Our first post of 2018 is a guest post by Harry Brennan, who recently completed a MA History degree at Cardiff University, focusing on early modern and Atlantic history. This is the fifth guest post that has appeared in the Coastal History blog. This contribution continues to stretch the geographical, regional, and comparative range of the inquiry. It is also one of the first attempts to explicitly relate coastal history to political and religious dissent. Harry Brennan’s deployment of words like “liminality” and “porosity” is also of theoretical interest. Are we interested in the coast as a place where a threshold is crossed (the liminal), as the place where outside influences seep into an inner region (the porous), or, as I have suggested in another post, as the place where many different things adjoin, jostle, or overlap (adjacency)? Newer terms like “paramaritime” spaces or “rhizomatic” networks may offer a more nuanced approach, although again we need to ask what we hope to gain by introducing each term. Exact word choice may matter a lot, and highlighting these different choices serves as a welcome reminder that the coastal history toolkit is still under development. – I.L.

Why Brittany Matters

Despite the distinctly maritime character of Brittany, many of the insights and opportunities provided by ‘New Coastal history’ have yet to reach its shores. Likewise, few English-speaking historians have brought the region into their own work. In this blog post, I want to explore why Brittany can and should be the focus of coastal historians, be they Anglophone, Francophone or even Bretonophone. Bringing my knowledge of the early modern Atlantic to bear, I will show how studying Brittany can provide methodological insights for historians everywhere. It can also provide illumination for early modern British historians, and potentially impact public understanding of ‘Celtic’ culture.

A Source of Methods and Ideas

As Dr Isaac Land noted on this same blog, we owe a debt to Gérard Le Bouëdec for his sustained analysis of Breton littoral spaces. Le Bouëdec’s work has introduced many useful French terms to the lexicon of coastal history; words like riverains and pluriactivité which summarise more abstract concepts in English. Crucially, he insists that liminality is an essential and distinctive trait of littoral landscapes and cultures. Francophone historians have thrown such terms and ideas around since the oceanic studies of Fernand Braudel, but Dr Land’s own article shows how recently they have become accessible for Anglophone academia. Searching thoroughly for histories of Brittany in English throughout my postgraduate studies, I found only a handful of results. The strongest example I found was John Allan’s study of Breton woodworkers in south-west Britain, 1500-1550, and this (very specific) example comes to us as recently as 2014.[1]

This chasm between French theory and Anglophone historiography is especially unfortunate due to the many geographic similarities between Brittany and its ‘Celtic’ neighbours in Britain. Saving analysis of the term ‘Celtic’ for below, it can certainly be said that Brittany’s volcanic geology and innumerable inlets mirror much British coastal geography. This is a parallel not to be sniffed at. In his study of Scottish firthland identities, David Worthington noted that geography ‘will perhaps always be a part of the debate.’[2] Even in the seventeenth century, observers like Joshua Sprigg defined western British coastal areas like Cornwall using the ocean, describing it as ‘enwrapt… on all sides’ by the sea. The many natural fortifications and harbours created by Britain and Brittany’s local geology (e.g., Milford Haven, Falmouth, Brest) has long been exploited by the British and French navies. If anything, these areas had too many harbours and inlets connecting their inhabitants to the maritime world. At least, too many when compared with these areas’ economic development. With regards to the same Scottish firthlands studied by Worthington, Daniel Defoe once called Cromarty (on the Moray Firth) ‘the finest harbour… left intirely useless in the world.’

This dynamic of maritime porosity afforded locals greater mobility than inland-dwellers, whilst allowing them to retain cultural practices distinct from their parent states. I’m aware that this idea largely treads on the toes of David Underdown’s ‘chalk and cheese’ history – the idea that upland, rural areas provided a greater space for dissent than accessible lowland areas.[3] However, this same geographic-cultural separation within the larger British and French polities has rarely been explored with regards to littoral spaces. Whilst correlation (between a remote, rugged landscape and distinct coastal cultures) is not causation, the relationship between littoral environments and littoral cultures still remains to be analysed in depth across the British Isles and French Atlantic coast.

Sprigg’s ‘sea’ surrounding Cornwall includes the River Tamar, seen here from my shoreline perspective on the Cornish side of the Hamoaze (Tamar estuary). Note the continued insistence on this dividing line.

