I’m delighted to introduce our seventh guest post, by Madison Heslop. She is a PhD candidate in History at the University of Washington. While there is a well-known and rich literature on “the idea of the city” or “the image of the city,” there’s a surprising shortage of smart, thoughtful pieces on where waterfronts and harbors fit in. A book by Josef W. Konvitz, Cities and the Sea: Port City Planning in Early Modern Europe, made a valiant effort on this many decades ago, and I took a shot at it for the eighteenth century in my essay “Humours of Sailortown” that appeared in the edited volume City Limits, but Madison Heslop’s focus here is an unconventional and refreshing approach to visions of the twentieth century waterfront, and she takes it all the way up to recent representations in video games. Her reference to Gotham as “Manhattan below Fourteenth Street,” by the way, follows neatly on my last post, about my visit to New York City’s South Street Seaport Museum and the surrounding neighborhood. — I.L.

Has any city been so closely associated with crime as Gotham, the fictional home of Batman? More than Liverpool or New York City—the latter of which Gotham is a dark mirror—the name Gotham City evokes mental landscapes of grime, violence, and corruption. Historian Bradford W. Wright has described Batman’s city as a “claustrophobic netherworld,” populated by “the most grotesque and memorable villains ever created for comic books.”[1] Gotham may not immediate conjure images of cranes, shipping containers, and fish markets, but it represents the ultimate port city in the popular imaginary because it embodies everything that people most feared about ports, dockyards, and the communities who inhabited them in the twentieth century.

Gotham was founded in 1635 by … just kidding. Typical of comic book settings, Gotham’s history is so muddled as to be almost meaningless.[2] Even so, Batman’s early writers and artists borrowed the city’s landscape from their New York surroundings, including the name. “Gotham” has been shorthand for that city’s grim history of poverty and crime for well over a century.[3] Batman writer and editor Dennis O’Neil describes Batman’s Gotham as “Manhattan below Fourteenth Street at eleven minutes past midnight on the coldest night in November.”[4] Those southern Manhattan neighborhoods include some of New York’s most notorious districts and provided the setting for Herbert Asbury’s sensational portrait of the city’s “underworld,” The Gangs of New York.[5]

Waterfront neighborhoods have historically been multicultural and working class. Chinatowns and other ethnic neighborhoods have a history of growing on or near ports.[6] Port districts’ association with racialized and working-class communities in the nineteenth and twentieth-century United States predictably exacerbated longstanding attitudes that linked dockyards with violence and crime. Dock work was a male-dominated form of labor that lawmakers, historians, and others have associated with militancy, casualism, tight communities, and anti-authoritarian politics.[7] While Robert Lee has clarified that the image of “Jack in port” as a raucous and violent character was based on too restrictive an understanding of sailor’s lives ashore, sailor’s bad reputations were well established by the sixteenth century.[8] Even Lewis Mumford, the great lover of Manhattan, despaired that inadequate roads and accommodations in commercial port cities left sailors and dockworkers to the tender mercies of the taverns and brothels surrounding the docks prior to World War II. Their “degradation,” he wrote, “not merely infected the waterfront proper, but spread to other quarters of the city.”[9]

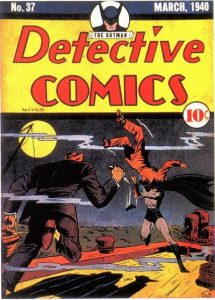

The imaginative casting of dockyards as sites of criminal acts had a persistent legacy in twentieth-century storytelling. This legacy has been evident in Batman comics from their beginning. Detective Comics #27 features Batman’s first appearance, published in May 1939. Figure 1, which appears at the beginning of this post, is the cover of Detective Comics #37, just ten issues later, depicting Batman fighting two faceless men on a dim pier beneath a full moon.[10] The water is a sickly green and miasmic vapors drift between the figures. The story, titled “The Screaming House,” deals with espionage, with the waterfront as the scene for foreign intrusion and treachery. In Detective Comics #37, the urgency and anxieties about malignant incursion of the immediate pre-WWII moment inflected the association of dockyards with “foreigners” and crime.

