To kick off 2016 on the best possible note, here is the Coastal History blog’s fourth guest post, grounded firmly in the Southern Hemisphere.

To kick off 2016 on the best possible note, here is the Coastal History blog’s fourth guest post, grounded firmly in the Southern Hemisphere.

I was in Sydney for a conference a few years back and left very impressed with the nearly ubiquitous signposting and commemoration of the Aboriginal past (and present) in diverse and thought-provoking forms. There is really no comparison between the U.S. and Australia on this issue. On a recent trip to Washington, D.C. I made my way to the new National Museum of the American Indian, in large part because I was still trying to process what I had seen in Australia and imagine what that reckoning would look like in my own country.

Karin Speedy’s theme, the “blackbirding” trade in Pacific Islanders, falls into a somewhat different category; recognition has been perhaps slower and less forthcoming. The relative invisibility of this aspect of the colonial past recalls some of the problems I discussed in an earlier blog post, Maritime Heritage and Social Justice.

Previous guest posts have been by historians; Dr. Speedy is an Associate Professor and Head of French and Francophone Studies at Macquarie University in Sydney. I hope this will be the first of many guest posts by scholars from a variety of disciplines, particularly as the PTUC team takes the first steps toward establishing an interdisciplinary, international Coastal Studies journal.

–I.L.

Georges Baudoux’s Jean M’Baraï the Trepang Fisherman, is a masterful, ambiguous, semi-fictional novella that relates the brutal history of the Kanaka trade and highlights 19th century imperial connections between the French and British Pacific.[1] First published in 1919, based on the real lives of three métis or “half-castes” of the New Caledonian bush and on the oral histories of the author’s New Hebridean mining employees, themselves former Queensland Kanaka workers,[2] Georges Baudoux’s Jean M’Baraï the Trepang Fisherman describes a time when anglophone, francophone and Pacific peoples interacted, exchanged, and moved in and out of each other’s lives perhaps more frequently than today. The immense interest of this book for historians is its detailed account of all aspects of blackbirding in the Pacific, a history written on the basis of eye-witness accounts.

Georges Baudoux (1870-1949), New Caledonia’s first writer, arrived as a four year old in the French penal colony aboard the Virginie, a convict ship transporting prisoners from the Paris Commune. After a brief stint working for the local newspaper, at eighteen Baudoux became a man of the bush, eking out a living (like his protagonist Jean M’Baraï) as a trepang fisherman, then a stockman and miner. Making his fortune in mining, he purchased his own mines, employing both freed and runaway convicts, ex-sailors and drifters as well as Melanesians from the New Hebrides (Vanuatu). An astute observer and listener, Baudoux collected the stories of many of the characters he met in the bush, filing them away for use in the stories he would write in later life. He is celebrated in New Caledonia for the documentary quality of his texts and the “authenticity” in his reproduction of real-life characters, voices and events. His writings, while not untainted by paternalism and colonial stereotypes, are unusually subversive for the time in their unflinching critique of the destructive nature of the colonial project and their vision of a universal inhumanity that traverses all racial and linguistic boundaries.

I first came across Baudoux’s writing in 2003 when I was finishing my PhD and was asked if I could translate a passage in one of his stories that appeared to be written in Reunion Creole.[3] That fortuitous request led to a large research project investigating the little-known migration of Reunionese labourers to New Caledonia and their role in the development of a local creole language, Tayo.[4] With my background in colonial, Pacific and New Caledonian history, creole linguistics and postcolonial literature, it has been quite a thrill to bring all of these elements together in my translation of and critical introduction to Georges Baudoux’s Jean M’Baraï the Trepang Fisherman. This transnational New Caledonian blackbirding narrative gives anglophone readers the opportunity to read about a shameful and relatively unknown episode in Australian and Pacific history from an outsider’s (although close neighbour’s) perspective. As is made plain in the story, the transactions that took place between peoples in the frontier spaces and ports of New Caledonia, the New Hebrides and Queensland were not based on any notions of equality. Indeed, rooted in colonial power relations and concerned with monetary gain and exploitation, they were often extremely violent. While most people are aware of the “coolie trade”, the indenture system that replaced the slave trade and involved Indian and Chinese labourers, few people have heard about the Kanaka trade (Pacific labour trade/Pacific slave trade) that saw the displacement, abuse and deaths of many thousands of “blackbirds” across Oceania.

