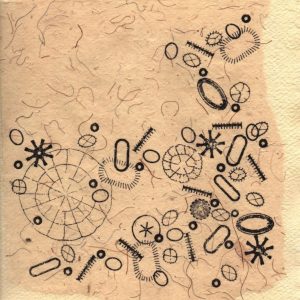

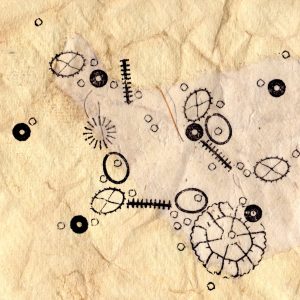

‘Smithereens’ Copyright Jo Atherton 2016 www.joatherton.com

In my last post, I discussed problems of scale. How can we visualize (and discuss) ocean-sized problems from our modest vantage point? Is the “oceanic selfie” a path to a higher level of consciousness, or an anthropocentric dead end?

When that post went online, I was in Hawaii and had just finished a couple days driving the circle route around the perimeter of the “Big Island.” It turns out that Hawaii is a good place to think about humans and nature, problems of proportion and problems of politics. The Big Island is a place where the visible human presence remains quite thin. There are small towns and airports, to be sure, but they are specks in a vast panorama of plains and jungle, mountain and sea, where it’s possible to fancy oneself in an unpopulated Eden or even—in the fields of lava rock—as the first crawling vertebrate on land.

A view uphill from Chain of Craters Road. Photo: Isaac Land

I have to say, after priming myself with a steady diet of Anthropocene-minded tweets, I was ready to see litter on the beaches and plastic floating in the ocean. But I didn’t. Places like the Big Island are an important reminder of why it’s sometimes hard to convince voters (and politicians) from the “wide open places” of the world—whether in the US, Australia, or Canada—that we’re overcrowded, overconsuming, and generally making a waste dump of the planet. It doesn’t look that way everywhere.

Driving the island was an exhilarating exercise for the monkey brain, full of tilting surfaces, tight turns, tremendous vistas, and hazards that leave you thinking about worst-case scenarios that would be impossible almost anywhere else. (If they ever make a reality TV show about Hawaiian tow truck drivers, it will be very entertaining.)

I didn’t have any true close calls, but negotiating some of those “scenic” curves left me with a palpable sense of what it would have been like to tumble over the guard rails, a projectile at the mercy of gravity, down to the lava plain a quarter mile or more below.

While I was feeling smug about my tactical cleverness, there were occasional reminders that some of the risks of Hawaiian driving fell in another category altogether. In more everyday settings, there are familiar concepts like “don’t drive into standing water,” but in Hawaii the integrity of the road itself is not a settled matter. Signs warn drivers to look out for fissures and rapidly developing, lava-spewing rifts; in effect, the warning could read: “Stay alert, the earth could swallow your vehicle.”

Warning sign overlooking Hōlei Sea Arch, Hawaii. Photo: Isaac Land

What to make of the peril that’s so large our monkey brain suggests no credible evasive action? I encountered this sign at the end of Chain of Craters Road. It shows how quickly our thinking becomes cartoonish as our imagination overloads. I suppose it is genuinely difficult to create a generic danger icon for these kinds of events, but these images seem to owe their inspiration to Edward Gorey or The Far Side. A flat tire is a problem, a narrow mountain road is a hazard, but a “huge wave” is either a slapstick joke, or a surreal intervention by an angry God.

I can see some parallels in the way that a lot of people react to policy questions on the big environmental issues. There isn’t a lot of middle ground between disbelief, and fatalistic despair. The reason that I’ve become interested in some fairly humble phenomena in internet culture, like coastal tweets and coastal blogs, is that they may offer a necessary bridge from our two-meter-sized egos, and our two-meter-sized everyday common sense, to the mega-structures and mega-impacts that define our era.

Beachcombers, mudlarks, and wreckers

We might expect bloggers and activists to adopt ultra-modern names for what they do, but there has been an interesting pattern of reviving terms with much older and more eclectic resonances. There is a popular twitter account by “Nicola White, Mudlark” (@TideLineArt) and a documentary about a marine debris investigator on the beaches of Cornwall is entitled The Wrecking Season.

