The practice of gibbeting, also known more specifically as hanging in irons, or hanging in chains, was a particularly macabre punishment for a variety of convicted felons, and yet it is the image of the pirate cadaver swinging eerily in the breeze, which appears to have become most engrained in popular culture since the eighteenth century. The practice was only formerly recognised as one of two mandatory punishments for executed criminals in the 1751-52 “Murder Act”.[1] Considering that a great many crimes carried the death penalty at this time, by not allowing the murderer a proper burial the Murder Act enabled a way for the more heinous offences such as murder, piracy and smuggling, to be differentiated from seemingly less grievous crimes.[2] Gibbeting continued throughout the eighteenth century but the practice was finally ended in 1832; gibbet posts, however, remained “a significant part of the English landscape” during the early nineteenth century with the last post being demolished around 1856.[3]

Albert Hartshorne, whose book Hanging in Chains stands out as a key contemporary text on Victorian gibbet lore states that the word ‘gibbet’ was often conflated with ‘gallows’.[4] The act of gibbeting itself could imply simply suspending a corpse from a post, or exhibition of the corpse in a gibbet cage or “suit” which, though extremely expensive and time consuming to make served to increase the horror experienced by the observer.[5] Hartshorne notes that gibbeted bodies displayed in more remote regions were specifically avoided after nightfall; that “belated wayfarers were grieved by the horrid grating sound as the body in the iron frame swung creaking to and fro.”[6] Compounded with this horrific sight was the gibbet post itself; sometimes standing as high as thirty feet, the post could be studded with “thousands” of nails to prevent the body being stolen, or coated in lead to prevent its being burned down.[7]

Print culture helped to promote a link between sailors and gibbeting, as authors such as Charles Dickens, Sir Walter Scott and poet William Wordsworth featured wayward seafarers who suffered the gruesome fate of being exhibited in public after execution. Wordsworth’s cautionary tale, Adventures on Salisbury Plain centres on a sailor who has a chilling encounter with a gibbet only to end up as a grisly occupant of an “iron case” himself, subsequently viewed with horror by others.[8] In Dickens’ The Old Curiosity Shop, the villainous Quilp’s body is washed up by the river “where pirates had swung in chains, through many a wintry night” whilst Scott’s novel, The Pirate was thought to have been based on the case of John Gow, a Scottish sailor who took to piracy and was executed along with seven of his crew at Execution Dock in 1725.[9] Hartshorne tells how Gow allegedly refused to plead at his trial, but upon realising that he was to be tortured to death if he did not speak up, stated that he: “would not have given so much trouble if he could have been assured of not being hung in chains.” Gow, however, was subsequently convicted, “and gibbeted in the chains he so much dreaded.”[10]

This fear of gibbeting after death was not only provoked by the shame and stigma attached to being exhibited as a criminal, potentially for years to come, but appears to have been heavily centred on the religious connotations of the condemned not receiving a proper burial. That criminals (and their relatives) should fear that the unburied would be denied resurrection in the afterlife, suggests an adherence to traditional religious values, which ran counter to modern scientific consensus viewing bodies as “merely the shells we cast off at death.”[11] The punishment of hanging in chains may have been imbued with particularly ominous symbolic resonations for the religious wishing to avoid damnation due to scriptural passages referencing “angels of destruction” who tormented sinners in hell by hanging them in “chains of fire”.[12]