Blackbirding, the coercive recruitment of indentured Pacific Island workers through deception and/or violence, became widespread in the Pacific Ocean from the mid-19th century. While Europeans had been hiring Pacific Islanders from the late 18th century for whaling and in the sandalwood, bêche-de-mer and copra trades, this recruitment was not commodified until the development in the second half of the 19th century of the highly labour-intensive cotton and sugar industries.[5]

Aside from Ben Boyd’s disastrous attempt to introduce Pacific labourers into New South Wales in 1847,[6] the first organised blackbirding of Pacific Islanders was in 1857, when 65 Gilbert and Solomon Islanders were sold into indenture on Reunion Island.[7] From 1862-3, the notorious Peruvian Slave Trade saw Joseph Byrne’s ships plying the Pacific for human cargo,[8] and from 1863 to 1904 over 62,000 Kanakas from Vanuatu, the Solomon Islands, New Caledonia, the Gilbert Islands, Fiji and parts of Papua New Guinea were contracted to work on the Queensland sugar plantations.[9] Between 1865 and 1930, around 14,000 Melanesians (mostly New Hebrideans or ni-Vanuatu as they are known today) were imported into the French colony of New Caledonia to work, initially, on the sugar plantations and later in the mines.[10] Blackbirded labourers were also taken to work on the plantations of Fiji, Samoa and Tahiti and were used as pearl divers in the Torres Strait. French and English “recruiters” (or “slavers”) soon became fierce competitors (and sometime collaborators) in the Melanesian archipelagos.

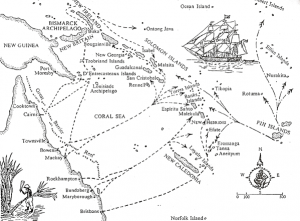

The Main Recruiting Routes: The Blackbirders, p. 3, Edward Wybergh Docker (courtesy of HarperCollins)

The real figures of those affected by the trade (those given above are based on contract numbers) are not known as many Islanders died, either murdered in blackbirding raids or as a result of shipboard violence or from disease in the insanitary hulls of the blackbirding ships before they entered into an indenture. The impact on the Island populations was huge. Over half of the adult male population of several islands of Vanuatu were working overseas at any one time during the labour trade and it is estimated that Vanuatu lost around 70 % of its people in the 19th century due to blackbirding and European disease.[11]

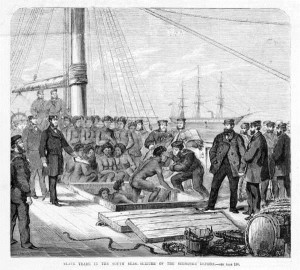

Kanakas destined for the Queensland sugar industry were usually signed up for three year contracts, a thumb print sufficing for agreement (whether or not the contract was understood). They were disembarked at numerous ports along the Queensland coast stretching from Brisbane in the south up to Cairns in the far north. Assigned a number and a European name, the Pacific Islanders were not allowed to mingle with white society, living in encampments on their employer’s property, and were required to work very long hours clearing the land and planting, cutting and preparing sugar cane for processing. Bound to their employer, their lives were highly regulated, they were often subject to mistreatment and overwork, they suffered high mortality rates and their meagre salary (£6 for the entire 3 years of labour – minus any fines that were owing) was only paid to them at the end of their contract (if they were lucky).