Choosing to revive terms like wrecker and mudlark is whimsical at one level—I have to say it delights me as someone who has worked on the eighteenth century—but in a different way it affirms the sustained, serious endeavor; this is more than just a hobby or distraction. This is not to suggest that a one-day #beachclean or #rockpooling are intellectually vacant activities. But to self-identify as a wrecker or mudlark implies a more sustained commitment, in this case to follow up, look deeper, and make connections.

The artist Jo Atherton, who tweets @FlotsamWeaving , chooses to call herself a beachcomber. She writes:

“In my work, the tideline is a source of inspiration as I consider the stories behind the objects I find washing ashore, wondering how far they have travelled, who they belonged to and how long they have been at sea. Each object becomes a thread to be woven; strands of a story which tell of modern consumer habits, tastes and fashions.”[1]

‘Cornish Blue’ Copyright Jo Atherton 2014 www.joatherton.com

I like Atherton’s marine debris tapestries and prints of floating fragments (maybe plankton, maybe plastic) because they speak very directly to problems of scale (the micro and macro), consequences (the immediate and the remote), and even of what is sometimes called deep time or Big History. Plastic does not degrade on anything like a human time scale, and may well survive our civilization; Atherton remarks of her flotsam that we may be looking at the museum objects of the remote future. Her “flotsam prints” remind me of cave paintings. There is something timeless and eerie about these ambiguous objects suspended in space.

‘Written by a Wave Series’ Copyright Jo Atherton 2016 www.joatherton.com

Plastic debris is also an invitation to re-educate ourselves about geography. A study of a single, remote Maldives beach revealed 175 plastic water bottles originating in 10 different countries. The distant origins of the debris are invisible to the collectors, although the telephone and the internet permits intensive detective work. As this excerpt from The Wrecking Season shows, discovering a strange object on his doorstep provoked Nick Darke’s journey of discovery. Darke’s son, a marine biologist, draws a rough map for his father to explain how one of the world’s largest systems of ocean currents is propelling objects onto the Cornish beaches.

As with so many trends, this one has its own allied academic field with its own hashtag: #DiscardStudies. In the course of researching this blog post, I kept running into new publications with tongue-in-cheek titles. There’s Curtis Ebbesmayer and Eric Scigliano’s Flotsametrics: How One Man’s Obsession with Runaway Sneakers and Rubber Ducks Revolutionized Ocean Science, and Donovan Holm’s Moby Duck: The True Story of 28,000 Bath Toys Lost at Sea. But maybe the more interesting and important development is the emerging popularity with the general public. Following the 2011 tidal wave and Fukushima nuclear plant accident, some people adopted California beaches to record Japanese tsunami debris arriving on the far side of the Pacific. This tactile activity intertwined citizen science, activism, and beachcombing; the result was an intimate sense of ownership: “One volunteer, an older gentleman, brought along his wife, who was puzzled by her husband’s constant chatter about ‘his’ beach.”

As I discussed at the beginning of part two, there is ample evidence that it’s the “constant chatter” of people close to us that most reliably brings about a change in attitudes.

Coast Walkers

Elizabeth Albert spent three years walking New York City’s waterfront… or trying to. As she explains, “I drove and walked and sometimes I found that I couldn’t even get close to the water—huge power plants, fenced-off brown-fields, private property guarded by vicious dogs were often in my way.”[2] Her short essay makes for surreal reading. By way of abridgement, here is a list of scenes and images:

chain link fences

aluminum hangar-like structures

a path made of washed-out planks

hunks of Styrofoam

the mud steps heading down to the garbage-strewn shore

the flight path for planes landing at LaGuardia

the shoreline is wild scrub

some very old wooden fishing boats

a tiny orange crab, looking plump and alive

a towering brick apartment complex next to a massive Toys R Us

the Tallman Island Sewage Treatment Plant

This is difficult to digest. As Albert herself summarizes, what she saw was “beautiful, hideous, sad, and just weird.”[3]

That pattern is something I notice regularly in narratives of sequential coast walks, whether they are photo essays (like the excellent one that @QuintinLake is posting bit by bit on Twitter) or prose accounts like Albert’s. Industry, leisure, infrastructure, pollution, historic sites, and “nature” punctuate and intrude on each other in unpredictable ways.

