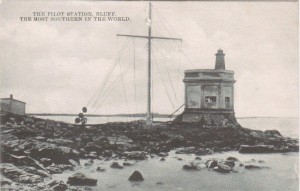

So reads a famous signpost at the port town of Bluff, which is located on the south coast of New Zealand’s South Island. With little between it and the Roaring Forties, Bluff was indeed “one of the farthest corners of the British Empire.”

So reads a famous signpost at the port town of Bluff, which is located on the south coast of New Zealand’s South Island. With little between it and the Roaring Forties, Bluff was indeed “one of the farthest corners of the British Empire.”

A key inlet for British migrants from the 1860s and a key outlet for frozen meat when New Zealand was “Britain’s farm”, the port of Bluff is currently the focus of a three-year research project being undertaken by Dr. Michael J. Stevens, a lecturer in the Department of History and Art History at the University of Otago at nearby Dunedin. A “Bluffie” himself, Stevens thinks that his project—“Between Local and Global: A World History of Bluff”—has the potential to reshape thinking about New Zealand’s economic development and race relations.

Southern New Zealand was pulled into the expanding New South Wales frontier from the 1790s and was firmly embedded in it by the 1820s. This was on account of sealing, whaling, and flax-trading, which brought visiting European and American sailors into a suite of intimate relationships with Māori groups dotted on both sides of what became known as Foveaux Strait. This included interracial marriage, which occurred earlier and more intensively in southern New Zealand than many other parts of the country. Stevens, for instance, is one of many contemporary southern Māori descended from nineteenth century unions of Māori women and whalers: in his case a high-ranking woman and her Bristol-born husband who landed in the region in 1836 and remained there until his death in 1906.

Bluff was a key site of cultural encounter prior to New Zealand’s formal incorporation into the British Empire in 1840 and in the decades that followed, as its strategic importance as a deep-water port was realised, it retained and drew in a number of Māori families. Accordingly, in the 2006 national census, while 15% of all New Zealanders self-identified as Māori, as did 11.8% of Southland residents (which includes Bluff), the figure for Bluff alone was 43%.

In 1956 the port was therefore described as an “Outpost of Maoritanga”. This article observed that, “Fishing plays an important part in the activities of these people due to the proximity of the town to the sea” and noted that a major harbour development project about to begin would provide stable employment that would attract further Māori to Bluff.

A visit to Bluff in 1887 by a prominent Bostonian had earlier produced similar comments. The writer and publisher Maturin M. Ballou described the town, then officially known as Campbelltown, as “a pretty little fishing village of some sixty houses, with a population of less than a thousand” and explained that “These people gain their living mostly from the neighboring sea, and from such labor as is consequent upon the occasional arrival of steamships on their way to the north.” He also recorded that “Many half-caste people were observed, born of intermarriage between Europeans and the aborigines [i.e. Māori]” the male portion of whom were “said to make excellent and intelligent seamen.”

The English novelist, Anthony Trollope, who landed at Bluff 15 years earlier than Ballou, took quite a different view and recalled that when he disembarked from his ship and “asked to be shown some Maoris” he was told that “they were very scarce in that part of the country.” He continued: “Indeed, I did not see one in the whole province, and it seemed as though I might as well asked for a moa [a famous but extinct species of bird]”.

Had he arrived at Bluff in February rather than August, Trollope would have observed immense numbers of inflated blades of bull kelp drying in the sun on verandahs and clotheslines belonging to Māori people. Fully manufactured, these so-called kelp bags were used to store preserved juvenile “muttonbirds” (sooty shearwaters). These seabirds are exclusively harvested by southern Māori from islands south of Bluff and are a staple foodstuff in Bluff households. As late as 1937 these kelp bags indicated Māori dwellings in the port, which were otherwise little different from those of non-Māori residents. This could be true of the people themselves. “Maoris”, wrote the reporter Dorothy Wiseman, “are plentiful in Bluff, though there are few of them now who do not show some admixture of pakeha [white] blood.”

New Zealand history, including Māori history, has a strong terrestrial bias and Stevens’ project is part of an effort to give the sea and coastal settings, and the people who live and work in them, greater prominence.

In addition, while most Māori history produced over the last 30 years has occurred as part of restitution for acts and omissions on the part of the Crown that materially disadvantaged Māori kin-groups, the project aims to shed light on New Zealand’s incorporation into an expanding capitalist world economic system and the ways in which this—as well as colonial governments—impacted upon Māori, both negatively and positively. Māori disempowerment was widespread and wide-ranging during the colonial encounter, but it was also uneven, and nowhere was it absolute. Put differently, the project seeks to test the idea that Bluff-based Māori were not just victims of the British Empire, but also participants in it.

Further information on the project is available here: http://www.worldhistoryofbluff.org.nz/

Comments are closed.