The Battle of Jutland

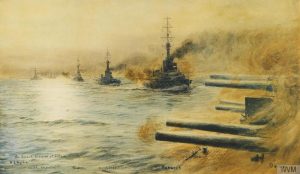

The largest naval battle of the First World War was fought in the North Sea near Jutland, Denmark, between 31 May and 1 June 1916. Over 100,000 sailors were aboard 250 warships and it was the only full-scale encounter between steel battleships during the War.

This naval battle was unlike any naval battle before or since. These were the largest battleships that had ever engaged in combat. Shells flew at enormous speeds and could penetrate a ship’s 11 inch steel armour. Sailors experienced terrifying conditions as explosions caused the scattering of red hot metal splinters, fire, choking fumes and deafening noise.

The battle lasted for just 36 hours and in that time 25 ships were sunk and over 8,000 men had perished. The British Grand Fleet suffered losses of 6,094 compared to 2,551 Germans killed.

Breaking the News

On 3 June 1916 the Admiralty announced that the Royal Navy had fought a battle off the Jutland coast. First Lord of the Admiralty, Arthur Balfour, who reportedly wrote:

The battle cruisers Queen Mary, Indefatigable, Invincible, and the cruisers Defence and Black Prince were sunk. The Warrior was disabled, and after being towed for some time had to be abandoned by her crew. It is also known that the destroyers Tipperary, Turbulent, Fortune, Sparrowhawk and Ardent were lost, and six others are not yet accounted for…

Only at the end of the report did it declare that ‘the enemy’s losses were serious.’ However, such was the limited intelligence immediately after the battle, the Admiralty was unable to convey detailed figures of German losses. This only added to the press and public’s perception that Britain had actually lost the battle. The popular newspaper the Daily News was responded to the Admiralty’s communique ‘as the greatest disaster to the British arms.’

The Anxious Wait for News

Front page of the Daily Sketch, 21 June 1916. By kind permission of the National Museum of the Royal Navy.

The Admiralty were unable to produce accurate casualty lists and families faced a confusing and anxious time. Relatives in towns with significant sailor populations gathered around newspaper offices for information. This very public expression of shock and grief was captured by the Portsmouth Evening News as it was reported that:

Two women in Commercial-road were seen to fall in a faint upon reading the news of the losses sustained, and through-out the night the sorrow and anxiety in innumerable homes were tragic. Naval men assembled in little knots in the principal thoroughfares, discussing the news available and the possibilities of what actually happened.

A British Victory?

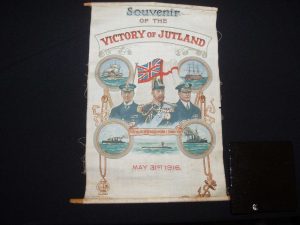

Battle of Jutland victory scroll, c.1916. © The Great War Archive, University of Oxford http://www.oucs.ox.ac.uk

After the gloomy initial reports news started to filter in that the Battle was a win for Britain. Experts calculated that, although Britain had lost more ships and men, the German High Seas Fleet had been irreparably damaged.

Local newspapers began profiling the ‘heroes of Jutland’ who had local connections. These profiles, which fused local pride with the national cause, recast the Jutland Battle into a heroic victory. Significantly, as much space was devoted to missing stokers as there was to officers, which conveyed the message that all social classes in local communities had been affected by the Battle.

Understanding the Impact of Jutland

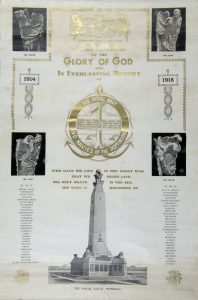

Memorial scroll for Able Seaman Thomas Slade. By kind permission of the National Museum of the Royal Navy.

This battle had a significant impact on families in urban and rural communities in Britain. However, towns with seafaring populations were disproportionately hit.

The Naval towns of Portsmouth and Gosport lost over 660 men while Plymouth, Stonehouse and Devonport suffered over 300 losses. Regions which had merchant ports such as Liverpool, London and Glasgow also recorded substantial casualties. The table below shows figures for casualties whose families were based in other large towns and cities:

| City/Town | Number (based on Next of Kin address) |

| Liverpool | 173 |

| Glasgow | 96 |

| Bristol | 94 |

| Southampton | 85 |

| Manchester | 73 |

| Birmingham | 68 |

| Belfast | 60 |

| Sheffield | 57 |

| Leeds | 56 |

| Newcastle | 50 |

| Dublin | 49 |

| Hull | 44 |

| Cardiff | 38 |

| Brighton | 38 |

| Edinburgh | 37 |

| Bradford | 33 |

| Nottingham | 31 |

| Reading | 31 |

| Hartlepool | 30 |

In 1924 the Imperial War Graves Commission erected monuments in the home ports of Plymouth, Chatham and Portsmouth as a tribute to sailors who had lost their lives at sea and had no known grave. Portsmouth’s memorial included the names of nearly 10,000 sailors. Over half of those killed at Jutland are named there.

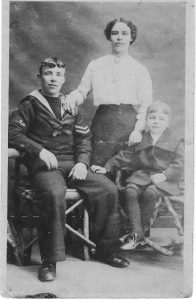

William John Hutchings with his wife Lillian and son William, c. 1914. By kind permission of the Dawlish World War One Project, www.dawlishww1.org.uk

Click to find out more about our research and access the Battle of Jutland Casualty Database

Research and text created by Professor Brad Beaven and Dr Melanie Bassett for an AHRC Gateways to the First World War funded-project.

Comments are closed.