All that the coast walker does, or sets out to do, is experience things in order: This is mile one, followed by mile two. The tone of many coast walking narratives, however, quickly becomes ironic. Here’s an enjoyable short blog post and photo essay about walking a stretch of France’s Cote d’Azur. It’s full of wry commentary, though my favorite image is of a unique, yet predictable, brand of flotsam: “On the stretch near San Tropez you could soon fill your pockets with champagne corks.” Coast walking may seem like an unlikely comedy genre, but visiting things in order turns out to pretty reliably produce disconcerting or hilarious disorder.

As with other forms of comedy, this wouldn’t work if we didn’t have conventions and proprieties ready for overturning. We have firm, if not fully articulated, ideas about what is supposed to be on the coast. The act of walking a long stretch of it and seeing what’s really there is difficult, and dissonant, because it juxtaposes things that we don’t expect to keep company with each other.

David Jarratt has conducted intensive interviews about the “sense of place” associated with seaside resorts.[4] Some of his results don’t apply very well to a generic coast, as when he interviews older British respondents about specific resorts that they have visited on and off since childhood (recalling “the taste of the ice cream” and “a win on the penny arcade”).[5] However, some of the terms that came up repeatedly in his interviews are quite relevant here. A visit to the coast is a form of escape, a place to “experience expanded thought.” The coastal zone is associated with spaciousness, vastness, timelessness, fresh air, peace, calm; it is something that won’t change, it is reassuring or comforting.[6] This is a complex set of expectations and experiences, for which Jarratt has coined the useful term “seasideness.”

This concept suggests new ways to interpret coastal itineraries and their narrators. Does the twenty-first-century coast walker recapitulate seasideness in a new eco-friendly idiom, or de-familiarize and disrupt it? In his prospectus for The Frayed Atlantic Edge: Learning Life, History, and Nature on the Coast, the historian and naturalist David Gange points out that we fall rather easily into the assumption that a coastal investigation would be carried out on land: “Extraordinary literary effort has been put into discussing the act of walking, yet self-powered travel on water has seen almost nothing in comparison…”[7] What happens, Gange asks, if we supplement the familiar “stout boots” with a kayak? His photographs suggest new vistas and a jarring, salt-splattered immediacy.

Another way of disrupting our expectations about the coast is to break out of “vacation mode” and really work at the job of observation. The scientist and novelist Ann Lingard writes:

“Having grown up with the cliffs and coves of Cornwall, when I first visited the apparently flat, apparently ’empty’ Solway shore at low tide I was disappointed. But time and frequent walks, guddling in the pools, checking out the tide-lines, meeting people who know about the coast and sea, has changed all that.”[8]

In contrast to the long-distance, sequential coast walkers, Lingard’s approach in Solway Shore Stories has been intensive, going over the same ground repeatedly and intensively from different angles and sharing the new perspectives over several years with readers of her series of blog posts that range across history, technology, and nature writing. (Her Twitter account is @solwaywalker). I find her interactive map of the region especially helpful; you can select a marked location and click through to a blog post about it.

When Lingard took a leisurely gyroplane flight over the Solway Firth, taking some stunning panoramic photos in the process (here is part one and part two), she was able to pepper those blog posts with links to earlier episodes in which she’d covered that ground on foot, or even half-immersed:

“The bore came rushing up the Firth, we heard its rasping chatter before we saw it. It was barely half-a-metre high, but the water quickly and silently flooded the shore in its wake. Twenty minutes later, I stood up to my waist in the Firth, gripping one bar of the great haaf-net; the water kept rising, up to my chest, it sucked the sand from beneath my feet… even on a quiet day the power of the water was obvious.”[9]

