[53] Dancy, Myth, 188.

[54] Land, War, 105-130; Isaac Land, “Patriotic Complaints: Sailors Performing Petition in Early Nineteenth-Century Britain,” in Writing the Empire: Interventions from Below, Fiona Paisley and Kirsty Reid, eds. (London: Routledge, 2013), 102-120.

[55] I’m so pleased that there is now a biography of Trotter: Brian Vale and Griffith Edwards, Physician to the Fleet: The Life and Times of Thomas Trotter, 1760-1832 (Woodbridge: Boydell, 2011); see also Isaac Land, “Prisoners of Habit: Slave Ships, Naval Medicine, and Thomas Trotter’s Theory of Alcoholism,” Trafalgar Chronicle 24 (2014), 115-127.

[56] Trotter, Medicina Nautica: An Essay on the Diseases of Seamen (London, 1797), 46.

[57] Trotter, A Practicable Plan for Manning the Royal Navy and Preserving our Maritime Ascendancy, without Impressment (Newcastle: Longman, 1819), 40.

[58] Trotter, Medicina Nautica, 44.

[59] Dancy, Myth, 154.

[60] Adam Zamoyski, Phantom Terror: Political Paranoia and the Creation of the Modern State, 1789-1848 (New York: Basic Books, 2015) , 55.

[61] Trotter, Medicina Nautica, 44. Trotter relates that he completed this manuscript toward the close of 1796.

[62] Trotter, Practicable Plan, 34.

[63] Gilje, “Free Trade and Sailors’ Rights,” 15-16.

[64] For comparison, bear in mind that some of the newer scholarship on the antislavery movement makes removing blots from Britain’s escutcheon the foremost driving factor: Christopher Leslie Brown, Moral Capital: Foundations of British Abolitionism (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2006).

A fascinating piece, and something I can claim no expertise in.

However, I wonder whether there is an issue here that goes far deeper. As you say, assuming that we can trust data recorded, even when officially done so, is a dangerous game. I wonder if we are in danger of falling for this, seduced by the opportunities offered by improvements of computer processing. It strikes me that this may take us back to previous eras of history, over reliant on official statistics, economics, etc., and blind to the nuances of individual circumstance and historical actors.

As you quite rightly state, the pride, opinions, incompetence or even laziness of individuals could skew our understanding of the figures. It seems dangerous to reduce vastly difference events and circumstances to a number on a page.

Whilst undoubtedly these projects that utilise huge amounts of data can open our eyes to wider patterns, there clearly needs to be a level of understanding that they do not replace other sources, and are fairly useless without them. All they tell us is what is officially recorded, not what happened.

I think one problem with studies of press gangs is that it takes place in isolation from to what happened earlier in the Seventeenth Century, mainly because the early muster lists don’t provide the information that is available for the mid eighteenth century navy. However it is possible to find examples in the 1690 of gangs rescuing pressed men from the press as at Hertfordshire. There are a series of accounts for press tenders 1702 – 1715 which give the names of the people and the areas where they were seized which can be found in the TNA Adm 106 miscellany series.

The other problem is that impressment warrants were also issued by the Navy board to ensure that the navy had a regular supply of men to build the ships. This happened at Chatham in 1678 at the beginning of the Thirty New Ships building programme. Intimidation also took place and in the end the Navy Board had to move their representative and his family to Woolwich as they were being threatened. In some cases too teh men were taking the impress money and not turning up.

Thank you for the review, although I fear we will have to agree to disagree on many of these points.