By now – after many years of work in the ‘Port Towns & Urban Cultures’ project – it’s probably old hat to say that port towns are important intersections between land and water, liminal zones and crossing points for people, goods and ideas. These transient places are of great interest to a range of historians, including those of mobility and transport. Docks and ports require a workforce, of course; some come and go, with the tides that bring the vessels in to harbour, but some stay, moving freight. So, historians of labour and historians of risk, accidents and safety might usefully explore dockside spaces to see what they reveal about work practices and occupational hazards, just as historians of port spaces might usefully explore the same spaces to see what they reveal about labour and risk around water.

Fleetwood Docks in Lancashire, 1910, nicely demonstrating some of the confusion of the dockside, along with some workers.

Courtesy National Railway Museum, 1997-7059_HOR_F_771.

Moving goods has long been hard work – for much of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries tending to be lowly thought of, sometimes lowly paid, and largely invisible beyond key labour disputes.[1] This relative obscurity is as true of ports as it is of the railways: docks were commercial, busy spaces, often closed off from the general public, and certainly not of interest to majority of people. Thinking about the day-to-day lives of the people who lived in port towns and worked in the docks is therefore a useful way to make connections between urban environments and waterside cultures.

Some historians have looked at occupational health and safety in royal and commercial dock spaces – Peter Bartrip, Richard Biddle, Adrian Jarvis and David Walker, for example.[2] An interesting example of the international nature of occupational mobility, and the impact this might have on the nature of port towns, is opened up by Merja-Liisa Hinkkanen’s work on disabled and ill Finnish seamen in British ports.[3] And there are as-yet largely unanswered questions about the impact of wider aspects upon dock workers’ bodies and lives, such as notions of masculinity.[4]

So why is this area of interest to the ‘Railway Work, Life & Death’ project, which I co-lead with colleagues at the National Railway Museum, and which focuses on railway worker accidents in the UK and Ireland? The railways, as one of the largest industries at the start of the 20th century, had extensive maritime interests, operating docks and vessels. So, plenty of railway employees worked aboard ships – and had accidents. This included, for example, Russel Wilfred Eley, who died on 10 November 1914 after falling down the hold of the Great Eastern Railway’s steamer Dresden whilst it was moored at Millwall Docks.

More ‘traditionally’, the railway companies’ lines criss-crossed docks throughout the UK and Ireland, exposing their employees and dock workers (amongst others) to dangers from moving trains – evocatively captured in Lionel Walden’s painting of Cardiff docks in 1894.

Our project uses accident reports produced by state-appointed inspectors to explore the nature of work and workplace accidents on the railways. At the moment we’ve focused on the years around the start of the First World War, but we’re currently extending this. We’ve been working with a team of volunteers at the National Railway Museum to make the accident reports and the information they contain more accessible – so far we’ve documented nearly 4,000 accidents, detailed in a free database accessible via our project website (www.railwayaccidents.port.ac.uk), along with a host of other resources which put railway work and staff accidents in context. This includes a weekly blog, exploring some of the cases and their implications in greater detail.

Like ports, work on occupational safety on the railways has (perhaps surprisingly!) been relatively limited, and has focused on those staff working in ‘classic’ railway roles – on the tracks, driving the trains, and so on.[5] But there’s clearly great potential to examine other roles, including where different dangers intersect – like at the water’s edge. So in this post I wanted to focus attention on the point at which railways & railway workplace dangers met shipping and shipping workplace dangers. In doing so I hoped to flag the potential that our project holds, not just for railway historians, but for historians of labour, social and cultural historians, and many more – including, of course, all those with interests in port towns.

A simple – very unscientific! – search of our database for locations involving the word ‘dock’ brings up 250 hits, a bit over 6% of the total cases in the database. Many of the cases are generic to railway work: dangers didn’t cease just because they were near water. However, the fact that vast quantities of goods and materials were being moved to and from ports meant that this was likely to be a busy environment, with trains constantly moving and peaks of fevered activity, all taking place at any time of day or night, whatever the weather – time and tide waits for no man, as they say. All of this magnified some of the dangers that the railway companies claimed were ‘inherent’ to railway work.

So, docksides saw plenty of shunting – the movement of wagons to assemble trains and get them running, and one of the more dangerous activities on the railways. In 1912, for example, 3 dock workers were injured at Middlesbrough Dock when a single shunt went wrong – something discussed in more detail here. Use of capstans to move wagons was also a frequent cause of some quite horrendous injuries and fatalities. It seems that however you tried to move wagons you were damned: casualties from horses, a major source of motive power around docks at the start of the 20th century, are also found littering our database.