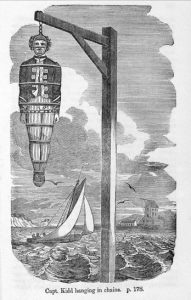

Whilst the vast majority of gibbet occupants appear to have been males, the nineteenth-century illustrator George Cruikshank was appalled to see the gibbeted bodies of two women hanging outside Newgate Prison in 1818.[13] The reluctance to gibbet women perhaps stems from public angst regarding “the post-mortem treatment of the executed female body” inflamed by rising social stigmas surrounding women being present in the public sphere in general during the period.[14] The gibbeted bodies of foreigner sailors were a more common sight, however, according to one correspondent to the Leicester Chronicle in 1884, who describes the profusion of gibbeted bodies hanging on the Thames at Blackwall Point, opposite the East and West India Docks. These were “mostly Lascar sailors” gibbeted at that point so that they would be seen by other Lascar sailors passing by in crews on the river.[15] These figures were joined in chains by infamous pirates such as Captain Kidd and James Lowry who were also hung in chains by the Thames after having being executed publicly at Execution Dock in Wapping.[16] One newspaper correspondent noted in 1883 that those gibbeted on the Thames for the crime of piracy were not necessarily sea-going vigilantes, but that the punishment was also extended to those who robbed ships on the river.[17] Taverns within the vicinity apparently had “spy-glasses” attached to their windows for customers to use, and when these were removed, there was an outcry in several papers, complaining that Londoners had been “deprived of their amusements, in not being able to enjoy the view of these pirates.”[18] Thus, not everyone recoiled in fear from gibbeted bodies, in fact public hangings and gibbetings, far from striking fear into the hearts of locals appear instead to have attracted crowds. Hartshorne observes that in 1792 “after the English rural fashion” a gingerbread stall was set up to accommodate the hordes wishing to the view freshly gibbeted body of an infamous highwayman in Attercliffe Common.[19]

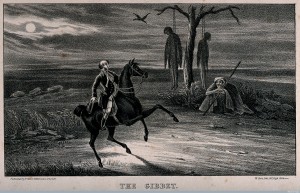

The location of the gibbet certainly seems to have been an important factor when considering the impact of the spectacle upon passers-by. The placement of gibbets within social liminalities: spots such as rivers, cross-roads, bridges and boundaries made them visible to anyone entering or leaving the vicinity, and served to heighten their message of social excommunication, and the transition state inhabited by criminal transgressors who, suspended above the ground were seemingly caught between heaven and earth.[20] Joris Coolen notes that in the Shetland Islands, visibility from harbours and the sea was an important factor for gibbet placement, presumably as a warning to outsiders of what might happen should they violate local laws.[21]

That gibbets were frequently the site of reported hauntings and developed their own brand of gibbet folklore–usually centered around sepulchral voices emanating from the corpse to frighten young men embarking on wagers designed to test their mettle–is perhaps unsurprising given their otherworldly and frightening aspect.[22] The ghosts of these executed criminals seem not to have strayed too far from the site of their gibbets; a newspaper report from 1934 relates the tale of the last man to be gibbeted at Broadbury Castle in Devon for killing three women “for a long time the inhabitants of the district walked in fear of their lives at night near the spot where the gibbet stood–all on accounts of the murderer’s ghost”.[23] A prime maritime example of this phenomenon is that of James Aitkens’ ghost, a man who was executed in 1777 for attempting to burn down Portsmouth Dockyard.[24] Aitkens, known as “Jack the Painter” was hung in chains after death at the entrance to Portsmouth Harbour and his ghost was thereafter said to pace the harbour at night near Blockhouse Point, the site were his gibbeted body had been displayed until it was removed in the 1820s.[25]

Considering the above, it is evident that gibbets provoked different emotions in different audiences. Accounts of those condemned to be hung in chains suggest that criminals held a particular dread of this punishment, perhaps because they feared forfeiting a chance of a redemptive afterlife by not receiving a proper burial. Contradictory accounts of observers’ reactions to gibbeted bodies exist, however, but notable trends are discernible. The freshly executed body appears to have been something of a popular attraction, though the bodies of pirates dangling over the Thames continued to draw spectators even after this event had passed. Presumably, these viewings took place during daylight hours, yet once night fell, especially in more remote locations, gibbets seem to have become taboo sites to be avoided for fear of disturbing their restless spirits. Written musings regarding the history of gibbets appear more frequently in newspapers towards the end of the nineteenth century as by then the threat of gibbeting presumably remained far enough in the past as to not seem too freshly horrific. It is most frequently the gibbets of sailors and notorious pirates that draw the most interest from commentators, both literary and in popular journalism, perhaps alluding to a macabre romanticism for the golden age of piracy, one enjoyed at a safe temporal distance.

[1] Sarah Tarlow, “The Technology of the Gibbet,” International Journal of Archaeology, vol. 18, no. 4, (2014): 668.

[2] Tarlow, “Technology,” 669.