This is particularly pertinent in the Breton case, given Brittany’s robust defence of local culture and language. A brief example of Breton culture mingling with dissent from the French lowland centre can be seen very clearly in (what British historians might call) the early modern period. During 1670s Revolts of the Papiers Timbrés, the Governor of Brittany (the Duc de Chaulnes) was frequently called an hoc’h lart: ‘the fat pig’ in Breton.[4] To pin down any more sustained links in a precise manner, Anglophone historians will need to work with French theorists like Le Bouëdec and engage with Breton coastal geography. The determination to trace coastal riverains’ inherently liminal identities, laid out in Dr Land’s article mentioned above, should further inspire such a study.

Approaching a New Study: The Scottish Firthlands

Some of the strongest analysis of these dynamics in the British Isles can be found in David Worthington’s studies of ‘firthlands’ in the north-east of Scotland. Demonstrating the ‘resonance’ of coastal history analyses, Worthington also notes the need for an article-length exploration’ of the ocean’s effect on coastal populations.[5] Like Bouëdec, Worthington claims that the majority of evidence now points toward coastal areas sharing ‘marine and landed elements.’ Evidence of pluriactivité appears harder to trace in the Scottish firthlands than in Brittany, but there were certainly many Scots thoroughly involved in the ‘protomaritime’ economy.[6] Likewise, local men and women exploited maritime mobility whilst retaining distinct cultural practices. Throughout the early modern period, many spread out across northern Europe from maritime localities which still retained distinct Gaelic dialects, e.g., Brora and its Cataibh form of Gaelic.

St Malo, the fortified port city which defied Henri IV’s orders to arrest Irish priests. Note the rocky shoreline and stout city walls.

Other historians have further hinted at the dual physical/ideological porosity of the early modern Scottish coast. I stumbled upon many of these when analysing littoral spaces in which anti-Anglican dissent could survive in the early modern British Isles. For example, historians like Siobhan Talbott have shown how maritime trade provided Scottish institutions (like the Kirk) with revenue and support networks from across Europe; from La Rochelle to Leiden; from Gdansk to Veere.[7] These ‘maritime highways’ helped Presbyterian theology reach Scotland in the first place, pouring into the country’s many firths.[8] Attempting to forge broader coastal history analyses of these dynamics (perhaps as part of a broad Atlantic history study), these lines of inquiry could be applied to Brittany. Someone approaching this topic could examine how the Parlement de Bretagne, Breton Estates and port authorities (such as St Malo) collected revenue and constructed support networks across Europe. Mirroring Le Bouëdec’s source base – parish records, lawsuits and government naval documents – would likewise form a strong foundation for exploring such parallels.

Studies of shipwrecking and local salvage customs in Scotland would further reinforce such a study, as Brittany has a fascinating equivalent: naufragés. This describes shipwrecks deliberately orchestrated by coastal inhabitants of Brittany. For readers of French, a first point of contact with these histories might be Éric Rondel’s Naufrageurs des côtes bretonnes (2017). Some British coastal areas – Cornwall in particular – have a parallel history of ‘wrecking’, yet only recently have Anglophone historians crafted similarly sustained analyses.

Take Bella Bathurst’s The Wreckers (2005). This work touches on the liminality of life in coastal areas so emphasised by Le Bouëdec, and explores how shipwrecks could be the difference between ‘living well and just getting by.’ Bathurst even provides some connection to Scotland, touching on a Scottish lighthouse built by Robert Louis Stevenson’s ancestors. However, in mentioning the ‘darker side of those lights’, Bathurst alludes to the many myths surrounding wrecking in Britain. Historians must sift through images of ravenous Cornish ‘wreckers’ (cemented in part by Daphne du Maurier’s Jamaica Inn (1936) in order to explore how coastal dwellers treated local shipwrecks.

More recently, Cathryn Pearce has created just such a study with regards to the British Isles, focusing on the Cornish example in Cornish Wrecking, 1700-1860 (2010). Pearce explores how ‘the immorality of the coastal poor’ was played up in print: communities were often depicted as vicious, pseudo-cannibalistic criminals. Like Le Bouëdec, Pearce covers a range of legal practices (wreck law) and the shifting social context of Cornish life. Rather than ‘evil wreckers’ luring ships to their doom, Pearce portrays local beliefs about salvage as complex; a natural part of liminal coastal life, tied into local cycles of feast and famine.