South Sea Islander labourers cutting sugar cane on a plantation at Bingera, Queensland, c. 1905, Image 171281, John Oxley Library, State Library of Queensland

There is a degree of discord between academic descriptions, oral histories and popular conceptions of the Pacific labour trade as a form of slavery. Academics are divided on the extent to which blackbirding was a feature of recruitment. In the late 1960s and 1970s the revisionist Canberra school eschewed notions of slavery in favour of emphasising the agency of the indentured workers.[12] Hunt and Kennedy[13] have noted a swing back in the popular media to reporting the entire period of this Pacific labour trade as being akin to slavery, a perspective from which the trade had been conceptualised from its beginnings.[14] This trend intensified in the lead-up to the 150 year anniversary of the trade in 2013 and there have been calls for apologies (as yet unanswered) from the Australian government for its role in the exploitation of the Kanaka workers. This view is also apparent in oral histories that have been recorded in resources such as the documentary film Sugar Slaves or dramatised as in Amie Batalibasi’s short film Blackbird.[15] These memorialising projects draw public attention to the horrors, injustices and racism suffered by the men, women and children taken from their island homes to work in the Queensland plantations. Whether or not blackbirding continued for the duration of the labour trade, there is agreement among academics and descendants of the workers that, at least in the early days, coercion was widespread. Tracey Banivanua-Mar has argued that throughout the trade “a lack of consent from individual Islanders rarely stood in the way of recruiters’ profits, and while not always overt and ever-present in labor recruiters’ behavior, violence and aggression continued to underpin the viability of colonial trades in the western Pacific”.[16]

While the majority of the Kanakas (a term that is nowadays a racist slur) were repatriated (many forcibly so, separated from wives and children once the White Australia policy came into effect after 1901), about 2000 stayed on in Australia.[17] Many of those who did manage to stay had found refuge in the Aboriginal community but subsequently suffered discrimination and lack of access to resources and it was not until 1994 that South Sea Islanders were formally recognised by the Commonwealth government as a “distinct disadvantaged group” who were to “be given access to health and welfare schemes similar to those for Aboriginals and Torres Strait Islanders”.[18] Over 20,000 of their descendants are living in Queensland today.

South Sea Islanders on a labour vessel, c.1900. Image 103470, John Oxley Library, State Library of Queensland

Criss-crossing the waters and ports of the Pacific, Georges Baudoux’s Jean M’Baraï the Trepang Fisherman thus offers a unique francophone window into historical debates on the nature of the Pacific labour trade. Historians will revel in the detailed descriptions of the recruitment of the Islander workers, conditions on board the recruiting ships, Anglo-French competition, tensions in the Pacific over the engagement of labourers, daily life in Queensland for both new recruits and “time expired” workers, and the repatriation of the labourers at the end of their indenture. Raw, brutal, and often confronting, it is a story that shares many parallels in language and practice with slavery and coolie narratives yet has its very own Oceanic particularities. The 19th century voice of Jean M’Baraï still resonates today as we reflect on the experiences and resilience of the Pacific South Sea Islanders who contributed to modern Australia: the many that left and the descendants of the few who stayed.

Georges Baudoux’s Jean M’Baraï the Trepang Fisherman is available as an Open Access free ebook and can be downloaded here: http://epress.lib.uts.edu.au/books/georges-baudouxs-jean-mbarai-trepang-fisherman

A print on demand option for those who prefer to turn real pages will be available shortly (details on the same web page).

Author Bio: Karin Speedy is an Associate Professor and Head of French and Francophone Studies at Macquarie University in Sydney, Australia. Her research focuses on historical, cultural, linguistic and literary links between peoples and communities of the Pacific and Indian Oceans, and in particular, interrogates the juncture between the colonial and postcolonial francophone and anglophone worlds.

Author Bio: Karin Speedy is an Associate Professor and Head of French and Francophone Studies at Macquarie University in Sydney, Australia. Her research focuses on historical, cultural, linguistic and literary links between peoples and communities of the Pacific and Indian Oceans, and in particular, interrogates the juncture between the colonial and postcolonial francophone and anglophone worlds.

