Pirates have many names—freebooters, brethren of the coast, members of the company, buccaneers. Throughout the late seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries, thousands of pirates stalked the seas, attacking merchant vessels trading in the West Indies, West Africa, and North America. This period of violence and thievery has been well documented and immortalized as the ‘Golden Age of Piracy.’ Even though it has been more than three hundred years since pirates walked the docks of Atlantic seaports, cleaned their vessels in hidden island alcoves, and hoisted their dreaded black flags, these men continue to capture our imagination. Books, novels, plays and movies keep the pirate mythology alive and well in popular culture. But these mediums often present at best a one-dimensional picture, and at worst, a completely inaccurate one of the lives and loves of history’s most notorious scoundrels. In the words of the French historian Hubert Deschamps pirates were:

… a unique race, born of the sea and of a brutal dream, a free people, detached from other human societies and from the future, without children and without old people, without homes and without cemeteries, without hope but not with- out audacity, a people for whom atrocity was a career choice and death a certitude of the day after tomorrow.

Though there certainly is some truth in this characterisation, it is a gross over-generalisation. Many of these depictions and our understanding of the nature of the pirate are wrong. There are troves of evidence proving that a not insignificant number of these men were married, had strong family ties and connections to a community on land, were educated (at least to some extent) and came from families who enjoyed some degree of status in their respective societies.

In my new historical non-fiction book, The Pirate Next Door: The Untold Story of Eighteenth Century Pirates’ Wives, Families and Communities, I delve into the inner lives of pirates, their faiths, communal ties, and great loves. You’ll hear about the wives, families, and communities of four pirate captains from the Golden Age who were active from 1695–1720. One of the most remarkable things my research has revealed is the role women played in the lives of pirates—a much larger one than has been acknowledged in previous pirate literature. And you will see that behind many a pirate was a strong woman on land.

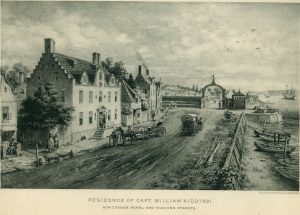

Though pirates were active up and down the eastern seaboard of the United States and Caribbean, I’ve chosen to focus specifically on four pirates who operated in New England. This area was a hub of pirate activity, and I chose these four pirates in particular because they were all married (except Captain Samuel Bellamy who had an ‘intended’), all interacted with each other at some point or another, and because all of them were involved— in some cases, quite actively involved—in the larger land-based community. These men are Samuel Bellamy of Cape Cod, Massachusetts, Paulsgrave Williams of Block Island, Rhode Island, William Kidd of New York and Samuel Burgess of New York.

While I focus on these four men, my research included the lives of eighty married pirates. Their stories help craft a picture of the wider world of pirates and the surprising sense of community these men often shared, inspiring us to take another look at the conventional image of pirate life.

I have reconstructed the lives of the four pirate captains from historical facts recorded in archived criminal cases, depositions of captured pirates and witnesses, memoirs of pirate captives, reports from colonial governors, Last Wills and Testaments, land transactions, town clerk records, newspapers, vital records (including birth, marriage and death certificates), dying words, and, in one instance, a prenuptial agreement. I also used correspondence that was found in a sea chest in Captain Samuel Burgess’ pirate ship the Margaret when it was captured by a British privateer in 1699. Among the over two hundred documents in the sea chest were several letters from the pirates to their wives and families, and letters from wives and families to the pirates. The sheer existence of the letters dispels the notion that pirates were illiterate social isolates estranged from land-based society. The letters show that correspondence was conducted tens of thousands of miles across the globe between Indian Ocean pirates and North American colonists and that there was successful and direct communication between New York and Madagascar and back again. These documents, called “prize papers” are in the Admiralty Papers in the National Archives in London.

Pirates have been misrepresented for centuries and portrayed as less than human. The sea created a geographic boundary that separated the pirate from the traditional social institutions on land such as work, church and family, but pirate communities had a highly organised social structure designed to support and maintain their relationships on land while they were at sea. Pirates lived in their own civil society that cared for and protected their own as well as others. Quite often a pirate travelled thousands of miles to return the personal belongings and booty of a deceased pirate to his wife or relations. Pirates had a mail system that allowed them to keep in contact with family members back home. The pirates’ ‘post office’ was under a large rock with a hole in it located near where the ships came in on Ascension Island, a small remote island in the South Atlantic. New York merchant captains trading with the pirates in Madagascar dropped off and picked up the pirates’ mail on Ascension Island on a regular basis. They also had an established program for retiring pirates—if a pirate paid 100 pieces of eight to the captain and supplied his own food and drink for the voyage, he could catch a ride on the next available ship from Madagascar to New York and return to society.

Considering these men through the lens of their relationships to their wives, families, and communities brings out an understanding of pirates that has not been previously considered and it shows that the pirates were not so-called ‘enemies of the human race.’ Rather, they were human beings, like us, who sought to live their lives under challenging circumstances as they attempted to meet their own needs but also those of their families and communities.

Comments are closed.