I think my first encounter with Lingard’s project was her closely-observed photo essay on the patterns and textures of sand:

“Chevrons, fish-scales, dimples: there doesn’t seem to be any logical reason why the ripples here should have a rounded profile while the ripples over there are taller and sharper; widely-spaced, or close together, or with tiny gullies down their sides.”[10]

My emphasis in part one was on altogether new forms of sea visibility. There, I discussed the way that new technologies are making innovative visualizations possible on our many screens and devices. The coast walkers are showing that some of the oldest methods still have new things to teach us. Serendipity, curiosity, and close, patient observation—including the willingness to re-visit a place, to look again—are indispensable arts, especially to new generations who may be more accustomed to exploring the “great indoors.”

Divers4Oceans, and Surfers against Sewage

Very little of what I’ve discussed so far directly confronts the kinds of conversations that happen in (and around) the great climate negotiations at places like Kyoto, Copenhagen, and most recently, Paris. A lot of those debates revolve around numbers like a 2 C warming, what that would mean, and when we might reach it.

Monitoring the changes in ocean temperature is, obviously, an important component of any well-informed approach to the rate and scope of climate change. The computer models that forecast global warming and sea level rise are only as good as the data we enter into them. Even NASA has recently invested in a research vessel—an actual sea-going ship—in order to obtain more granular data to cross-check what can be observed remotely by satellites.

How can ordinary people help? Derya Akkaynak, who recently received her PhD in oceanography from MIT, writes about her “Epiphany among the Manta Rays” while diving off of the Kona coast of Hawaii’s Big Island:

“Almost every scuba diver wears a dive computer on his or her wrist. These are battery-powered devices resembling wristwatches with oversized screens encircled by tiny buttons. Their primary purpose is to help divers keep track of how deep they have gone and for how long. But these computers are also equipped with thermistors, so throughout a dive, divers can check water temperatures at a glance… All of a sudden, I pictured divers as sensor platforms descending to the ocean bottom and sampling the water temperature—all hours of the day, day after day, all around the world.”[11]

Akkaynak founded Divers4Oceans as a way to make this vision a reality. Her central concept was finding a way to redirect just a little of the energy invested in a popular coastal leisure activity into a greater cause. Akkaynak’s project is in the early phases, but Surfers against Sewage offers an example of how this kind of endeavor can really acquire a momentum of its own. According to the SAS website, it “was established as a single-issue campaign group in 1990 by a small collective of passionate, local surfers and beach lovers in the picturesque north coast villages of St Agnes and Porthtowan [in Cornwall], the organisation swiftly created a well-known movement calling for improved water quality UK-wide.”[12] It now has more than 23,000 followers on Twitter.

I like to bring up Surfers against Sewage when people talk about sea blindness. In postindustrial societies, leisure and lifestyle activities assume some of the roles once occupied by vocations. The decline of fishing and merchant shipping as major employers in the UK doesn’t mean that the sea is “invisible” to Britons today.

It is not necessary for there to be a one-to-one relationship here, where every enthusiastic hobbyist also becomes a coastal activist or amateur data collector. Akkaynak has pointed out, for example, that if only one percent of divers uploaded their temperature readings to a website, that would immediately catapult Divers4Oceans into the first ranks of citizen science projects worldwide.

The idea of citizen scientists is gaining ground on many fronts. Another basic data point for measuring climate change on a grand scale is the density and distribution of phytoplankton. A very simple technology formalized in 1865 by the Vatican astronomer, Pietro Angelo Secchi, is still an effective method of tracking this. It’s a white disk that is lowered into the water; record the depth at which it is no longer visible, and you have measured the water clarity.[13]

Richard Kirby explains the citizen science potential here:

“Anyone who goes to sea can take part, whether you are a sailor with your own yacht, a crew-member, or are on a charter sailing holiday, or you are an angler, a diver or a fisherman. All you need is a Secchi Disk and the free Secchi app installed onto your smartphone or tablet.”

The app stores your GPS data until your device finds a network signal again. Don’t have a Secchi Disk around the house? It’s a simple DIY project.

