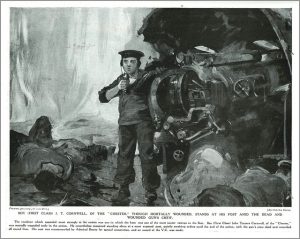

The exploits of Jack Cornwell at the battle of Jutland in 1916 offer a well-known story of gallantry in the face of adversity during the First World War. From humble origins, Cornwell joined the navy as a teenager and was stationed aboard HMS Chester at the Battle of Jutland.[1] Within the first hour of hostilities he was hit by shrapnel and, despite being mortally wounded, remained stationed at his post.[2] The ultimate sacrifice of Cornwell captured the public imagination during the challenging months of 1916. Among the many commemorations for Cornwell’s passing included a public funeral, a wax figure of the boy at Madame Tussauds, and the posthumous award of a Victoria Cross.[3] Significant credence was attributed to Cornwell’s time as a member of the Scouts in forming the character traits that led to his dutiful demise. During his formative years Cornwell was a member of St. Mary’s Mission Scouts at Manor Park until the troop disbanded in 1914.[4] The Chief Scout, Robert Baden-Powell, saw in Cornwell a sacrifice that would inspire other boys, with the creation of the ‘Cornwell Scout Badge’ awarded to boys who carried out acts of heroism.[5] There was, therefore, “perhaps no boy more famous, nor more extensively commemorated, during the First World War than John [Jack] Travers Cornwell”.[6]

The exploits of Jack Cornwell at the battle of Jutland in 1916 offer a well-known story of gallantry in the face of adversity during the First World War. From humble origins, Cornwell joined the navy as a teenager and was stationed aboard HMS Chester at the Battle of Jutland.[1] Within the first hour of hostilities he was hit by shrapnel and, despite being mortally wounded, remained stationed at his post.[2] The ultimate sacrifice of Cornwell captured the public imagination during the challenging months of 1916. Among the many commemorations for Cornwell’s passing included a public funeral, a wax figure of the boy at Madame Tussauds, and the posthumous award of a Victoria Cross.[3] Significant credence was attributed to Cornwell’s time as a member of the Scouts in forming the character traits that led to his dutiful demise. During his formative years Cornwell was a member of St. Mary’s Mission Scouts at Manor Park until the troop disbanded in 1914.[4] The Chief Scout, Robert Baden-Powell, saw in Cornwell a sacrifice that would inspire other boys, with the creation of the ‘Cornwell Scout Badge’ awarded to boys who carried out acts of heroism.[5] There was, therefore, “perhaps no boy more famous, nor more extensively commemorated, during the First World War than John [Jack] Travers Cornwell”.[6]

Compared to the story of Cornwell, the tale of another boy seaman at Jutland, William Walker, has been largely overlooked. The experience in the formative years of Walker – known to his peers as ‘Young Bill’ – are similar to those of Cornwell. Walker was from a humble background and joined the navy at a young age after spending time in a uniformed youth movement in the capital prior to the outbreak of war. Walker was a member of the 4th London Boys’ Brigade Company where he became adept at bugling.[7] It was not unusual for a member of the Boys’ Brigade in London to take up this instrument, with bugle bands the most common marching band in the pre-war years, and activities in the capital characterized by drill and martial music of the bugles.[8] Walker’s experiences in the 4th London Company stood him in good stead when he joined the navy where he became a bugler aboard HMS Calliope at the Battle of Jutland.[9]

Not only do parallels exist between their childhood experiences, but their exploits at Jutland bore several similarities. Both young seaman displayed unwavering obedience in the face of the hostilities of battle, embracing the traits of duty and discipline that were instilled in them as members of uniformed youth movements. Like Cornwell, Walker’s position was exposed during the battle. Walker was responsible for sounding ‘commence’ on board HMS Calliope and after this stood “bravely” – according to a report in the Boys’ Brigade Gazette – “by his Captain amidst the fury of the battle, while his ship played a gallant part in the great fight”.[10] Late in proceedings Walker was hit by a splinter of a shell, wounding him severely in his side.[11] Despite his injury, and echoing the experience of Cornwell, Walker stood faithfully at his post until fainting from a loss of blood.[12] Fortunately for Walker he recovered from his injuries which resulted in profound scarring and the removal of three ribs.[13] Whilst recuperating in hospital ‘Young Bill’ was visited by King George V who asked how “his brave little hero was feeling” and was later presented an inscribed bugle by the Admiral of the Fleet, Lord Jellicoe.[14] Despite his gallantry, the story of William Walker did not reach the same level of public attention as Cornwell, and in an article appearing in the Daily Sketch from October 1916, he was even described as “Another ‘Boy Cornwell’ in the Jutland Battle.”[15]