If we explore how British coastal experiences (such as wrecking) parallel those of Brittany, then the reverse is also worth looking at. How can Breton experiences be better understood using British examples? Returning to Scotland, Worthington notes how locals used brief firth-crossing voyages to practice Presbyterian exercises, defying powerful episcopalian families in Cromarty and Nairn.[9] Furthermore, this maritime space didn’t just enable religious dissent – it reinforced the local rejection of Anglicanism. In an illustrative example from 1638, the Bishop of Ross fled rioting crowds by boat as they threw the Anglican Prayer Book after him ‘in peeces… into the sea’! The ferry ports of the firthlands were naturally key nodes for these developments, linking land- and sea-based networks of communication. Examining the small ports and ferry landings of Brittany (and other British areas outside the Moray Firth), other similarly rewarding analyses could be produced.

Worthington also shows us how to balance analyses of these coastal networks – in analysing the Moray Firth, he consciously gives equal weight to both rural and urban areas. This challenges early modern Scottish narratives of ‘Highlands v. Lowlands’, moving beyond the ‘apparently unstoppable advance of influences from the south… into the Gàidhealtachd [Gaelic-speaking area]’.[10] Anyone attempting to produce an equally balanced study of the Breton coast would also benefit from Bill Marshall’s survey of French Atlantic history. Marshall recommends replacing problematic centre-periphery models with a balanced, ‘rhizomatic’ maritime framework. ‘Go[ing] beyond the shoreline’ as coastal and Atlantic historians, Marshall and Worthington remind us that we can see information move omni-directionally across the sea. Port cities certainly help us understand these movements, but they need not be the sole centre of a littoral analysis. Whilst Le Bouëdec already devotes plenty of time to rural areas of Brittany, these ideas provide a useful anchor of rubric for such studies in Brittany and the British Isles alike.

Why should English-speaking historians care about the Breton example?

St Goustan-du-Port, a Breton sea-port and prime example of dissent coming and going by sea: Benjamin Franklin arrived here in 1776 to negotiate a Franco-American alliance.

As well as promoting greater methodological exchange across the Channel, making Brittany a subject of coastal history could help Anglophone historians more directly. Anyone analysing the flow of information/ideas (such as Scottish Presbyterianism) into and out of Britain in the early modern period could include Brittany in their frameworks for broader context. Whilst studying religious dissent in early modern Britain’s ‘Celtic’ regions, including Brittany helped me to understand Anglican suspicions of difference in remote littoral areas.

For example, Privy Council minutes from 1603 record the fear of Catholic dissenters arriving in Britain by sea. Three years later, Shakespeare’s King Lear hinted at a similar awareness in English public consciousness:

“There is division,

… ‘twixt Albany [Scotland] and Cornwall;

… from France there comes a power

Into this scatter’d kingdom…

In some of our best ports”

(King Lear, III: I)

Though set further in the past, King Lear was intended to be relatable to contemporaries. This movement of people motivated by religion – ‘confessional migration’, in Worthington’s words – helped fuel Catholic dissent in the British Isles.[11] This was most successfully done in Ireland, and Brittany played an often-overlooked role in this Counter-Reformation dynamic.

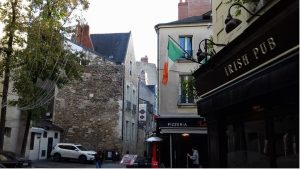

The Irish College in Nantes is still standing. I took this photo on a quiet autumn morning, Oct. 2017.

David Dickson and Jane Ohlmeyer have hinted at this when exploring the movement of Catholic priests between ‘continental colleges’ and the British Isles. Breton traders in St-Malo and Brest were known to carry Catholic priests past English naval patrols, ignoring the orders of Henri IV of France to arrest ‘Irish dissidents’.[12] Such links were even institutionalised in cases. The Parlement de Bretagne (in Nantes) gave alms to these priests, and ‘interconfessional agreements’ allowed priests trained in Rouen and La Rochelle to move safely between Breton ports and Waterford.[13] In Great Britain, many Breton traders permanently settled in Cornwall and Devon, allowing for even stronger cross-Channel ties.[14] All these scraps of evidence do not, however, amount to a detailed, peer-reviewed study. Brittany’s role as a ‘strategic crossroads’ for defence, trade and religion on the French Atlantic littoral (l’aire Atlantique) has not yet been explored in depth.

