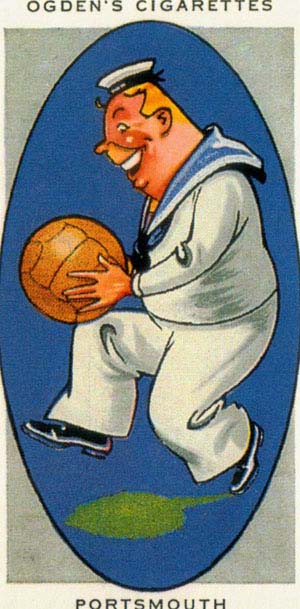

Ogden’s Cigarette Card, Portsmouth F.C.

The role of class, gender and place identity formation through the support of the local football team has been explored by a number of historians.[1] Through local rivalries and the celebration of civic pride football supporters were able to make sense of their urban environment and their place in the world.[2] Portsmouth’s ‘Pompey Chimes’ chant resonated to the tune of the town hall bells, which further underlined the symbiosis of football and civic patriotism. [3] Indeed, the localised persona of a team came to symbolise those who supported it.[4] In an article in The Strand Magazine, ex-Portsmouth Football Club player C. B. Fry described the club:

He is heavily supported by soldiers from the forts and barracks, by sailors from the battleships and other crafts, and by dock hands of various grades … Pompey as a team is more of a sailor than anything else, rollicking, good-natured, dare-devil fellow, moving with free limbs and a hearty roll.[5]

It is evident that looking at reports of Portsmouth Football Club’s fixtures during the Edwardian era, which were mainly in the Southern League, rivalries were keenest amongst neighbouring port towns and those with similar industries, such as the other Royal Dockyard towns of Plymouth and Chatham. Local rivalry was quickly stirred up in the provincial press for the first local derby match against Southampton. The Hampshire Telegraph roused its readership by framing the match in terms of historic precedent both on and off the pitch:

The first of what, it is hoped, will be a long series of historic football battles between Portsmouth and Southampton took place today at Fratton Park … There has always been a deal of rivalry between the two towns, but Southampton long since took the initiative in securing the services of a good professional team. Last season when the Royal Artillery met the Saints in the Southern League there was a considerable amount of interest evinced, and now that Portsmouth can also boast of its own professional eleven that interest has vastly increased.[6]

Similarly for Brighton it was reported that “Such keen rivalry exists … a good gate for the match was practically assured.”[7] Rivalries with the other Royal Dockyard towns were similarly conceived. For Portsmouth’s first fixture with Chatham it was written:

The rivalry was further fueled during the analysis when the paper criticised Chatham for their reputation of “rough play” and praised Portsmouth for being the superior team on the day. One match with Plymouth in 1906 broke attendance records for a home game at the club and the local newspaper reported that “the utmost interest is being evinced in the meeting of the two Dockyard towns.”[9]

Indeed, it is evident that the role of popular sport, the press and civic pride helped to bolster an image of port towns in the imagination of their citizens, which may be something to explore further.

References

[1] Richard Holt, Sport and the British. A Modern History, (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1989), 169-174; D. Russell, Football and the English. A Social History of Association Football in England, 1863-1995, (Preston: Carnegie Publishing Ltd, 1997), 64-69; Brad Beaven, Leisure, Citizenship and Working-class Men in Britain, 1850-1945, (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2005), 72-81.

[2] Holt, Sport and the British, 172.

[3] C. B. Fry, “Football Teams Recalled”, The Strand Magazine, October 1903, 366-377.

[4] Holt, Sport and the British; 173.

[5]Fry, “Football Teams Recalled”, 366.

[6] Hampshire Telegraph, September 7 1899.

[7] Portsmouth Evening News, September 1 1912.

[8] Hampshire Telegraph, September 9 1899.

[9] Portsmouth Evening News, August 28 1906 and September 1 1906.

Comments are closed.