[3] Owen Davies, The Haunted: A Social History of Ghosts, (Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2007), 53.

[4] Albert Hartshorne, Hanging in Chains (New York: The Cassell Publishing Company, 1893), 25.

Retrieved from https://archive.org/details/hanginginchains00hart

[5] Harry Potter, Hanging in Judgement: Religion and the Death Penalty in England from the Bloody Code to Abolition, (London: SCM Press, 1993), 74.

[6] Hartshorne, Chains, 74

[7] Potter, Hanging, 73.

[8] Quentin Bailey, ““Strike not from Law’s firm hand that awful rod”: Wordsworth’s Salisbury Plain and the Penalty of Death,” European Romantic Review, vol. 21, no. 2, (2010), 240.

[9] Tyson Stolte, “’And Graves Give Up Their Dead’: The Old Curiosity Shop, Victorian Psychology, and The Nature of the Future Life,” Victorian Literature and Culture, vol. 42, (2014), 196; Hartshorne, Chains, 60; “Classified Adds: Newly Published,” London Journal Issue CCCXV (Saturday, August 7, 1725); British Newspapers 1600-1950. Gale Document Number: Z2001384698.

[10] Hartshorne, Chains, 60.

[11] Stolte,“Victorian Psychology,” 197.

[12] Hartshorne, Chains, 2; “The Revelation of Moses: Heaven, Hell and Paradise,” Gedulath Mosheh (Amsterdam: V. Jellinek, Beth Hammidrash, 1854), quoted in M. Gaster, “Art XV.—Hebrew Visions of Hell and Paradise.” Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society, vol. 25, no. 3 (1893), 581.

[13] Alex J. Dick, “The Ghost of Gold”: Forgery Trials and the Standard of Value in Shelley’s The Mask of Anarchy,” European Romantic Review vol. 18, no. 3, (2007), 397 fn. 11.

[14] Owen Davies and Francesca Matteoni, “A Virtue Beyond All Medicine’: The Hanged Man’s Hand, Gallows Tradition and Healing in Eighteenth and Nineteenth-Century England.” Soc Hist Med (first published online May 2, 2015 doi:10.1093/shm/hkv044), 12.

[15] R. R. “Strange Gibbet Stories,” Leicester Chronicle and the Leicester Mercury issue 3801 (Saturday, January 26, 1884) 19th Century British Library Newspapers: Part II. Gale Document Number: R3208352087.

[16] Hartshorne, Chains, 78; “News,” Post Boy (London), issue 938 (May 22 – May 24, 1701) British Newspapers 1600-1950. Gale Document Number: Z2001401428.

[17] Surriensis, “Hanging in Chains,” Notes and Queries s6-VIII, issue 201, (03 November, 1883), 353. Retrieved from https://data.journalarchives.jisc.ac.uk/view?pubId=oup-notes-esnotesjnotesj_s6-VIII_201pdf353-bpdf&terms=%22chains%22&date=1883

[18] F.S.A, “Hanging in Chains, and Hanging in Irons,” Notes and Queries s5-1, issue 2, (10 January, 1874), 35.

[19] Hartshorne, Chains, 103.

[20] Karl Bell, The Legend of Spring-Heeled Jack: Victorian Urban Folklore and Popular Cultures (Woodbridge: Boydell, 2012), 158; Joris Coolen, “Places of Justice and Awe: the Topography of Gibbets and Gallows in Medieval and Early Modern North-Western and Central Europe,” World Archaeology, volume 45, no. 5, (2013), 774.

[21] Coolen, Topography, 769, 771.

[22] Bell, Legend, 158; William Andrews, “Echoes of the Olden Time,” Leicester Chronicle and Leicester Mercury issue 3797 (Saturday, December 29, 1883) 19th Century British Library Newspapers: Part II. Gale Document Number: R3209283707.

[23] “The Devil Died at North Lew,” The Western Times (Exeter) issue 33410, (Friday, October 12, 1934), 9. British Newspapers, Part III: 1780-1950. Gale Document Number: GW3219464590.

[24] Karl Bell, “Civic Spirits? Ghost Lore and Civic Narratives in Nineteenth-Century Portsmouth.” Cultural & Social History, vol. 11, no. 1, (2014), 12.

