The naval town of Portsmouth, located on the south coast of Britain, had a rich cinema culture in the early 20th century. At the peak of the leisure habit’s popularity in the 1930s and 1940s, the town was home to 29 cinemas. These ranged from the plush ‘picture palaces’ to the smaller, rudimentary cinemas. The larger halls would have attracted cinema-goers from across the town, but the many smaller cinemas would have only attracted patrons living in the local area. The Queens cinema, the focus for this article, was of the smaller type, accommodating roughly 500 patrons. The cinema was located in Portsea, the heart of Portsmouth’s sailortown, and would have attracted cinema-goers who lived in the immediate vicinity along with those working in and around the Dockyard and naval barracks, including naval personnel. By analysing film booking patterns for this cinema we can begin to identify the likes and desires of this particular group of cinema-goers.[1] What films did they want to watch?

The naval town of Portsmouth, located on the south coast of Britain, had a rich cinema culture in the early 20th century. At the peak of the leisure habit’s popularity in the 1930s and 1940s, the town was home to 29 cinemas. These ranged from the plush ‘picture palaces’ to the smaller, rudimentary cinemas. The larger halls would have attracted cinema-goers from across the town, but the many smaller cinemas would have only attracted patrons living in the local area. The Queens cinema, the focus for this article, was of the smaller type, accommodating roughly 500 patrons. The cinema was located in Portsea, the heart of Portsmouth’s sailortown, and would have attracted cinema-goers who lived in the immediate vicinity along with those working in and around the Dockyard and naval barracks, including naval personnel. By analysing film booking patterns for this cinema we can begin to identify the likes and desires of this particular group of cinema-goers.[1] What films did they want to watch?

The first thing that stands out when analysing booking patterns across the whole period of the cinema’s operation is the sheer dominance of films of and about the sea. Of course, the regular booking of sea-faring films in a naval-town cinema is perhaps predictable, but the consistency with which such films were exhibited is astonishing, and is certainly a product of this cinema’s patrons’ close connections with naval life. It would appear that these types of film were booked by the cinema’s managers to remind their patrons of their close connections with the sea. As such, they provided recognition; they were signifiers of the audiences’ shared way of life and could offer comfort and reassurance in a changed and frequently challenging world. What other patterns can be identified?

In the years following the First World War and leading up to the Great Depression in 1929 booking patterns suggest that drama films, particularly patriotic dramas, were most popular. The cinema’s managers clearly expected this type of film to appeal, for they were often advertised with an endorsement of their patriotic qualities. The Hollywood epic For Liberty (1917) was thus advertised as a ‘Patriotic Play’.[2] Many of these films were ‘war-touched’, drawing on events in the First World War to drive their narrative and offering to help cinema-goers recover from the traumatic psychological effects of the conflict while also letting them come to terms with the war’s effect on class and gender relations.[3] It would seem that patrons of this cinema were expected to use these films to honour their involvement in the conflict and help them negotiate a path through society in the post-war world.

The other type of drama booked with frequency during this period was the morality tale. As with the patriotic dramas, advertisements noted these qualities.[4] If we consider thematic patterns in these films, one strand is common: they can be read as a warning against sexual transgression. In fact, infidelity, and the dangers associated with it, is a recurrent theme. However, the characters in these films were not irredeemable; they could be saved. The redemption motif was, in fact, central to many of these morality tales. It could be argued that the Queens’ managers were attempting to use this type of film to address contemporary concerns about post-war gender relations, helping their patrons negotiate a path between acceptable and improper behaviour.

Significantly, Portsmouth’s sailortown had a historically disreputable image and had long been associated with licentiousness and immoral behaviour.[5] These concerns were exacerbated in the early-20th century with the increasing popularity of cinema. Indeed, the supposed demoralizing forces at work in the film medium led to a number of morality campaigns by religious and purity crusaders across Britain to protect the more ‘susceptible’ cinema patrons – including children, the working classes and seafarers – from cinema’s harmful influences.[6] The Queens’ managers – aware of their business’s negative associations – could thus use this popular leisure medium to urge their patrons to adhere to strong moralistic social protocols. However, for films such as these to be successful, they had to package their critique in an acceptable manner, and it was the redemption motif that appeared to satisfy these cinema-goers.

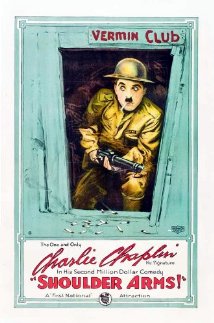

The next most popular film genre at the Queens in this period was comedy, and once again, a film’s likelihood of being exhibited depended on how it dealt with its subject matter. Booking patterns reveal that the biggest draw was Charlie Chaplin; an artist whose work frequently dealt with contentious social issues, but whose use of humour served to mask his brand of cutting social criticism. Like the social conscience tales, these films offered audiences a safe environment in which to address often challenging contemporary issues. It would appear, therefore, that the Queens’ patrons were using cinema to deal with the realities of their day-to-day lives. Films could help them honour their successes, they could offer to resolve moral ambiguities, and they could suggest ways in which to deal with the sweeping changes taking place in the post-war world. In such ways, these cinema-goers could use films to gain comfort and reassurance.

