Residents of the island of Nantucket played a significant and prominent role in the development and control of much of the global whaling industry during the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. This narrative has dominated the history of this small New England island. Less researched, however, is an event that for a brief period of time threatened to disrupt or even eliminate Nantucket’s whaling industry and expose the island’s connection to, and total dependence on, the sea for its very existence. Moreover, it highlights how coastal – and especially island – communities and their industries have historically been prey to the consequences of wider national and international politics. Indeed, the actions of the residents highlight the agency they had in negotiating settlements for their survival.

In late August 1814, at the height of the War of 1812 and in the midst of the Royal Navy’s blockade of America’s Eastern Seaboard, acting out of desperation, the small Massachusetts Island of Nantucket took matters into its own hands. Without consent from the Federal Government or the Commonwealth of Massachusetts, representatives from the Island entered into negotiations with the Royal Navy. These negotiations would eventually lead, late in the war, to a neutrality agreement between Nantucket and Great Britain.

Tired of the unnecessary war with America and weary from the long, just ended wars with France, in early 1814 Parliament ordered the Royal Navy to escalate the war at sea.[1] Responding to War Secretary Bathurst’s orders and his desire “make mercantile centers of New England feel the pressure of war,” [2] Vice Admiral Alexander Cochrane, Commander-in-Chief of the North Atlantic Station, issued a proclamation in April 1814 extending the Royal Navy’s existing blockade of the mid-Atlantic region to immediately include New England.[3] The blockade straightaway impacted the Island of Nantucket disproportionately harder than the mainland. It effectively isolated the Island it by shuttering its dominant employment and wealth generating industry (whaling), while cutting it off from the New England mainland from which it imported virtually all of its food and fuel. Nantucket had historically been wholly dependent on access to the sea for its survival and prosperity. Its whaling ships supplied a significant portion of whale oil and related products to Europe and the Americas for decades, generating a significant source of wealth for the Islanders.[4]

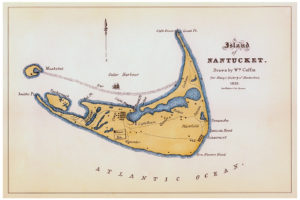

Illustration by William Coffin in Obed Macy, A History of Nantucket (Boston: Hillard, Gray, 1835), iv.

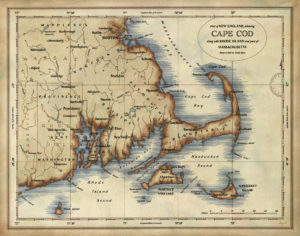

Blockading Nantucket proved to be relatively easy assignment for the Royal Navy. Small in size (forty-eight square miles), and thirty miles from mainland Cape Cod, Nantucket was already geographically isolated. Surrounded by shallow waters and shifting sandbars and having only one, narrow, navigable channel leading to the Island’s only harbor made it easy for a small blockading force of warships or privateers to shut things down. The ease of maintaining the blockade was demonstrated in late June, 1814 when a single tender (containing one gun and twelve sailors) from the frigate HMS Nymphe blocked entrance to the Island’s only harbor, making any access to and from the harbor impossible.[5] Noted Nantucket resident and historian Edouard Stackpole wrote “the Island’s whaling fleet and coastal vessels bringing supplies from the mainland were easy prey for a host of privateers and British cruisers.” [6]

Without much sympathy nor support from the Federal or State government, the Islanders chose to act on their own. On 22 July 1814, a petition signed by Nantucket residents was sent directly to Vice Admiral Cochrane seeking relief from the blockade. The appeal was based on humanitarian reasons, explaining the Island’s isolation, its lack of natural resources, and the opposition by its dominant religious group, the Quakers, to the war.[7] This must have struck a chord with Cochrane, as he directed one of his top commanders, Rear Admiral Henry Hotham, to investigate. If the claims were found to be true, Hotham was empowered by Cochrane to issue passports allowing them to import necessary provisions. On 23 August, 1814, a proposal from Hotham was delivered to the Island under a flag of truce. If Nantucketers were to declare themselves “absolutely neutral” in the war, deliver up any military stores held on the island, and provide any surplus supplies to British ships, a specified number of vessels would be permitted to import wood, provisions and other needed supplies.[8] A town meeting was held that same night and Nantucket officially agreed to terms of Rear Admiral Hotham’s neutrality offering.[9]