The experience of Walker is one that is illustrative of aspects of Boys’ Brigade life that defined the movement in the capital ideologically, through the notions of obedience and duty, and in the nature of its activities through the prevalence of bugling and drill. In Walker the Boys’ Brigade had their own hero of Jutland (akin to Cornwell for the Scouts) to be drawn upon as an example to promote the virtues of duty and discipline that were embraced during the war. In the Boys’ Brigade Gazette it was noted that:

“The conduct of Boy Walker should be made known to his comrades throughout the Brigade, and his gallant devotion to duty should be an example to us all”.[16]

However, the response of the Boys’ Brigade to ‘Young Bill’ was reserved when compared to the Scouts and their commemorations of Cornwell, where his exploits were utilized to invigorate the movement during the war. The response of the Brigade is indicative of an organization that was less confident in itself during the war than its Scouting brothers. This was, in part, due to the passing of the founder – William Alexander Smith – months before the outbreak of war and the uncertainties resulting from the prospect of accepting cadet recognition from the War Office.[17] Therefore, the experience of these boys in battle provides an insight into prevailing attitudes towards youth, the role of youth movements in wartime, and the masculine ideals of duty and discipline that were encompassed in the navy.

References

[1] Richard Davenport-Hines, “Cornwell, John Travers [Jack] 1900 – 1916”, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2004), online ed. [http://oxforddnb.com/view/article/45719, accessed 15 February 2016].

[2] Davenport-Hines “Cornwell”; Mary A. Conley, From Jack Tar to Union Jack. Representing Naval Manhood in the British Empire, 1870 – 1918, (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2009), 160.

[3] Conley, From Jack, 162.

[4] Davenport-Hines, “Cornwell”.

[5] Conley, From Jack, 171.

[6] Conley, From Jack, 162.

[7] “Boy William Walker”, The Boys’ Brigade Gazette, vol. 25, no. 3, November 1916, 29 – 30; 29.

[8] In the 1913-14 session two-thirds of all Boys’ Brigade bands were formed of bugles. See Anon, Banging the Drum. The Story of Boys’ Brigade Bands, (London: Boys’ Brigade, 1980). For an assessment of the situation in Glasgow see Chris Spackman, “Port Town Pipers of the Glasgow Battalion”, Port Towns & Urban Cultures Website, last accessed 18 February 2016, porttowns.port.ac.uk/port-town-pipers.

[9] Donald M. McFarlan, First For Boys. The Story of The Boys’ Brigade 1883 – 1983, (London: Collins, 1982), 50.

[10] “Boy William”, 30.

[11] McFarlan, First For Boys, 50.

[12] McFarlan, First For Boys, 50.

[13] “Boy William”, 30.

[14] “Boy William”, 30; McFarlan, First For Boys, 50.

[15] “Another ‘Boy Cornwell’ in the Jutland Battle”, Daily Sketch, 18 October 1916.

[16] “Boy William”, 30.

[17] Rosie Kennedy, The Children’s War. Britain, 1914 – 1918, (Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2014), 106 – 107; John Springhall, Brian Fraser, and Michael Hoare, Sure and Steadfast. A History of The Boys’ Brigade. 1883 – 1983, (London: Collins, 1983), 115 – 116; Roger S. Peacock, Pioneer of Boyhood. Story of Sir William A. Smith, Founder of the Boys’ Brigade, (London: Boys’ Brigade, 1954), 126.

This is the fitting blog for anybody who wants to search out out about this topic. You understand so much its nearly arduous to argue with you (not that I really would need…HaHa). You undoubtedly put a new spin on a subject thats been written about for years. Nice stuff, just nice!

Hello Wilette,

Thank you for your very kind words.

best

Chris

Hi Chris just let you know that William Robert walker was my great uncle