During the 1930s booking practices suggest that dramas were again the most popular film genre with the Queens’ patrons with comedies once more running a close second. The most frequently booked type of film, however, was the American crime drama. All these films booked featured tough men and feisty women; many featured the same popular stars playing very similar roles. They also shared very similar thematic patterns, so audiences would have known what to expect from them. Crime dramas opened up a space in which audiences could imagine a world with very few restrictions. However, those individuals who transgressed social boundaries were always punished or redeemed. These films thus performed a dual function: they let cinema-goers enjoy a sense of abandon and they acted as a moral compass. Some of the comedy films booked in the 1930s functioned in a similar manner – they allowed audiences to mock the existing social system, but in a way that did not threaten it. This surely had much to do with the patrons’ naval connections, where a strict social structure, with a clear order, and where an unambiguous respect for authority, is expected. Again, these films offered audiences a safe environment in which to address difficult issues.

During the 1930s booking practices suggest that dramas were again the most popular film genre with the Queens’ patrons with comedies once more running a close second. The most frequently booked type of film, however, was the American crime drama. All these films booked featured tough men and feisty women; many featured the same popular stars playing very similar roles. They also shared very similar thematic patterns, so audiences would have known what to expect from them. Crime dramas opened up a space in which audiences could imagine a world with very few restrictions. However, those individuals who transgressed social boundaries were always punished or redeemed. These films thus performed a dual function: they let cinema-goers enjoy a sense of abandon and they acted as a moral compass. Some of the comedy films booked in the 1930s functioned in a similar manner – they allowed audiences to mock the existing social system, but in a way that did not threaten it. This surely had much to do with the patrons’ naval connections, where a strict social structure, with a clear order, and where an unambiguous respect for authority, is expected. Again, these films offered audiences a safe environment in which to address difficult issues.

So, there were continuities in the tastes of the Queens’ patrons between 1914 and 1939. It took the trauma of the Second World War, in which Portsea came under sustained air attack in a series of blitzes, to generate a significant impact on their tastes.[7] Booking patterns for the post-war period reveal that it was comedies, not dramas, that were the biggest draw. The pressures of war required a different type of film to be shown to ease audience concerns. A number of thematic patterns dominate in the comedies exhibited. The most recurrent theme concerned the subject of duplicity. Films in which dishonest and fraudulent behaviour was displayed were regularly booked. However, in all these films those in the wrong were either punished or redeemed, while those who were morally upstanding were rewarded for their virtuous behaviour.

We can see continuities with the earlier periods here; redemption continued to be a regular motif. Films dealing with the recent conflict or its aftermath account for the second most booked type of comedy at the Queens in the post-war period. As with the immediate post-First World War period, then, it appears that the Queens’ managers were trying to use certain films to reassure their patrons of their place in the post-war world. In fact, solutions to post-war difficulties were regularly addressed in the third most booked type of comedy: romance. Most of these films dealt with the issue of infidelity or marital breakdown. As with the post-First World War period, this cinema’s managers were booking films implicitly dealing with the war’s effect on society’s relationships. The resolutions offered suggest that audiences were expected to use them when negotiating the tricky return to normality.

While booking patterns suggest that audiences were gaining more pleasure from comedies than dramas in this period, the latter were booked in respectable numbers. In addition, of the dramas shown, the war clearly functioned as a source of encouragement. Indeed, the number of dramas booked that depicted events from the recent war was even higher than that of films featuring the First World War in the years following that conflict. However, the type of film booked with most frequency presented only positive interpretations of the Second World War, which surely reveals much about the audience’s need for reassurance.

While booking patterns suggest that audiences were gaining more pleasure from comedies than dramas in this period, the latter were booked in respectable numbers. In addition, of the dramas shown, the war clearly functioned as a source of encouragement. Indeed, the number of dramas booked that depicted events from the recent war was even higher than that of films featuring the First World War in the years following that conflict. However, the type of film booked with most frequency presented only positive interpretations of the Second World War, which surely reveals much about the audience’s need for reassurance.

By mapping booking patterns at this local sailortown cinema it has been possible to establish which films were expected to be popular with its patrons, and allows us to begin to gauge their popular mentalities and social attitudes. Clearly, their moviegoing habits were shaped by the effects of external forces on their urban environment – war; economic depression – but the data suggests that the Queens’ managers booked films that they believed answered directly to their patrons’ tastes, whatever the circumstances. So, by mapping this community’s movie-going habits we can begin to uncover the huge influence naval life had on the people within it – going to the movies helped to shape them and their attitudes towards the outside world.

* This post is an abbreviated and modified version of a previously published article, Robert James, “Cinema-going in a Port Town, 1914-1951: film booking patterns at the Queens Cinema, Portsmouth.’ Urban History 40, no. 2 (2013): 315-35.

[1] Booking patterns have been identified using advertisements placed in the local paper, the Portsmouth Evening News.

[2] Evening News, 9 November 1919.

[3] Christine Gledhill, “Late Silent Britain”, in The British Cinema Book ed. Robert Murphy. (London: Palgrave Macmillan, 2008). 163-176; 165-166

[4] For example, Souls Redeemed (1917) was described as “The Great Moral Play”. Evening News, 9 October 1920.

[5] John Webb, “Leisure and Pleasure”, in The Spirit of Portsmouth: A History eds. John Webb, Sarah Quail, Peter Haskell and Richard Riley. (Chichester: Phillimore & Co. Ltd. 1989). 141-153; 142.

[6] For a more detailed analysis of film censorship in this period see Annette Kuhn, Cinema, Censorship and Sexuality 1909-1925 (London: Routledge, 1988).

[7] Between July 1940 and May 1944 Portsmouth experienced 67 major air raids. The three main attacks took place in August 1940 and January and March 1941. See Peter Haskell, “A Changing City”, in Spirit of Portsmouth eds. Webb et al., 169-176; 169.

Comments are closed.