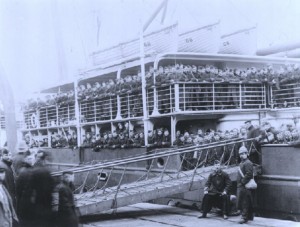

Troop embarkation onto SS Majestic at Southampton dock, either December 1899 or February 1900. Image attributed to http://www.titanic-titanic.com

The provincial press of the late nineteenth-century provides a fascinating insight into how imperialistic sentiment was conveyed to a newly literate working-class.[1] The provincial press adopted the conventions of ‘new journalism’, catering for working-class tastes by prioritising the reporting of sport, sensationalist news and by placing a focus upon localised issues.[2] Its rise paralleled the growth of civic identity and a drive by the civic elite to foster links with national and imperial narratives.[3] It is pertinent to assert that by linking local news with imperial interests, the working classes felt more of a connection with ‘empire’ through a local focus. By analysing two provincial press case studies, this article will argue that the provincial press in Liverpool and Southampton actively mirrored the localised enthusiasm for ‘empire’ by emphasising and highlighting local imperial qualities indicative to the town in question.[4]

Brad Beaven has stated that a town’s receptiveness to imperialist sentiment can largely be attributed to the specific social milieu of that town.[5] For example, Beaven highlights how Portsmouth and Coventry primarily embraced ‘empire’ respectively through celebration of their militaristic and industrial identities.[6] This trend continues through the pages of the provincial press case studies, whereby the ports of Liverpool and Southampton acted as both embarkation and disembarkation points for Boer War troops. In both locations well-wishers gathered in their thousands to ‘send off’ and welcome home imperial troops, cheering from the quay and displaying items of patriotism such as Union flags.[7]

In one instance, during the homecoming of the City Imperial Volunteers (C.I.V.) into Southampton, tickets to the disembarkation point had to be issued by the civic authorities in order to control the vastly gathered crowd.[8] Scenes of celebration were not simply reserved for British troops, as indicated by a report in the Liverpool Mercury that detailed the highly enthusiastic send off for Canadian volunteers, with the Mayor of Liverpool proclaiming them to be ‘gallant citizen soldiers’.[9] It is fair to hypothesise in this instance that the celebrations seen at the embarkation and homecoming of troops is highly indicative of the perceived role of the port town, in that it functioned as a gateway to the imperial war.

Both case studies also exhibit pertinent examples of how the locality aided the imperial war through the use of the port. The Liverpool Mercury contained a ‘Troops and Transport’ section in every issue studied, proudly detailing every local embarkation and arrival for all troop and cargo shipping serving the war. Likewise, the Southampton-focused Hampshire Advertiser offered a similar section, although the regularity of publication was varied. The arrivals of dignitaries in port were also given considerable column inches, with the homecoming of General George White, a figure publicly glorified following his gallantry at the relief of Ladysmith, posing a particularly colourful example, whereby the crowds gathered in their thousands before breaking barriers to get a glimpse of the visitor.[10] The paper also proudly highlights how Southampton was the first to award Lord Roberts the freedom of the city.[11] Like General White, Lord Roberts had been the subject of intense valorisation by the press following his role in the capture of Pretoria. The decision by Southampton’s civic elite to award him the freedom of the city, and its enthusiastic reporting in the Hampshire Advertiser again illustrates how imperial issues only became relevant when they were given an intrinsically localised focus.

This article has demonstrated how using the provincial press to analyse the local response to imperial events can highlight how the port towns of Liverpool and Southampton readily embraced the influence of ‘empire’ through the celebration of troop movements and their geographical positions as imperial gateways. The topic would benefit from further research, complimenting the provincial press case studies with a variety of social sources, in order to fully appreciate the extent of popular imperialism within the port town setting.

References

[1]For an excellent introduction to the rise of ‘new journalism’ and the provincial press, see Caroline Sumpter, “The Cheap Press and the ‘Reading Crowd’,” Media History 12, 3 (2006): 240.

[2] James Curran, “Media and the Making of British Society, c.1700-2000,” Media History 8, 2 (2002): 141.

[3] Brad Beaven, Visions of empire, Patriotism, popular culture and the city, 1870-1939 (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2012), 37.

[4] Case studies comprise of the Hampshire Advertiser and the Liverpool Mercury. Each was sampled at fortnightly intervals beginning 10 January 1900 until the end of that year.

[5] Brad Beaven, “The Provincial Press, Civic Ceremony and the Citizen-Soldier during the Boer War, 1899-1902: A Study of Local Patriotism,” The Journal of Imperial and Commonwealth History 37, 2 (2009): 208-9.

[6] Beaven, “The Provincial Press,” 216-17.

[7] Examples found in Liverpool Mercury 24 January 1900, 21 February, 4 April, 18 April, 22 August, 12 December and Hampshire Advertiser 10 January 1900, 7 February, 21 March, 4 April, 18 April, 19 September, 31 October, 28 November.

[8] Hampshire Advertiser, 31 October 1900.

[9] Liverpool Mercury, 12 December 1900.

[10] Hampshire Advertiser, 18 April 1900.

[11] Hampshire Advertiser, 17 October 1900.

Comments are closed.