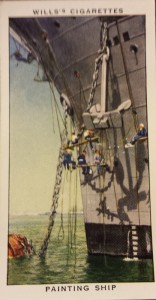

It is an interesting question whether or not the men who joined the Royal Navy in the late nineteenth century knew of or imagined the time-consuming and monotonous aspects the job entailed. Consideration of sailor diaries reveals that one of the most common, and indeed, disliked tasks aboard ship, was painting the vessel, inside and out.[1] It is therefore interesting that many sailors chose to write so often about it. Whilst diaries can be brief accounts of life in the service – some only listing the daily routine – occasionally sailors chose to be more verbose and reveal their thoughts on this subject. This article seeks to briefly introduce this aspect of sailor life and demonstrate the usefulness of sailor diaries as an historical source.

As warships dramatically increased in size painting became a long and laborious task lasting many weeks.[2] This was further exacerbated by the ready adoption of coal as fuel for the boilers which greatly increased the task of keeping the ship clean.[3] As Alfred East dryly remarked, “steaming at 15 knots and saying goodbye to a clean ship”.[4] Similarly, J. Dicks commented on the pressure put upon crews to keep vessels shipshape. On sighting the Admiral’s flagship as his ship prepared to re-join the fleet:

Likewise A. C. East records an outbreak of ‘Kingitis’ amongst the officers aboard HMS Natal when they hear the King is planning an inspection.[6] Robert Percival, a socialist-minded stoker, remarks with some condemnation that “paint was used in the most reckless fashion to hide blistered funnels” and make ships presentable.[7] This was not such a rare occurrence as James Colville, a young midshipman, described “our funnels began to peel… they weren’t very grand when we started and during the trial the paint simply flaked off.”[8]

Sailors’ thoughts on the subject reflect similar views. Occasionally it could be a chance to have a joke with friends, and sometimes the odd accident was cause for amusement. Take for example an account by Seaman William Williams who described, with some amusement, an accident involving a bucket of paint being pitched over an officer’s head and cap.[9] At first it appeared to many men an easy task as shown by Edwin Fletcher based at HMS Excellent, the Gunnery School. He began painting on 28th May recording: “whitewashing – it’s a quiet number.”[10] However by 1st July he has noticeably hardened to the task: “I have still got to “carry on” with the whitewashing party.”[11]

This article has given a brief introduction to a common task set before sailors aboard ship. Painting was an arduous and unpleasant job but one that sailors approached in their own way. Gentle grumbling was the norm as well as a dry attitude that can be glimpsed from the way in which they recorded their thoughts. More importantly it is hoped that this article shows the insight sailor diaries can give into the life of those who served. Serving in the Royal Navy was not all glamour, adventure and the exotic; ‘painting for empire’ was a mundane but essential part of naval life, especially as the navy grew in the public sphere and increasingly became a cultural symbol.[12]

References

[1] The most unpleasant task aboard ship at this time was undisputedly coaling. For more on this subject see Henry Baynham, Men from the Dreadnoughts, (London: Hutchinson & Co, 1976), 164-171 and Christopher McKee, Sober Men and True: Sailor Lives in the Royal Navy 1900-1945, (London: Harvard University Press, 2002), 119-125.

[2] See RNM, 1980/115/2: Diary of Edwin Fletcher; RNM, 1965 65/76: Diary of William Williams.

[3] McKee, Sober Men, 120-121.

[4] RNM, 1990/95: Diary of Alfred East.

[5] RNM, 1979/100: Diary of J. Dicks.

[6] RNM: 1995/90: Diary of A. C. East.

[7] RNM, 1988/294: Memoirs of Robert Percival; See also Jan Rüger, The Great Naval Game: Britain and Germany in the age of empire, (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2009), 123.

[8] RNM, 1997/43/1: Diary of James Colville.

[9] RNM, 1965 65/76: Diary of William Williams.

[10] RNM, 1980/115/2: Diary of Edwin Fletcher.

[11] RNM, 1980/115/2: Diary of Edwin Fletcher.

Comments are closed.