“A Secchi disk can be made from any material, such as a white plastic bucket lid or a piece of plywood painted white. Offcuts of 3-5 mm white Foamex that you can often obtain from printers work very well. Attached to an inexpensive fibreglass tape measure with a weight hanging below, the Secchi Disk is lowered vertically into the seawater (you need to use sufficient weight to make the disk sink vertically, which will depend upon the disk material), and the Secchi Depth is noted. The quicker the Secchi Disk disappears from sight the smaller the Secchi Depth and the more phytoplankton there is in the water. Simple!”[14]

I hope a pattern is becoming evident. Indeed, journalists are beginning to take notice. In late 2015, the New York Times ran a whole story about recreational sailors coming to environmental activism directly because of their lived experience out on the open water.[15]

When you start adding up all of these different projects and groups, the numbers get very large. If participation in climate-change-related citizen science becomes part of the standard toolkit for beachgoers, boaters, surfers, and divers, this could move the needle on a number of issues where actual voting comes into play.

Conclusion

Much of what I’ve described in this three-part blog post may seem too incremental and tentative. Aren’t we in the midst of an unfolding global crisis? I’m as exasperated as the next person about the recalcitrance on the key environmental challenges, and the current fashion (in many different arenas) to dismiss expert opinion on crucial topics. But we’ve tried ringing the church bells and sending out the town criers for a generation now, and it isn’t working very well. Maybe the deep change in attitudes that is actually required needs time to take root. It’s not in the nature of deep change to come quickly. “They tell us that…” clearly does not resonate in the same way as “we have learned.” The new forms of sea visibility I’ve discussed here may be a path forward.

A more trenchant critique is that my “we” is too tilted toward the carbon-intensive, developed countries and overlooks the ways that a lot of people on the planet relate to the watery world. Ian Urbina’s “Outlaw Ocean” investigation drew attention to the fact that for a lot of people in the twenty-first century, getting out on the water is still bound up with themes familiar to labor historians, and even historians of slavery. I found this discussion of women’s work in the seafood industry even more eye-opening, in a way, than “Outlaw Ocean.” Dismissed by economists and government officials alike as “gleaners” or part-timers in shallow waters, it appears that women make up as much as half of the seafood workforce worldwide. They are not targeted for loans and government support, or studied systematically by development experts. Part of the “reason” given for this neglect was that the kind of seafood work that women were allowed to do was subsistence level (not commercial) or involved processing (such as the extraction of crab meat), among the lowest-paid of all labor.

By way of contrast, the activist group Sailors for the Sea was co-founded by a Rockefeller, and a similar group was co-founded by a Google executive and his wife.[16]

There’s a good historiographical reason, though, why I place so much emphasis on the ways that leisure activity, in particular, can morph into deeper engagement and more enlightened action.

In a now classic article that appeared in 2006, Michael Pearson offered this memorable image of the twenty-first century coast, from the vantage point of Goa, an old port on the Indian Ocean:

“A beach scene frequently found in Goa—and in other beach resorts on the west coast, such as Kovalam—is portly Western men in G-strings self-consciously helping traditional fishermen haul in their nets, which may contain enough for one meal. Their bikini-clad women enthusiastically take video pictures of this picturesque scene.”[17]

Pearson offered a bleak picture, although he qualified it slightly: “It is not a matter of the end of littoral society” but that “it has now been overwhelmed by forces from far inland and far away.”[18] The opposition of authentic littoral people (the traditional fishermen) and fake littoral people (here, the tourists) suggests that a vocational relationship to water is productive and profound, while a leisure relationship is parasitic. At the very least, it precludes an active, thoughtful engagement with the ocean. Playtime is, if not inherently destructive, then certainly frivolous.

