My book, Dockworker Power: Race and Activism in Durban and the San Francisco Bay Area, hopefully will be of interest to readers of the Port Towns & Urban Cultures blog. The title proclaims its basic thesis. Though many folks are unaware of it, including a surprising number of labor and maritime historians, the very term used for workers’ most powerful weapon has maritime origins! In 1768, as historians Peter Linebaugh and Marcus Rediker recalled, sailors “struck (i.e. took down) the sails of their vessels, crippling the commerce of the empire’s leading city [London] and adding the strike to the armory of resistance.”[i]

Since the ship must sail on time, dockers know that stopping work at a strategic moment has tremendous potential. Or as Lou Goldblatt, a long-time leader of the union representing dockers on the US West Coast, explained: “The shipping industry has a feature that should never be underestimated—the economic power of the longshoremen [the typical term in the US for dockers] is fantastic compared to most workers; the amount of economic leverage they have.” Though most people might not appreciate this reality, employers are not among them.[ii]

My book does not primarily focus on how workers help themselves by unionizing—though they did and do. Rather, I explore how workers, when collectively organized, use their power to agitate for racial equality in their own societies and even other countries. In Durban and the San Francisco Bay Area, dockworkers drew on longstanding radical traditions to fight against apartheid in South Africa and for civil rights in the United States. They also demonstrated a deep commitment to black internationalism and leftist politics via repeated work stoppages to protest racism and authoritarianism in other countries, i.e. transnationally. The book’s third main theme examines how dockers persevered when a revolutionary new technology—containerization—sent a shockwave of layoffs through the industry as it drastically changed the entire global economy.

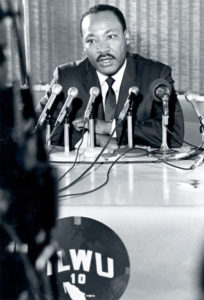

When discussing my work to ordinary humans—the 99.999% who are not paid to be historians—I try to explain why a seemingly obscure subject is relevant: in particular, how a port and its connection to the wider world explains so much about these cities. For instance, many who live in the San Francisco Bay Area (or are familiar with it), fail to appreciate that the Beats were shaped by the port and its workers. Why did Lawrence Ferlinghetti open up City Lights Bookstore in San Francisco’s North Beach neighborhood and why did his fellow Beatniks make North Beach their home? Well, it was a place where many dockworkers, sailors, and other workers in the shipping industry lived. As a result, it had become quite cosmopolitan and tolerant of people with diverse backgrounds, ethnicities, and beliefs. And it was affordable (truly a shock in SF today). It’s still where the dispatch hall of SF Bay Area dockworkers, proud members of Local 10 of the International Longshore & Warehouse Union, stands. Local 10’s hall also was where the very first Trips Festival—think the Grateful Dead performing to a crowd of a thousand hippies on acid—happened in 1966. And it was the place where Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. was made an honorary member of ILWU Local 10, following in the footsteps of another great African American activist and radical, Paul Robeson. All of these convergences (and many others detailed in my book) are not merely coincidences.

Martin Luther King, Jr. speaking at ILWU Local 10’s hall in San Francisco, 1967. Image courtesy of ILWU Archives

Similarly, many in South Africa don’t appreciate the vital role of Durban dockers to the long struggle against apartheid—a nasty combination of white supremacy and fascism. Those who loaded and unloaded ships in what remains sub-Saharan Africa’s busiest port consisted entirely of black men, mostly Zulus along with some Pondos. Due to centuries of racial oppression and imperialism, they (and most other black South Africans) were desperately poor. However, like dockworkers in ports across the seven seas, their work inculcated a collective identity that regularly turned into collective action—despite a white minority regime that prohibited black workers from unionizing or striking. Nevertheless, they used their “casual” status quite cleverly and organized “stay-aways” that were strikes in everything but name. They did so to increase their poverty wages but also, in the late 1950s, in coordination with the African National Congress, the country’s largest anti-apartheid organization. Fast forward to 1969 and early 1970s, when ferocious repression, nationwide, had created a “quite decade” for the apartheid regime. Though nearly every other effort to resist had failed, dockers struck several times—including just a few months prior to the legendary Durban Strikes of 1973 that relaunched the wider struggle. Steve Biko, the father of Black Consciousness, also resided in Durban at that time as did Professor Rick Turner, who inspired some radical white students at the University of Natal, Durban, to join the struggle. This “Durban Moment” set the stage for black student protests that broke out in Soweto in 1976. Yet, today, many South Africans remain unaware of the centrality of the port and its workers to the struggle against apartheid.

Using comparative, transnational, and global labor historical methods, Dockworker Power brings to light surprising parallels in the experiences of dockers half a world away from each other. It’s the first comparative history of dockers in Global North and Global South ports and among the first spanning the traditional and container eras. Historically, dockworkers have been able to change their conditions and promote social justice causes around the world. Notably, they continue to operate at a strategic choke point of the global supply chain, and they still appreciate their importance despite being largely invisible to the wider public.

I would like to invite readers in England to attend one of my book talks:

14 May 2019: Hosted by Organisation and Employment Relations Research Centre, University of Sheffield

15 May 2019: Hosted by American Studies and History, University of East Anglia.

16 May 2019: Hosted by Centre on Labour and Global Production, Queen Mary University of London.

[i] Peter Linebaugh and Marcus Rediker, The Many Headed-Hydra: Sailors, Slaves, Commoners and the Hidden History of the Revolutionary Atlantic (Boston: Beacon, 2000), p. 219.

[ii] “Louis Goldblatt: Working Class Leader in the ILWU, 1935-1977,” with an Introduction by Clark Kerr, Interview conducted by Estolv Ward, 2 vols (Regional Oral History Office, The Bancroft Library, University of California, Berkeley, 1978-1979), p. 866.

We enjoyed your article so much! We like how a author explained the concepts.

I think that is definitely as good as the write-up of these guys https://ideenkicker.ch/pathfinder-wrath-of-the-righteous/. Thank a person so

much just for this article, I may wait for your following

publications.