I’m writing today in response to Glen O’Hara’s recent blog post, “What about the Silence in the Archive?” Glen visited the National Archives of the United States in search of American commentary on British water policy. The short version is that he discovered U.S. bureaucrats had a lot to say on everyone’s water policy (the U.S.S.R.’s, that of countries in the developing world) with the exception of Britain. This, he remarks, is an unheralded but fundamental part of being a working historian. There’s no guarantee that what we plan to find will, indeed, present itself.

I’m writing today in response to Glen O’Hara’s recent blog post, “What about the Silence in the Archive?” Glen visited the National Archives of the United States in search of American commentary on British water policy. The short version is that he discovered U.S. bureaucrats had a lot to say on everyone’s water policy (the U.S.S.R.’s, that of countries in the developing world) with the exception of Britain. This, he remarks, is an unheralded but fundamental part of being a working historian. There’s no guarantee that what we plan to find will, indeed, present itself.

Reading his blog post made me think about the opposite problem. If not-finding is a challenge, so is finding. Glen’s own narrative contains some great examples of this. Maybe the lesson of his U.S. trip is that he should drop his old project and start writing about “American policymakers’ (mistaken) belief that the Soviet state was powerful enough to prevent widespread pollution.” But, of course, that wasn’t the plan. At a more general level, it’s tough when you find a good thing of the “wrong” or unanticipated variety. Timing is important, too. The right archival snippet or spot-on citation can come as a revelation if it presents itself at the beginning of a project; that same puzzle piece, arriving too late, can feel like a missed opportunity if you’ve already published the article where it would have belonged.

You can guess that I’ve got an example in mind. Late last year, I was in Chicago on a fine Fall weekend for the Midwest Conference on British Studies. One of the presenters was Scott Hughes Myerly, author of a book that I’d read and liked: British Military Spectacle from the Napoleonic Wars through the Crimea. [1] (To give you an idea of Myerly’s range, the last two chapters of this book are “Civil Disorder” and “Entertainment, Power, and Paradigm.”) He has a sensitive eye for the history of clothing and military uniforms, but places them in a much larger context. I had a chance to catch his ear between sessions, so I introduced myself and we wound up talking through the better part of the next panel, oblivious to the fact that the reception area was now completely deserted.

I explained a little about my work and what I thought was going on with sailors and their improvised outfits that they would flaunt on shore. I also mentioned sailors’ role in the London theater scene as vocal, and critical, members of the audience. He immediately grasped what I was doing and brought up a passage from Harriette Wilson’s memoirs in which catcalling sailors in a theater derided some dress uniforms that were not to their liking. He actually cited a page number from memory, 399, which I jotted down in my smart phone.

Here’s where my story gets a bit improbable. He’d just been up at a used bookstore on Chicago’s north side called The Armadillo’s Pillow and had spotted a copy of Wilson’s memoirs on the shelf. I dutifully noted down this information and after the conference, I looked up the address and plugged it into my GPS. With some effort, I managed to find a parking space in that neighborhood within walking distance of the bookstore.

He got the page number right, which leaves me wondering what it’s like to be Scott Hughes Myerly and have the equivalent of a vast searchable database ready for immediate and accurate retrieval out of one’s own head, for the purposes of offhand conversation.

So what about Harriette Wilson? Her occupation is given in the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography as “courtesan.” The memoirs I purchased were those that elicited the famous retort from the Duke of Wellington, “publish and be damned.” [2]

Here’s the passage that reminded Scott of my work:

After our sumptuous dinner, Lord Arthur proposed our driving over to Portsmouth, to see the play.

We went accordingly, and having hired a large stage-box, and seated ourselves in due form, all the sailors in the gallery began hissing and pelting us with oranges, and made such an astounding noise that, out of compassion for ourselves, as well as the rest of the audience, we were obliged to leave the theatre before the first act was over, and we were followed by a whole gang of tars, on our way to the inn. They called us Mounseers—German moustache rascals, and bl—dy Frenchmen.

I do not know whether the sailors objected to the dress of dragoons in general, as being a German costume, or whether it was our French Duc de Guiche who had caused all the mischief. However that may be, His Grace of Beaufort having got hold of the story from the newspapers probably, declared, with his usual liberality towards me, that the English tars at Portsmouth could not endure the idea of my not being legally married to Worcester; want of chastity being held in utter abhorrence among the crews of our Royal Navy, as a sin they have no idea of, and one which is never, by any chance, practised by them. [3]

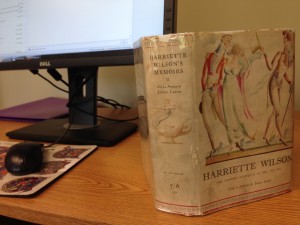

So this is one way that research “happens.” My edition of Wilson’s memoirs even comes with an illustration on the spine of the dust jacket showing a Regency courtesan emerging, diaphanous and genie-like, out of an Aladdin’s lamp, as if to remind me of the fairy-tale narrative of the book’s acquisition. I don’t mean to overstate our reliance on such lucky encounters, particularly in this digital age; try typing the phrase “sailors in the gallery” into Google Books and you will get several quite relevant passages from the correct time period, although not the one from Harriette Wilson.

The paradox of serendipity in research is that it mocks our pretensions to method. We can’t very well control when these handy citations, or helpful colleagues, come our way. In my case, I was already published and tenured when Wilson’s memoirs fell into my hands. Worse, I facilitated or enabled my own good luck by having an articulate story to tell a stranger about who I was and what I was looking for—exactly the things that a young scholar (who needs help the most) lacks. In a very real sense, I was able to elicit the Harriette Wilson citation because I had finished that project.

How should beginners anticipate and take advantage of the inherently unpredictable? I can share one suggestion. In retrospect, I made a strategic error when researching and writing my dissertation: I used my chapter outline from the dissertation proposal as a way to organize my research agenda and even the way I took notes (I had a file for “Chapter 2 materials,” and so on). I felt almost contractually obligated to stick to what my committee had approved. Consider, though, all the possibilities I shut out: for evidence and themes that didn’t fit into that framework, for chapters that belonged in the dissertation but hadn’t been anticipated by me in Ann Arbor, Michigan, and so forth. Researchers need structure, but they also must never lose their capacity to be surprised by what they find, or to allow serendipity to make its happy interventions.

Notes

[1] Scott Hughes Myerly, British Military Spectacle from the Napoleonic Wars through the Crimea (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1996).

[2] K. D. Reynolds, ‘Wilson, Harriette (1786–1845)’, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, 2004; online edn, Sept 2010 [http://www.oxforddnb.com/view/article/29653, accessed 3 May 2014]

[3] Harriette Wilson, Harriette Wilson’s Memoirs of Herself and Others (London: Peter Davies, 1929), 399-400. This work first appeared in 1825.

Comments are closed.