Public Impact: Understanding Our Celtic ‘cousins’

Finally, I want to reflect on what the cross-fertilisation of ideas discussed here could do for historians wanting to engage the public. If Brittany is a littoral region with both thematic parallels and direct ties to British coastlines, then how can this inform the identities and heritage of people in these areas? On that count, let me share an anecdote from a 2017 trip to Brittany.

Le Flambard, a small timber-framed bar in Lannion, hangs many Welsh flags prominently on its walls. Visiting on a November afternoon, I asked why the red dragon (y ddraig goch in Welsh) was flying in the heart of Brittany. Was the bar owner Welsh? Was it a rugby thing? Rather than these more straightforward explanations, the barman claimed this same dragon rouge represented Trégor, the locale around Lannion, ‘which was once its own country’. I later found out that Trégor boasts its own Breton dialect – Trégorrois – and Lannion has honoured its Welsh connection by naming a small town-centre car park le parking de Caerphilly.

Sensing the opportunity for a little ad hoc oral history, I asked if locals therefore felt some kind of cultural or historical connection to the Pays de Galles. Do they believe in some form of ‘Celtic’ identity, besides being Breton and/or French, which connects different areas across the sea?

The barman searched for the correct term. “Pas vraiment… le Pays de Trégor et le Pays de Galle… nous somme cousins,” meaning ‘Not really… Trégor and Wales… we are cousins.’ The term ‘cousin’ is illuminating. Rather than belonging to a romanticised Celtic brotherhood or pan-national polity, this Tregeriad simply believed that Wales and (his corner of) Brittany had a shared past. He saw the two as historically related, yet clearly distinct.

Many historians writing in English acknowledge Brittany as a ‘Celtic’ part of France, related to Britain’s Brythonic cultures in Wales and Cornwall, yet they rarely delve further. That term – ‘Celtic’ – is best used cautiously. In this context, it was popularised by nineteenth century Romantics, and remains associated with them. As Steven Ellis noted, many narratives centred on the ‘Celtic Fringe’ of the British Isles have over-emphasised the linguistic and cultural unity between these areas.[15] There are more effective ways to compare Brittany, Cornwall, Ireland, Scotland and the Isle of Man’s parallel littoral experiences, but these ideas are still nascent.

For example, Dr Land has outlined the historical ‘resonance’ between pluriactivity in Brittany, Cornwall and the Isle of Man. Seasonal activities like herring and pilchard fishing, which pulled normally land-bound workers onto the waves, were key to all three areas’ local economies. Indeed, this work was key to ‘scaveng[ing] enough calories to stay alive’ and maintaining some kind of semi-steady income. Crucially, however, Land does not claim that all three littoral areas shared some kind of monolithic ‘Celtic’ identity. Though I believe that effective coastal history analyses can be built on the parallels between Brittany and ‘Celtic’ areas of Britain, care must be taken. Anyone attempting to create such comparative analyses should avoid reinforcing what Tadhg ό Hannracháin calls ‘essentialist construct[s]’ of Celtic unity.[16]

This is what the barman in my anecdote reminds us of so succinctly. Brittany and ‘Celtic’ areas like Wales do share parallels and direct ties, but they should be seen more as ‘cousins’ than twins. Whilst my sample size of one hardly constitutes a detailed survey of ‘Celtic’ heritage, acknowledging this caveat should allow historians to construct more effective coastal history analyses here. For all coastal historians, I hope this provides food for thought.

Hailing from all corners of the British Isles, Harry recently completed a MA History degree at Cardiff University, focusing on early modern and Atlantic history. In 2015, he graduated from the same institution with a BA History degree, having completed a dissertation on the Iberian Military Orders and Reconquista. A prospective PhD student at Glasgow University, he intends to study how gender and identity were shaped by environments and movements across the early modern Atlantic. Beyond that, he finds the history of Atlantic shorelines, colonial expansion, masculinity and hybrid identities fascinating. Follow on Twitter @harryajbrennan and at academia.edu.

Hailing from all corners of the British Isles, Harry recently completed a MA History degree at Cardiff University, focusing on early modern and Atlantic history. In 2015, he graduated from the same institution with a BA History degree, having completed a dissertation on the Iberian Military Orders and Reconquista. A prospective PhD student at Glasgow University, he intends to study how gender and identity were shaped by environments and movements across the early modern Atlantic. Beyond that, he finds the history of Atlantic shorelines, colonial expansion, masculinity and hybrid identities fascinating. Follow on Twitter @harryajbrennan and at academia.edu.