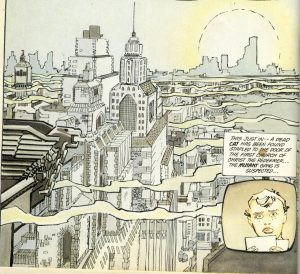

While always the site of crime, portrayals of Gotham took a darker turn in the 1970s. This turn coincides with the “urban crisis” characteristic of postwar industrial cities in the United States. If Gotham were a real place, the timing of the shift would match the real-time decline of port communities related to the shipping industry’s transition to containers.[11] New York Harbor in particular held a well-publicized reputation for corruption in the postwar decades that likely inspired further Batman adventures.[12] Frank Miller’s polarizing but influential 1986 graphic novel, Batman: The Dark Knight Returns further solidified the city’s dark and monumental look. Figure 2, from The Dark Knight Returns, echoes the cover of Detective Comics #37 in the fog and sickly colors of the city overlooking the finger piers at the waterfront.[13]

In the 2002 graphic novel Robin: Year One, the waterfront setting becomes shorthand for bleakness, decay, and the surety of criminal intent. Robin: Year One explored Robin’s early adventures for a new audience and new century. The first story in the novel uses a textless panel, Figure 3, depicting the Blackgate ferry terminal and surrounding docks to establish a tone of bleakness on the second page.

Later in the story, the Mad Hatter’s base of operations for a child trafficking scheme is a warehouse at the docks, visible in Figure 4.[14]

Recent Batman media continues to deploy this idea of dockyards as a natural setting for crime. Bruce Wayne’s first outing as Batman in Christopher Nolan’s 2005 film Batman Begins takes place in a container yard where gangsters are unloading contraband. Batman’s makes his base of operations a warehouse at one of Wayne Enterprise’s docks in the 2008 sequel, the Dark Knight, lending a new dimension to dockyards as a sphere of extralegal activity.[15] The 2015 videogame Batman: Arkham Knight grants the player (as Batman) free reign of the three islands that make up the game’s Gotham City, where they rescue hostages at Dixon Dock and Port Adams and rendezvous with Nightwing at the Ranelagh ferry terminal to track Penguin’s weapons smuggling network. Examining the latest year of Detective Comics, the lawless waterfront manifests in spectacular fashion in the form of Penguin’s “New Iceberg Lounge,” a casino and front for criminal dealing shaped like an iceberg in the middle of Gotham Harbor, illustrated in Figure 5. [16] At first glance, Detective Comics #958 may seem worlds away from issue #37, but the docks of Batman’s Gotham continue to occupy the same place in the cultural imagination they have for the last century.

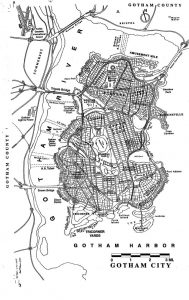

In 1998, DC Comics hired illustrator Eliot R. Brown to design a map of Gotham, Figure 6, for a team of writers and artists to reference as they worked on the Batman: No Man’s Land series. Brown has written about his experience designing the city:

“Like most comic book constructs, it had to do a lot of things. It needed sophistication and a seamy side. A business district and fine residences. Entertainment, meat packing, garment district, docks and their dockside businesses.”[17]

The old clock tower from which Oracle directs operations, Blackgate Prison’s island fortress, Crime Alley—most familiar to Batman fans as the setting for the murders of Bruce Wayne’s parents—they are all present. Brown’s was the first official map of Gotham, and in designing the city he gave it an implicit past that historians can read.

In his work on London’s eighteenth-century docklands, William Taylor has demonstrated that “fictional” and “factual” accounts of crime and commercial opportunity can be productively counterpoised in the process of analyzing narratives of London’s port community.[18] Similarly, thinking about Gotham can be useful not only for considering dockyards in popular culture, but also for analyzing the politics of port cities. Henri Lefebvre argues that cities are the setting for politics but they are also objects of struggle.[19] That struggle over control of Gotham and its Spaces, including the waterfront, plays out in the pages of comic books and even the digital terrain of video games. Gotham City may be more fiction than fact, but it has a history and even a geography based in reality that can be positioned alongside the histories of actual port cities to the benefit of better understanding both.

Madison Heslop is a PhD candidate in History at the University of Washington. Her work concerns the entangled histories of Seattle, Washington, and Vancouver, British Columbia, and their place in the Pacific in the early twentieth century.

Madison Heslop is a PhD candidate in History at the University of Washington. Her work concerns the entangled histories of Seattle, Washington, and Vancouver, British Columbia, and their place in the Pacific in the early twentieth century.

Notes

[1] Bradford W. Wright, Comic Book Nation: The Transformation of Youth Culture in America (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2001), 17.

[2] Curious readers may want to read Alan Moore’s Swamp Thing, no. 53 as well as the “Contagion” and “Cataclysm” storylines of Batman and the series Batman: No Man’s Land.

[3] Paul Reckner, “Remembering Gotham: Urban Legends, Public History, and Representations of Poverty, Crime, and Race in New York City,” International Journal of Historical Archaeology 6, no. 2 (June 2002): 95-112.

