When nineteenth-century Britons stood facing the ocean, what did they think about?

When nineteenth-century Britons stood facing the ocean, what did they think about?

Did they rejoice in the healthy sea breezes? Fret about a French invasion? Did they daydream about travel, worry about stock market crashes, plot the conversion of unbelievers in far-flung colonies? Or, watching the waves themselves, did they marvel at the scientific achievement represented by the compilation of precise tide tables for the entire planet? [1]

Or did they think about this: What will happen to the ocean at the end of time?

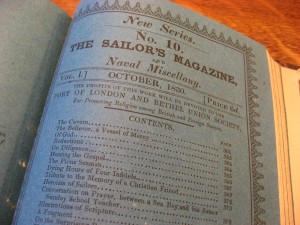

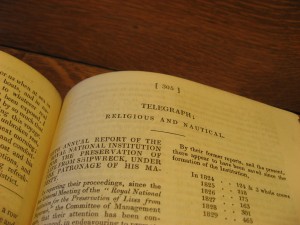

Last week, I spent an afternoon with the 1830 volume of the Sailor’s Magazine, an evangelical publication put out in London. It was the voice of the Bethel missionary movement, which sought to bring the gospel to seafarers. [2] They serialized a remarkable essay by Rev. W.B. Wiliams—whose unwieldy title was “The sea considered as existent, and finally to be extinct.” It was so long that it had to appear in two parts. Thanks to digital photography, I was able to postpone a thorough reading until my short research trip was over.

“… the ocean has a surface of 85 millions of miles square,” Williams explains, yet in Revelations 21:1, it states “And there was no more sea.” [3] Is this a literal or figurative statement? “Commentators are much divided as to the import of these words.” [4] Scripture seems to associate the sea with wickedness and obscurity; the Beast will arise from the sea. Then, of course, there is the new sea that will, according to Revelations 15:2, replace the old, troubled one: “And I saw them that had gotten the victory over the Beast… stand on a sea of glass, having the harps of God, and they sing the song of Moses and the Lamb!” [5]

This may seem a bit “out there,” but Williams also had a gift for homely and accessible metaphors. If the tumultuous sea were removed, we could have access to things that are now hidden. Each recession of the tide reveals this in a small way. We can “walk on hitherto untrodden ground, and we safely tread, fearlessly collect materials, and directly judge of facts unattainable before…” [6] If you are troubled by the mysterious ways of Providence, walk down to the beach at low tide for a taste of how you will, one day, understand even what has brought you grief and frustration in this life.

Is it all humbug? Was this material included as filler? It’s possible. And it is difficult to know the scale of the readership. The rarity of this periodical today hints that it may have been little circulated, and little loved. The evidence certainly suggests that the Sailor’s Magazine was mostly about what sailors ought to become, and not much about who they were.

Does that, then, imply that the correct thing to do with Williams’ sermon is to simply ignore it? In today’s academic world, there’s not a lot of time for reading without an agenda. With an eye on the clock, we look for what we expect or “need” to find—perhaps here, for accounts of the temperance movement, for anecdotes about crimps and sailortown landlords, for those rare instances of sailors’ struggles to find their own voice. We look for pieces of evidence that might command the respect of a busy journal editor or a distracted peer reviewer. It’s tempting, and maybe even smart, to read Sailor’s Magazine and skip the preachy bits.

Does that, then, imply that the correct thing to do with Williams’ sermon is to simply ignore it? In today’s academic world, there’s not a lot of time for reading without an agenda. With an eye on the clock, we look for what we expect or “need” to find—perhaps here, for accounts of the temperance movement, for anecdotes about crimps and sailortown landlords, for those rare instances of sailors’ struggles to find their own voice. We look for pieces of evidence that might command the respect of a busy journal editor or a distracted peer reviewer. It’s tempting, and maybe even smart, to read Sailor’s Magazine and skip the preachy bits.

We may have something in common with the sailors of yesteryear; we don’t have a great appetite for long, elaborate, footnoted sermons. Yet the Sailor’s Magazine does offer a window into a Christian sensibility that would, in fact, have resonated in more subtle ways with ordinary seafaring men. Some of the material had roots in a quite ancient tradition of memento mori and devotional literature. Consider this short poem, whose second stanza turns the gaze sternly back upon the viewer:

A THOUGHT ON THE SEA-SHORE.

In ev’ry object here, I see

Something, O Lord, that leads to thee

Firm as the rocks thy promise stands,

Thy mercies countless as the sands,

Thy love a sea immensely wide,

Thy grace an ever-flowing tide.

In ev’ry object here, I see

Something, my heart, that points at thee:

Hard as the rocks that point the strand,

Unfruitful as the barren sand,

Deep and deceitful as the ocean,

And, like the tides, in constant motion. [7]

Just as tastemakers codified definitions of “the beautiful” and “the sublime,” these kinds of meditations are a form of training in how to look, how to think, and how to feel. I know I’ll think about these passages next time I stand on a beach. And I’m far less primed and culturally receptive than the original readership of the Sailor’s Magazine.

When sailors looked out at the water, did they sometimes think about the grand sweep of sacred history, the world’s beginning and its end? When they watched waves crashing on the shore, did they sometimes feel the pangs of a troubled conscience? I suspect they did.

Notes

[1] Michael Reidy, Tides of History: Ocean Science and Her Majesty’s Navy (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2008).

[2] The standard work on the Bethel movement is Roald Kverndal, Seamen’s Missions: Their Origin and Early Growth (Pasadena, CA: William Carey Library, 1986).

[3] Sailor’s Magazine (London) New Series 1, no. 2 (February 1830), page 41. (Hereafter SM.)

[4] SM 1, no. 2, page 43

[5] SM 1, no. 2, page 46

[6] SM 1, no. 2, page 44

[7] SM 1, no. 8 (August 1830), page 289. Apparently these lines are attributed to Rev. John Newton, the author of “Amazing Grace.”

Comments are closed.