Notes:

N.B. Photo credit: Harry Brennan, September and November 2017.

[1] John Allan, “Breton woodworkers in the immigrant communities of south-west England, 1500–1550,” Post-Medieval Archaeology, 48:2 (2014), pp.320-356.

[2] David Worthington, ‘The Settlements of the Beauly-Wick Coast and the Historiography of the Moray Firth,’ The Scottish Historical Review, 95:2 (2016).

[3] David Underdown, “The Chalk and the Cheese: Contrasts among the English Clubmen,’” Past & Present, 85:1, (1979), pp.25-48.

[4] Léon Er Ber (et al.), Istoér Breih pe hanes er Vretoned (Lorient, 1910).

[5] Worthington, Settlements.

[6] David Worthington, “Ferries in the Firthlands: Communications, Society and Culture along a Northern Scottish Rural Coast, c. 1600 to c. 1809,” Rural History, 27:2 (2016).

[7] Siobhan Talbott, “British commercial interests on the French Atlantic coast, c.1560–1713,” Historical Research, 229 (Aug. 2012), pp.394-5, p.400-3; Victor Enthoven, ‘Thomas Cunningham (1604-1669): Conservator of the Scottish Court at Veere’ in David Dickson, Jan Parmentier and Jane Ohlmeyer (eds.), Irish and Scottish Mercantile Networks in Europe and Overseas in the Seventeenth and Eighteenth Centuries (Gent: Academic Press, 2007), p.57.

[8] David Worthington, British and Irish Experiences and Impressions of Central Europe, c.1560-1688 (Farnham: Ashgate, 2012), p.125.

[9] David Worthington, “A Northern Scottish Maritime Region: The Moray Firth in the Seventeenth Century,” International Journal of Maritime History, 23:2 (2011), pp.206-7.

[10] Worthington, Settlements.

[11] David Worthington, “Migration and diaspora in European history prior to 1650: The Scottish and Irish cases,” Kultura – Historia – Globalizacja, 2 (2008), p.45.

[12] Mary Ann Lyons, “Reluctant Collaborators: French Reaction to the Nine Years’ War and the Flight of the Earls, 1594-1608,” Seanchas Ardmhacha: Journal of the Armagh Diocesan Historical Society, 19:1 (2002), pp.72-7; Guy Saupin, ‘Les Réseaux Commerciaux des Irlandais de Nantes sous le Règne de Louis XIV’ in Dickson, Parmentier and Ohlmeyer (eds.), Irish and Scottish Mercantile Networks, (Gent: Academic Press, 2007), p.121.

[13] Éamon Ó Ciosáin and Alain Loncle de Forville, “Irish Nuns in Nantes, 1650-1659”Archivium Hibernicum, 58 (2004), pp.168-9; Renaud Morieux, “Diplomacy from below and Belonging: Fishermen and Cross-Channel Relations in the Eighteenth Century,” Past and Present, 202 (2009), p.86 n.13.

[14] Allan, “Breton woodworkers”.

[15] Steven G. Ellis, “Why the History of ‘the Celtic Fringe’ Remains Unwritten,” européenne d’histoire, 10:2 (2003), p.222.

[16] Tadhg ό Hannracháin, “Introduction: Religious Acculturation and Affiliation in Early Modern Gaelic Scotland, Gaelic Ireland, Wales and Cornwall” in Robert Armstrong and Tadhg ό Hannracháin (eds.), Christianities in the Early Modern Celtic World (Basingstoke, 2014), p.1.

Hi, I am a big fan of your blogs. This is a great source of knowledge. Thank you very much.

The Sovereign House of Brittany, which bequeathed countless coats of arms the honour of ermine, descended from a 9th century salt merchant and courtier in Vannes (Gwened) who bore the Welsh name of Ridoredh.

The Celtic Sea is the unifier of peoples as far flung as the Portuguese, Galicians, Basques, Bretons, Cornish, Welsh, Irish and other peoples in the region. The prosperity of the trade plied by their ocean-going vessels was attested by Julius Caesar.

Thanks dude.. you’ve written all the aspects very clearly.. Keep writing 🙂