[4] Dennis O’Neil, “Afterword,” in Batman: Knightfall, A Novel (New York: Bantam Books, 1994), 344.

[5] Herbert Asbury, The Gangs of New York: An Informal History of the Underworld (New York: A.A. Knopf, 1928).

[6] Lars Amenda, “China-towns and Container Terminals: Shipping Networks and Urban Patterns in Port Cities in Global and Local Perspective, 1880-1980,” in Carola Hein (ed.), Port Cities: Dynamic Landscapes and Global Networks (London: Routledge, 2011), 43-53.

[7] Alice Mah, Port Cities and Global Legacies: Urban Identity, Waterfront Work, and Radicalism (London: Palgrave Macmillan, 2014), 9.

[8] Robert Lee, “The Seafarers’ Urban World: A Critical Review,” International Journal of Maritime History XXV, no. 1 (June 2013): 23-64.

[9] Lewis Mumford, The City in History, (New York: Harcourt, 1961), 420.

[10] Bill Finger, Bob Kane, and Jerry Robinson, “The Screaming House,” Detective Comics, no. 37 (March 1940).

[11] For a case study, see Jo Byrne, “Hull, Fishing and the Life and Death of a Trawlertown: Living the Spaces of a Trawling Port-City,” in Brad Beaven, Karl Bell, and James Rober (eds.), Port Towns and Urban Cultures: International Histories of the Waterfront, c. 1700-2000 (London: Palgrave Macmillan, 2016), 243-264.

[12] Alan A. Block, “On the Waterfront Revisited: The Criminology of Waterfront Organized Crime,” Contemporary Crises 6 (1982): 373-396; Colin J. Davis, Waterfront Revolts: New York and London Dockworkers, 1946-61 (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2003).

[13] Frank Miller, Batman: The Dark Knight Returns (New York: Warner Books, 1986).

[14] Chuck Dixon, Scott Beatty, Robin: Year One (New York: DC Comics, 2002).

[15] Christopher Nolan, Batman Begins (Warner Bros. Pictures, 2005); Christopher Nolan, The Dark Knight (Warner Bros. Pictures, 2008).

[16] James Tynion IV, Raúl Fernández, and Alvaro Martinez, “Intelligence, Part 1,” Detective Comics, no. 958 (June 2017)

[17] Eliot R. Brown, “DC Comics Gotham City Map Story,” Eliot R. Brown, <http://www.eliotrbrown.com/wp/gotham-city-map.html/2> (accessed 17 April 2018).

[18] William M. Taylor, “Ports and Pilferers: London’s Late Georgian Era Docks as Settings for Evolving Material and Criminal Cultures,” in Brad Beaven, Karl Bell, and James Robert (eds.), Port Towns and Urban Cultures: International Histories of the Waterfront, c. 1700-2000 (London: Palgrave Macmillan, 2016), 135-157.

[19] Henri Lefebvre, The Production of Space (Oxford: Blackwell, 1991).

All images fall within fair dealing under UK copyright laws and fair use under US copyright laws.

- All images are small fragments of creative works and do not represent the “heart” of the works concerned.

- The images are being used for purposes of research/educational in an article about the entity represented by the image.

- These images do not present substitutes for the creative work concerned and their use does not pose any risk of preventing sales.

- Scans are not high quality and come from copies of the work concerned purchased by the author.

- Neither the author nor the institution that hosts the Coastal History Blog will earn revenue from this article.

- Free use alternatives do not exist.

Figure 1. Cover of Detective Comics #37 by cover artist Bob Kane (March 1940). <http://dc.wikia.com/wiki/File:Detective_Comics_37.jpg> (accessed 17 April 2018).

Figure 2. Panel from Batman: The Dark Knight Returns by Frank Miller, Klaus Janson, Lynn Varley (New York: Warner Books, 1986). Scanned from personal collection by Madison Heslop.

Figure 3. Blackgate ferry panel from Robin: Year One by Chuck Dixon and Scott Beatty (New York: DC Comics, 2002). Scanned from personal collection by Madison Heslop.

Figure 4. Warehouse panel from Robin: Year One by Chuck Dixon and Scott Beatty (New York: DC Comics, 2002). Scanned from personal collection by Madison Heslop.

Figure 5. Partial spread from Detective Comics #958 by James Tynion IV, Álvaro Martínez, Raúl Fernández, Brad Anderson, and Sal Cipriano (August 2017). Scanned from personal collection by Madison Heslop.

Figure 6. “Gotham City Map” by Eliot R. Brown, Eliot R. Brown, <http://www.eliotrbrown.com/0001.php> (accessed 17 April 2018).

Comments are closed.