Today, I’m happy to introduce the Coastal History Blog’s second guest post, by Katy Roscoe. (The first guest post was by Julia Leikin.) Island studies have featured before in this blog, in “Are Islands Insular?” but also in “Offshore and Offshoring”. In today’s post, Roscoe explains how her work as part of the Carceral Archipelago project complicates our picture of how islands functioned. It has become increasingly clear that islands played a pivotal role in modern history, not only in their role as prisons but also as one of the most important sites of plantation labor (whether indentured or enslaved). I suspect that this reappraisal of the porous land-sea barrier has resonance beyond the study of island prisons. – I.L.

The transportation of convicts to Australia has long been associated with two distinct stages: the lengthy sea voyage across the Atlantic and Indian Oceans, followed by confrontation with the vast expanse of the Australian bush. Yet, for some convicts the experience of transportation centred on islands. My PhD research looks at a ‘chain’ of islands to which convicts were transported in the nineteenth century and asks: Did islands have a special role to play in the Australian convict system?

Imagined Islands

Island studies have been guilty of ignoring prison islands. In a quest to highlight the ‘connected’ nature of island spaces, nissologists write off islands that incarcerate people as clichéd. This is partly a reaction to a macabre fascination of the public with prison islands as the most isolated (and therefore) dreadful of all. It is perhaps not surprising that they loom large in our imagination as islands have been associated with isolation from society since the very first English novel: Robinson Crusoe.

Carceral Archipelago

Islands that incarcerated people were far from mere ‘symbolic’ imaginaries. They were historical realities – widespread across the globe and across history. Islands were the preferred site for leper colonies, quarantine stations, POW camps, mental asylums, vagrant depots, and, of course, prisons. However, even within the field of prison and convict studies, islands are rarely compared across national or global contexts. The University of Leicester’s Carceral Archipelago Project (of which my work is a part) aims to make comparisons and connections about convict transportation on a global scale. Though the project’s name comes from Foucault’s term for the rise of disciplinary institutions, we are fast discovering there was an actual archipelago of carceral islands that stretched across the globe. In our work we repeatedly encounter islands as sites of incarceration and maritime journeys as central to the organisation and experience of transportation as punishment.

Some members of the Carceral Archipelago team on a panel at ENIUGH conference. From left to right : Clare Anderson, Christian De Vito, Katy Roscoe, Takashi Miyamoto, Carrie Crockett.

Why islands?

Islands are ideally situated as convict destinations because they are extremely versatile spaces. On the one hand they are connected to maritime networks. This made them perfect for shipping goods harvested by convicts or for use as trading or ship refitting posts which convicts built. Sometimes convicts were transported to islands that acted as strategic bases from which to uphold territorial claims. On the other hand, islands are relatively inaccessible which was desirable from a penal perspective. With the sea as a natural barrier islands were harder to escape from. Islands were also thought to inspire a particular dread which acted as a deterrent to potential offenders.

Not such “natural prisons”?

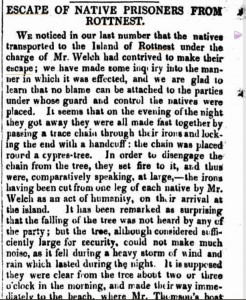

For all their reputation as ‘natural prisons,’ islands were far from inescapable. Though most islands had prison buildings, whilst labouring or roaming convicts were more likely to be unchained or undersupervised compared with the mainland. The sea was extremely porous with convicts swimming to shore from Cockatoo Island, escaping on unchained boats from Rottnest or even building one covertly on Melville. In one remarkable case two convicts took advantage of everyone searching the waters of Sydney harbour to hide for days in an underground crevice. Another issue with island prisons was that the water-land boundaries became sites of contested forms of security. One of Cockatoo’s resident military guards saw his responsibility pass over to the water police as soon as an escaping convict set foot in the water.

Rottnest’s convicts escape via boat (Perth Gazette, 1 Sept 1838 via Trove)

An “expensive incumbrance [sic]”

The maritime barrier may help keep convicts in some of the time, but it also made it more expensive to bring the convicts, staff and their families in. Most islands either relied on government ships or ‘shared’ with commercial carriers. The shipping of supplies of food or fresh water also rendered prison islands more costly than mainland prisons, particularly if they were far away. Melville Island was a six month journey from Sydney and supply ships were often lost thanks to bad weather, almost unnavigable straits, and piracy. The bounded nature of smaller islands meant they often could not provide food for themselves or goods for sale.

Too far from “the eye of authority”

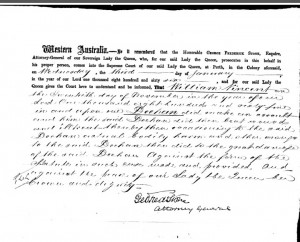

The price paid for inaccessibility to the island could be much higher, as key prison administrators were at a distance from the daily events on the island. In many cases, a lack of available boats and the vagaries of bad weather prevented visits that were urgently required from the Medical Officer. The extra hassle was also frequently used to justify infrequent inspections by the Visiting Magistrates who were supposed to guard against mismanagement. The inaccessibility of these islands to inspection by members of the general public made them particular areas of concern, appearing ‘unseeable’ and therefore dangerous. Rottnest was plagued by accusations of systematic neglect, cruelty and even torture. Even when staff tried to instil strict penal discipline, convicts on Melville bartered with resident sailors such that rum was in plentiful supply, resulting in drunkenness and malingering.

Supreme Court File for Superintendent of Rottnest (William Vincent) who was tried for assaulting Deehan, an aboriginal prisoner. State Record Office WA.

Prison islands were both connected and isolated spaces. This made them challenging as they were both too isolated to administer well and too connected to maritime spaces that offered opportunity for actual escape, or—in the form of rum—a virtual escape from the pains of imprisonment. This challenges the categorization of prison islands as uniformly isolated in island studies. It further suggests to scholars of convict studies that islands were unique within the wider convict system.

Katy Roscoe is a PhD candidate in History at the University of Leicester. Her research looks at what role Australian islands played as sites of convict transportation in the nineteenth century. She is part of the Carceral Archipelago project which analyses convict transportation on a global scale. For more on Katy’s research see her Academia.edu page or follow her on twitter @katwee_ . For blogs from all of the Carceral Archipelago team please visit: http://staffblogs.le.ac.uk/carchipelago/

Comments are closed.