Department of Historical Studies, Gothenburg University, Sweden, 9th September 2014

Department of Historical Studies, Gothenburg University, Sweden, 9th September 2014

A recent workshop by the Universities of Gothenburg and Portsmouth brought together academics, archivists and heritage professionals to discuss the methodologies, data and potential beneficiaries of mapping port towns.

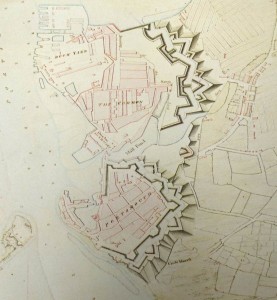

Dr Tomas Nilson and Dr Brad Beaven opened proceedings and explained that the history of port cities has usually been explored for its trading routes, commerce and strategic military significance. They argued that the port’s relative isolation from its civic hinterland and its capacity for cultural exchange through the influx of seafarers has largely been overlooked. The workshop aimed to capture some of these themes through discussing how mapping of issues such as work, leisure, crime and vice could form a ‘maritime geography’ of the port city.

A key aim of the workshop was to explore how this mapped data could be disseminated and engaged with beyond the academic community.

Beaven and Nilson’s papers demonstrated that while there were important similarities between merchant and naval sailortowns, there were striking differences in the character of ‘sailortown’ in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Beaven noted that the anticipation and the docking of a naval ship fostered a carnivalesque spectacle that appropriated the whole town. Focusing on drunkenness in port, Nilson noted that in merchant ports there was a relatively consistent set of weekly crime figures and these would be explored further and correlated with ships docking in the harbour.

Daniel Sjögren of the ‘Maritime Archives at the Regional State Archives of Gothenburg, explored the wide-ranging material held and how it could be utilised for mapping demographic, housing, drink, prostitution and work patterns. In a wide ranging discussion it was noted how these sources and themes corresponded well with their British equivalents. For example, at the same time as naval and garrison towns in Britain began imposing the Contagious Diseases Act, the Swedish port police were implementing similar controls on women.

Karl Bell and Robert James’ papers explored how mapping could locate people and places in their temporal-spatial contexts. James mapped cinemas that were near to naval bases and found that, not only did sailors appropriate these venues, they also significantly influenced the content of the entertainment. Bell argued that mapping contemporaries’ spectral sightings throws light upon an urban culture that did not fit well with the civic elites’ and Admiralty’s dominant narrative of modernity and progress. He examined the role of ghosts in mapping and reinforcing a sense of localised spatial identities, and articulating a supernatural urban typography. He also explored the ways in which Portsmouth’s ghost stories both aligned with and subverted ‘official’ memories of the town’s maritime past.

Karl Bell and Robert James’ papers explored how mapping could locate people and places in their temporal-spatial contexts. James mapped cinemas that were near to naval bases and found that, not only did sailors appropriate these venues, they also significantly influenced the content of the entertainment. Bell argued that mapping contemporaries’ spectral sightings throws light upon an urban culture that did not fit well with the civic elites’ and Admiralty’s dominant narrative of modernity and progress. He examined the role of ghosts in mapping and reinforcing a sense of localised spatial identities, and articulating a supernatural urban typography. He also explored the ways in which Portsmouth’s ghost stories both aligned with and subverted ‘official’ memories of the town’s maritime past.

Academics’ neglect of the socio-cultural history of the port town has been mirrored by Maritime Museums in Sweden, argued Cilla Ingvarsson. In her paper ‘How to make Maritime History come alive – a city walk perspective’, she explained that Swedish maritime Museums traditionally focused on the sea and miss the importance of the port as a unique maritime and urban space. Ingvarsson explained that through public engagement schemes such as free walking tours around the city, Gothenburg’s Sjöfarts Museet places the port and its people at the heart of the maritime/urban narrative. Discussion moved on to how the mapping project of Gothenburg could potentially enhance walking tours, through creating phone apps with added history, pictures and sound. Significantly, it would also extend the reach and diversity of the walk by providing walkers with a choice of languages to navigate the user – an idea very much welcomed by the Museum Director Björn Varenius

In the plenary session, delegates welcomed the collaboration between Gothenburg and Portsmouth. The papers and discussion had revealed that Gothenburg, London and Portsmouth had clear connections and contrasts and that a comparative study would shed light on a number issues such as:

In the plenary session, delegates welcomed the collaboration between Gothenburg and Portsmouth. The papers and discussion had revealed that Gothenburg, London and Portsmouth had clear connections and contrasts and that a comparative study would shed light on a number issues such as:

What were the key contrasts between merchant and naval ports and how did this influence their ‘sailortown’ cultures?

- how far did maritime culture on land facilitate a shared heritage in regards to leisure, food, drink, language, literature, song and folklore or were there distinct differences in the three ports?

- were there generic political factors that shaped the development and location of sailortown?

- was sailortown a homogeneous space or one of diversity? Did certain neighbourhoods of sailortowns establish specific national identities and cultures?

It was agreed that by using cartographic maps, information systems and historical sources both ‘real’ and ‘imagined’ facets of port-cities could be mapped and explored. In addition, researchers on the project will establish a common research methodology through creating a generic data base that will coordinate evidence to explore a set of agreed themes across the three ports.

Comments are closed.