[25] Bell, “Civic Spirits,” 12.

Great article, Eilís. I did not pick up on the difference between gibbeting and hanging until you mentioned it. I had heard that some bodies were tarred to ensure shelf-life. How early is the practice, do you know? Hanged corpses are mentioned in one of the Grimms’ fairy tales. I rewrote it for a collection that is hopefully coming out some time this year

Thanks for you comments Jim, and really glad you enjoyed the article. It’s interesting that you bring up tarring as there seems to be some confusion over why bodies were tarred, but yes, in the sources I’ve found preservation appears to be a motive. In one source from Notes & Queries a gibbeted body was apparently smeared with tar for sanitary purposes. The author remarks that otherwise, after a week or so, the body would have become an “intolerable nuisance”!

As for dating the practice in Britain, the earliest account I’ve found appears in an 1884 Leicestershire newspaper article which suggest the practice goes back to the Anglo-Saxon period, but that the practice was known as gibbeting from the thirteenth century onwards. The author cites an example of gibbeting from 1236 recorded by Matthew Paris, in which one man was gibbeted alive, the other dead.

Thanks for mentioning the hanging corpses in Grimms’ Fairy Tales, you’ve reminded me that I am long overdue to re-visit them, I’ll keep an eye out for your collection!

Fascinating if macabre piece.

Am I correct in saying that the touch of a newly executed felon was valued for medical purposes?

Similarly, were so-called Hands-of-Glory likely to be made from such dead criminals?

Thanks.

Thanks for reading, and for your comments. Yes the touch of freshly hanged (specifically male) corpses was thought to cure a variety of skin ailments, usually localised swellings such as tumours or goiters, a practice which peaked in the latter half of the eighteenth century.

As for the Hand of Glory, it involved cutting off the newly hanged man’s hand, drying it, and preserving it. This might then be used alongside a candle made from the fat of a hanged man, with the intention of stunning anyone who saw it, rendering them motionless. The hand had to come from a freshly hanged corpse; executed bodies displayed on/in gibbets were deemed too decayed to retain the magical properties of their souls which the recently executed were still thought to possess briefly after death.

If you want to read more, I’d strongly recommend the following article which I’ve used as a reference point, and is available to download for free from Owen Davies’ academia.edu profile page:

Owen Davies and Francesca Matteoni, “A Virtue Beyond All Medicine’: The Hanged Man’s Hand, Gallows Tradition and Healing in Eighteenth and Nineteenth-Century England.”

Thanks for the link,never knew this,interesting.

Thank you Mayank, glad you got the link okay!

This is a really interesting article! I thoroughly enjoyed reading it.

I found it particularly interesting that you mention the differences in reaction to gibbet cages in terms of placement. I.e. those found between the boundaries of different cities seemed to hold a fresh form of threat compared to those hung within cities and towns.

I was wondering, do you think the crowds that hoarded to see these spectacles played a part in the popular culture of violence, encapsulated by Rosalind Crone, that emerged during this period?

Super article! Thank you!

Thanks for reading Grace!

I think that it’s interesting that you raised the point about the relative threats of different gibbet locations. Where gibbets were placed in a more urban context they were still on the peripheries i.e by docksides. This nearness to the hustle of city life may have made them slightly less threatening yes, whilst still keeping them at a safe distance.

As for a culture of violence, I’d say that the act of gibbeting (as in public hanging) would certainly have attracted crowds which authorities would have been wary of, especially given the bloodthirsty nature of the entertainment – but the gibbets themselves after hanging had taken place appear to have become more an elite talking-point and source of folklore narratives than sites inciteful of popular violence. Though I would be interested to explore this idea further – thanks!

Interesting article but smugglers were not executed for smuggling. The offence was depriving the Government of Customs income, convicted offenders could lose all the confiscated dutiable goods, have their vessels sawn in half and then sold and be personally fined £100. If they failed to pay the fine they were imprisoned. Of course if they violently resisted the Revenue men then they laid themselves opened themselves to facing trial for capital offences. If this was not the case then many port towns would have been decimated from smugglers being executed

Many thanks for the correction, Tony. Yes it seems that smuggling was listed alongside other offences e.g murder when gibbeting of smugglers was called for.