She is on academia.edu: https://mq.academia.edu/KarinSpeedy and Twitter @KarinESpeedy

Notes

[1] Karin Speedy, Georges Baudoux’s Jean M’Baraï the trepang fisherman, (Sydney: UTS ePress, 2015).

[2] Kanaka is a Polynesian word that travelled around the Pacific with the whaling fleets. It means ‘human being” in Hawaiian but came to refer to the Melanesians/South Sea Islanders who were taken as labourers in Queensland.

[3] Karin Speedy, “Translating Socrates’ ‘Creole’ in Georges Baudoux’s Sauvages et Civilisés,” Metamorphoses. Special Issue on Francophone Literature, 11, no.1 (2003), 120-132.

[4] Karin Speedy, Colons, créoles et coolies: l’immigration réunionnaise en Nouvelle-Calédonie (XIXe siècle) et le tayo de Saint-Louis, (Paris: L’Harmattan, 2007).

[5] Dorothy Shineberg, They came for sandalwood: a study of the sandalwood trade in the south-west Pacific, 1830-1865, (London, New York: Melbourne University Press, Cambridge University Press, 1967).

[6] Marion Diamond, The Sea Horse and the Wanderer: Ben Boyd in Australia, (Melbourne: Melbourne University Press, 1988).

[7] Karin Speedy, “The Sutton case: the first Franco-Australian foray into blackbirding,” Journal of Pacific History, vol. 50, no. 3, (2015), 344-364. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/00223344.2015.1073868

[8] Henry Evans Maude, Slavers in Paradise. The Peruvian Slave Trade in Polynesia, 1862-1864, (Canberra: Australian National University Press, 1981).

[9] Doug Munro, “The labor trade in Melanesians to Queensland: an historiographic essay”, Journal of Social History, vol. 28, no. 3, (1995), 609-627.

[10] Dorothy Shineberg, “‘The New Hebridean is everywhere’: the Oceanian labor trade to New Caledonia, 1865-1930”, Pacific Studies, vol. 18, no. 2, (1995), 1-22.

[11] Alexandre François, “The dynamics of linguistic diversity: Egalitarian multilingualism and power imbalance among northern Vanuatu languages”, International Journal of the Sociology of Language, no. 214, (2012), 85–110.

[12] Clive Moore, “Revising the revisionists: the historiography of immigrant Melanesians in Australia”, Pacific Studies, vol.15, no.2, (1992), 61–86.

[13] Doug Hunt and K.H. Kennedy, “Bye bye blackbirder: the death of Ross Lewin”, Journal of the Royal Historical Society of Queensland, vol. 19. no.5, (2006), 805-823.

[14] Reid Mortensen, “Slaving in Australian courts: blackbirding cases, 1869-1871”, Journal of South Pacific Law no. 4 (2000), http://www.paclii.org/journals/fJSPL/vol04/7.shtml

[15] Sugar Slaves, (1995). A film made by Film Australia and the ABC, executive producer Sharon Connolly, director/co-producer Trevor Graham, producer, Penny Robins. Available on DVD. Blackbird had its first screenings in December 2015. See the Facebook page for the project here: https://www.facebook.com/blackbirdfilmproject Oral histories are also, of course, used in academic research.

[16] Tracey Banivanua-Mar, Violence and Colonial Dialogue: The Australian-Pacific Indentured Labor Trade. (Honolulu: University of Hawai’i Press, 2007).

[17] The Pacific Island Labourers Act of 1901 was one of a suite of laws passed from 1901 designed to exclude non-white workers and immigrants from staying in or entering Australia.

[18] Nic Maclellan, “South Sea Islanders unite in Australia”, Inside Story, 24 August 2012. http://insidestory.org.au/south-sea-islanders-unite-in-Australia

Comments are closed.