The neutrality agreement provided a degree of relief. A limited number of safe passage passports allowed Nantucket boats to obtain provisions from the mainland, which alleviated some shortages of food and fuel. However, the key area which the Nantucketers sought relief, freedom to resume whaling, was met with a resounding rejection from Cochrane. Since the neutrality agreement happened so late in the war and a peace treaty was signed a few months later (December 24, 1814), the full repercussions of the agreement and how it would have withstood the delicate political balance the Islanders had placed themselves, the United States Government and Great Britain became a moot issue.

In the course of research for my dissertation, which focused on the War of 1812 and Vice Admiral Cochrane’s command decisions late in the war, I was struck by how little academic attention was written pertaining to Nantucket’s neutrality efforts. When the topic is mentioned in some writings, it is buried in the more significant, larger context of the war. Even with the recent plethora of publications surrounding the 200th anniversary of the war, most publications at best devote a page, paragraph or footnote to the event. A deeper dive into the why it happened rather than a reporting of what happened is warranted.

Another interesting aspect of this event is that Nantucket took this drastic initiative without consent of the Federal Government or the Commonwealth of Massachusetts, which it is a part of. While the Islanders tried making their case for assistance from the Madison Administration and the State, no help was forthcoming. Further research would be of value that examined if the Federal and State governments simply ignored the Islanders plight, turned other eye, or were they just too powerless to help the Islanders.

Finally, further research is needed to ascertain Cochrane’s true intentions in offering neutrality to Nantucket. Some historians have suggested it was his way of embarrassing the Madison Administration. Others have suggested he wanted to coax the skilled Nantucket whalers to move their whaling operations to British territories. Or perhaps it was just a humane gesture from someone who many historians considered a cold and calculating man?

This short piece intends to shine a light and inspire further research on a unique, brief period of time in which Nantucket’s residents, stuck in the middle of a war many of them did not support, took desperate measures in order to survive and keep a connection to the sea for its very existence.

Notes:

A note of thanks to the research staff at the Nantucket Historical Association’s Research Library (www.nha.org) for their interest and assistance with this interesting, unique period of Nantucket’s history). Special thanks also to artist, calligrapher and cartographer Daniel Reeve (www.danielreeve.co.nz) for graciously granting permission to use his classic illustration of Cape Cod and the Islands.

[1] Barry J. Lohnes, “British Naval Problems at Halifax During the War of 1812,” The Mariner’s Mirror, 59:3 (1973): 317-333.

[2] Letter from Bathurst to Sherbrooke, 6 June 1814, Public Archives of Nova Scotia, vol. 62, doc. 120; Lohnes, “British Naval Problems,” 327.

[3] Letter from Vice Admiral Sir Alexander Cochrane to John W. Croker, 28 April 1814, The National Archives (hereinafter TNA), ADM 1/506; Lohnes, “British Naval Problems,” 327; Newhampshire Sentinel, 1 May 1814, 1; Goldenberg, “Notes, Bibliographies, and Documents,” 429.

[4] Reginald Horsman, “Nantucket’s Peace Treaty with England in 1814,” The New England Quarterly, 54:2 (1981): 180-198.

[5] Horseman, “Nantucket’s Peace Treaty,” 186.

[6] Edouard A. Stackpole, An Incident During The War of 1812, Nantucket Historical Association Research Library, War of 1812 files, blue file.

[7] Letter from Inhabitants of Nantucket to Cochrane, 22 July 1814 TNA, ADM 1/507/260-61.

[8] Letter from Cochrane to Croker, 5 October 1814 TNA, ADM 1/507/249-51.

[9] Town Meeting, 23 August 1814, Town and County of Nantucket Archives; Letter from Hotham to Cochrane, 29 August 1814 TNA, ADM 1/507/252-55, 258). Hotham wrote to Cochrane notifying him of Nantucket’s neutrality agreement and his issuing a circular ordering ships of the Royal Navy and privateers to honor the passports he had issued.

Comments are closed.