The well-known historian David Abulafia strikes a similar note in The Great Sea, a sweeping treatment of the Mediterranean over the past several millennia.[19] His final chapter is entitled, evocatively, “The Last Mediterranean.” Reviewing the book in the International Journal of Maritime History, Colin Heywood remarked on the doom and gloom:

“[Mediterranean people are reduced to] purveying fish and chips to benighted package tourists… The last page of colour plates in the book sums it all up more graphically than mere words: two photographs… a sun-baked scene from hell at Lloret del Mar [a tourist-infested beach]… [and a] photograph of a small boat crammed to the gunwales with migrants from Africa, aground on the Spanish coast near the Straits of Gibraltar…”[20]

I worry about the lachrymose trope of “the Final Coast” in part because it is so memorable and easy to communicate. In the humanities, we have a soft spot for dystopian verdicts, and this one fills the bill.

The notion that people who don’t work on the water lack a tactile and direct relationship with it is, I think, a proposition that won’t stand up to close scrutiny. Instead, the place to begin is by stating that we live in an era of tremendous innovation in the ways that people relate to the coast, picture it, and think about it. There’s even a chance that the pace of this innovation will catch up to the rate at which our environmental and political challenges are growing.

My chapter on the twenty-first century coast would include the #beachclean crowds, the #plastictide tweeters, the indignant surfers, the thrill-seeking divers, the coast walkers, the beachcombing artists, and the self-appointed citizen scientists.

I hope I won’t see too many more concluding chapters about the dead coast, the last coast, and the fake coast. If we keep measuring coastal consciousness using the old yardsticks, we’ll miss where the action is in the twenty-first century.

Notes

[1] Jo Atherton, “The Message in 27,000 Pink Plastic Bottles,” http://www.plasticpollutioncoalition.org/pft/2016/1/11/the-message-in-27000-pink-plastic-bottles , accessed 7/23/16.

[2] Elizabeth Albert, “Silent Beaches,” in Steve Mentz, Oceanic New York (Brooklyn, Punctum, 2015), 1-13, quoted page 1.

[3] Albert, “Silent Beaches,” 1.

[4] David Jarratt, “Sense of place at a British coastal resort: Exploring ‘seasideness’ in Morecambe,” Tourism 63, no. 3 (2015), 351-363.

[5] Jarratt, “Sense of place,” 358.

[6] Jarratt, “Sense of place,” 355-357.

[7] http://mountaincoastriver.blogspot.co.uk/2016/06/the-frayed-atlantic-edge-learning-life.html , accessed 7/25/16.

[8] https://solwayshorewalker.wordpress.com/about/ , accessed 7/25/16.

[9] http://www.solwayshorestories.co.uk/shore-stories/the-re-shaping-of-the-firth/ , accessed 7/25/16.

[10] http://www.solwayshorestories.co.uk/shore-stories/the-shifting-solway-sands/ , accessed 7/25/16.

[11] http://www.whoi.edu/oceanus/feature/epiphany-among-the-manta-rays, accessed 7/26/16.

[12] https://www.sas.org.uk/history/ , accessed 7/26/16.

[13] I assume they don’t encourage this method near the mouths of rivers, where there would be plenty of suspended particles that aren’t necessarily plankton.

[14] http://blueplanetsociety.blogspot.co.uk/2016/04/studying-phytoplankton-with-citizen.html?m=1 , accessed 7/26/16.

[15] “In Pollution Fight, the Sailing World Has Just Scratched the Surface,” New York Times, December 24, 2015.

[16] As reported in the New York Times article of December 24, 2015, discussed above.

[17] Michael Pearson, “Littoral Society: The Concept and the Problems,” Journal of World History 17, no. 4 (2006), 353-373, quoted page 370.

[18] Pearson, “Littoral Society,” 373.

[19] David Abulafia, The Great Sea: A Human History of the Mediterranean (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2011).

[20] Colin Heywood, “The Great Sea,” International Journal of Maritime History 24, no. 2 (November 2012): 300-302. The photographs mentioned are Abulafia’s figures 74 and 75, facing Great Sea page 481.

#bluemind

Isaac,

Many thanks for your interesting post – seems like we are both stimulated by Jo Atherton’s prints: http://rwotton.blogspot.co.uk/2016/04/jo-athertons-anthropocene-prints.html

Best wishes,

Roger

Thank you, Roger! It’s wonderful how naturally interdisciplinary these themes are.