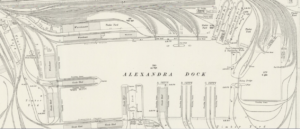

Just one example here. On 29 July 1912 crane-driver Joseph Saxton was at work on the Hull & Barnsley Railway, at Alexandra Dock, Hull. He was in charge of a 5-ton steam travelling crane, moving some large cast iron pipes a bit after 10pm. He lifted one of the pipes around two-and-a-half feet off the ground, when it fell and rolled over the edge of the quay into the dock. The crane also fell, so Saxton jumped, breaking his right leg. The case was one of the 3% of all railway workplace accidents that were investigated by state officials – in 1912 this amounted to 858 cases, of the 28,603 that year. As a result we have a reasonable degree of detail about Paxton’s accident – including that the pipe being lifted weighed over 4 tons, but the crane was set up to lift under 4 tons. There was also conflicting evidence about happened, leading Inspector JH Armytage to conclude that it was a combination of Saxton’s ‘careless manipulation of the brakes’ and incorrect information being passed between workers which caused the accident. All in all, then, it sounds like it could have a much worse outcome for Saxton.

So where does all this get us? This is obviously a very particular subset of port work and port workers, but it helps remind us about some of the (relatively) fixed points in what could be a transient community: the workforce. Without these people, the ports, docks and harbours – as well as their towns and associated communities – would not function. The detail from our project enables us to grasp these people (and what were often fundamental moments in their lives), going by the multitude of numbers and considering individual cases. As we extend the project – in terms of period covered (back into the 19th century and forward to 1939) and the types of documents included (company and trades union sources) – we will doubtless find plenty more cases relating to working life in port communities. In addition, there are vast bodies of material in archives relating directly to dock accidents, just waiting to be explored – something I’m keen to do, whether by applying similar methodologies to our project or through research collaboration and/or research students … just get in touch!

Mike Esbester is Senior Lecturer in History at the University of Portsmouth, and the academic lead on the ‘Railway Work, Life & Death’ project (www.railwayaccidents.port.ac.uk; @RWLDproject). His research focuses on cultures of safety, risk and accident prevention in modern Britain, and the history of transport and mobility. He is Deputy Editor of the Journal of Transport History; publications include The Birth of Modern Safety. Preventing Worker Accidents on Britain’s Railways, 1871-1948 (Taylor & Francis, forthcoming); with Paul Almond, Health and Safety in Contemporary Britain: Society, Legitimacy, and Change since 1960 (Palgrave, forthcoming 2019); and edited with Tom Crook, Governing Risks in Modern Britain: Danger, Safety and Accidents, c.1800-2000 (Palgrave, 2016).

[1] See, for example, J. Phillips, ‘Decasualisation and Disruption: industrial relations in the docks, 1945-1979’ in C. Wrigley (ed.), A History of British Industrial Relations, 1939-1979 (London, 1996): 165-85; J. Phillips, ‘Class and Industrial Relations in Britain: The ‘long’ mid-century and the case of port transport, c.1920-1970’, Twentieth Century British History 16 (2005): 52-73.

[2] P. Bartrip ‘“Enveloped in fog”: the asbestos problem in Britain’s Royal Naval Dockyards, 1949-1999’, International Journal of Maritime History, 26:4 (2014): 685- 701; R. Biddle, ‘Naval shipbuilding and the health of dockworkers c.1815-1871’, Family & Community History 12:2 (November 2009): 107-116; R. Biddle, ‘The Health of Workers in the Royal Dockyard, Portsmouth’ in R. Dunn and D. Leggett (eds), Re-Inventing the Ship (Aldershot, 2011): 93-112; A. Jarvis, ‘Safe Home in Port? Shipping Safety within the Port of Liverpool’, Northern Mariner 8:4 (October 1998): 17-33; D. Walker, ‘“Danger was something you were brought up wi’”: Workers’ Narratives on Occupational Health and Safety in the Workplace’, Scottish Labour History 46 (2011): 54-70, esp pp. 62-65.

Not strictly port related, but relevant nonetheless, is Richard Gorski’s work, including ‘Health and safety aboard British merchant ships: The case of first aid instruction, 1881-1908’ in R. Gorski (ed.), Maritime Labour. Contributions to the History of Work at Sea, 1500-2000 (Amsterdam, 2008): 155-83.

[3] Merja-Liisa Hinkkanen, ‘When the AB was able-bodied no longer: accidents and illnesses among Finnish sailors in British ports, 1882-1902’, International Journal of Maritime History, 8:1 (1996): 87-104.

[4] The work of Arthur McIvor and Ronnie Johnston is an excellent place to start on these issues in their wider occupational settings; see particularly ‘Dangerous work, hard men and broken bodies: masculinity in the Clydeside heavy industries, c.1930-1970s’, Labour History Review 69:2 (2004): 135-51.

[5] M. Esbester, ‘Organizing Work: Company Magazines and the Discipline of Safety’, Management and Organizational History 3:3-4 (August/ November 2008): 217-37; M. Esbester, The Birth of Modern Safety. Preventing Worker Accidents on Britain’s Railways, 1871-1948 (Taylor & Francis, forthcoming); A. Giles, ‘Railway Accidents and Nineteenth-Century Legislation: “Misconduct, Want of Caution or Causes Beyond their Control”?’, Labour History Review 76:2 (August 2011): 121-42; E. Knox, ‘Blood on the Tracks: Railway Employers and Safety in Late-Victorian and Edwardian Britain’, Historical Studies in Industrial Relations, 12 (Autumn 2001): 1-26.

Comments are closed.